It’s easy to get caught up in the nuts and bolts of studying music. Intervals, scales, chords, key signatures, chord progressions…once we dive into the deep pool of musical fundamentals, it can take some effort to recall that our ultimate objective is to create and play music.

Indeed, it’s important to remember that the study of music as a formal, institutional affair will always be a biased sort of learning—we may treat our scales and chords and other wonderful musical basics as gospel, but they are derived from a fairly specific musical tradition, and not every practitioner of music will see and study that tradition the same (or at all).

Some of the most remarkable musicians to ever walk the planet couldn’t tell you what a C-major scale is or how a cadence works. They might not even be able to give you any succinct practice pointers (or at least not any that will make sense to you). And yet, when you hear them play, there’s no doubt that they rank among the masters of their craft.

How is this possible?

It’s because they spend a lot of time with the music.

This explanation may seem a bit over-simplified, however, it really is all too common for us to neglect spending time learning from the music itself while we’re busy studying the elements that go into its construction.

The thing to always remember is this: We derive the elements of our musical study from the music.

We’ve spent lots of time throughout this article series focusing on those elements. We’ve learned how to build scales and chords, learned how to read key signatures, and learned how to analyze chord scales. We’ve looked at how different keys are related to one another, how to interpret non-scale tones, and how cadences work. We even spent an entire article talking about how awesome the minor scale is and why we need to pay a little extra attention to how it works when working with music that uses minor keys.

Now that we’ve got a solid grasp on the foundations of keys, it’s time to look at what we do with them, how we think about them, and how they can help us in our own musical studies.

To do this we’re going to look at three areas of historical and stylistic relevance for keys, talking all the while about how their key-based designs have affected our sense of how keys work today. Please note that these topics are hardly representative of all of the facets of keys and how they are used in music, but they will provide us with a good set of talking points to work with.

We will present our three sections as follows:

- How Beethoven Broke Everything: Here we will talk about one of the more underrated but prominent conventions of the Classical era, how it was Beethoven who ultimately broke that convention such that it could progress music into the musical eras to come, and how both the traditional convention and Beethoven’s innovations of it continue to influence how we perceive keys in the modern day.

- Jazz Cats Need Twelve Lives: In this section we will look at how keys are treated in the beginning stages of jazz study. We will look at several examples of standard jazz charts, talk about how key changes in jazz are treated differently than in classical music, and introduce how jazz treats the key-scale with regards to improvisation.

- Beautiful Noises: In our last section we’ll explore the movement away from the sound of keys by composers of the late 19th century, and how that shift continues to influence everything from modern classical music, to film music, pop, and beyond.

Throughout this article we will be referencing information we’ve covered in the previous articles of this series, so if you haven’t given them a look yet, now would be a great time to check them out!

If you have read the previous articles in this series and have succeeded in making it to this point, congratulations! We covered a lot throughout this series, and now it’s time to sit back and enjoy the view our study has afforded us. Let’s check out what our hard-earned knowledge of keys can show us!

How Beethoven Broke Everything: Conventional Wisdom

To start, let’s give a listen to the beginning of Haydn’s Sonata No. 10 in C Major:

No doubt we can all agree: it sounds very Haydn. Which is to say, it sounds like a prime example of keyboard music from the heart of the Classical Era of European classical music, which spanned the decades approximately between the death of J.S. Bach in 1750, and the death of Beethoven in 1827.

That we could probably identify this music as originating from that era with not much more than a cursory understanding of its technicalities is remarkable enough, but what’s perhaps more amazing is how music such as this, which comes from such a brief (albeit rich) period of musical history can still have such a lasting effect on the unbridled music of today’s world.

Particularly as pianists, almost all of the music we will use to learn with can be traced back to Classical music, and not simply because we are studying the instrument that was born in that era to play music from that era, but also because the sound of the music of that era has so thoroughly affected the trajectory of Western Art music that we cannot help but think that it sounds, well…right.

Rather than take time to look in detail at what all goes into that sound and what it is exactly that has settled into our collective musical psyche to influence how we perceive the “rightness” of that sound, let’s look at a couple of examples that will demonstrate the point more efficiently.

Below are two short snippets of music. One very casually uses some of the musical conventions we derive largely from the Classical Era, and the other decidedly does not. See if you can play them both slowly:

Obviously, one sounds much better than the other.

And yet, “better” in this case is a subjective qualification, or, in other words, an opinion we form built on nothing beyond our own sense of what sounds “good” and “bad” in music. Now, if you find yourself rolling your eyes a bit at this, that’s entirely reasonable. And to be sure, we, in fact, “measure,” or map-out, points in the “good” version that make it “good,” and points in the “bad” version that do the opposite.

As it happens however, the methods we would use to determine the quality of these examples are the same ones we use to recognize the sound of Classical music. This means that already, without even thinking of it, we’re geared to compare the sound of key-based music to something that adheres to certain Classical conventions.

“But wait,” you may be thinking, “how can there be so many different kinds of music that use keys that don’t sound like Classical music then?!”

Ding Ding Ding!!

That question strikes at the core of our concerns for this section. But rather than make the attempt to answer it outright, we’re going to focus on a small, but significant change to the conventions of musical thinking from that era that exemplifies both the rate and timbre of change that, centuries later, would allow use to hear Haydn on one station, and Van Halen on another.

The Dominant Dominant

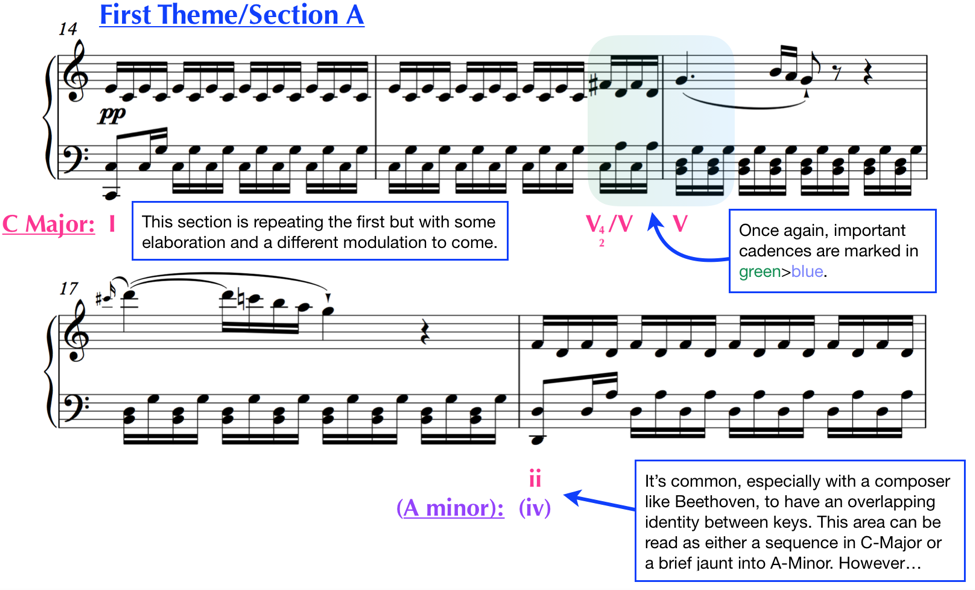

Let’s look at that Haydn sonata again, this time with some light analysis:

As with most of the sonatas composed during this era, this sonata is written in sonata form.

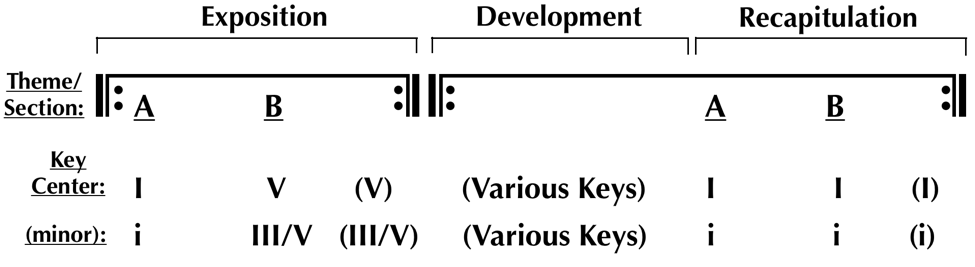

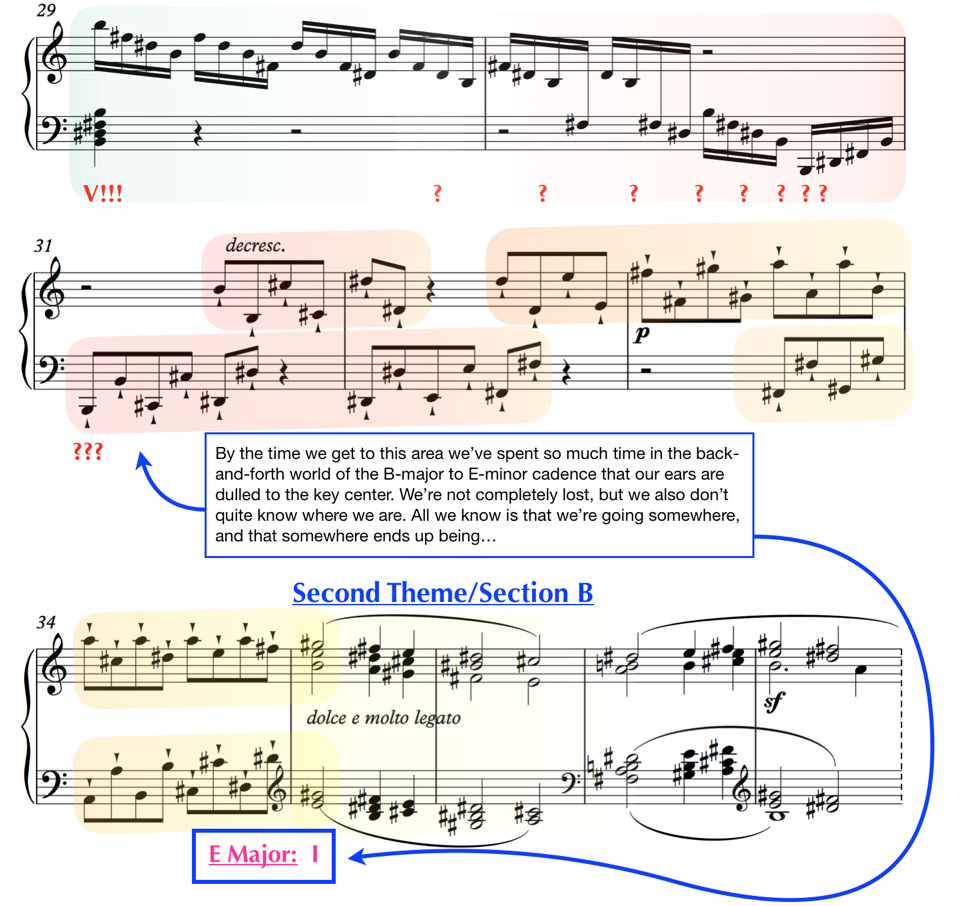

In case you’re not familiar, sonata form is a kind of musical form structure that features three sections: an exposition, a development, and a recapitulation (which is typically just the exposition again with some extra stuff and things and without a modulation).

Here is a basic diagram of sonata form. Take special note of the Roman numerals at the bottom of the diagram—they are referring to key-centers based on the initial key (e.g., if our piece is in A-Major then I will be the key of A-Major, V will be the key of E-Major, vi will be the key of F#-Major, etc.):

Due to its natural balance and the effectiveness with which it can provide a structured but fertile framework for musical creativity, sonata form was arguably the most popular form for composers to use when composing the first movements of symphonies and sonatas during the Classical Era.

For our purposes we will be focussing on the exposition. For a more thorough introduction to sonata form, see our video on the subject here.

The exposition portion of sonata form typically features two themes, an opening theme and a secondary theme that shows up about halfway through. While there are more components to the exposition as a whole, perhaps the most important feature is the modulation between the starting key and the key used for the second theme.

Take another look at the diagram of the exposition, and take special note of the indicated key-centers:

If we’re in a major key, we’ll be modulating to the key of the Dominant (V), and if we’re in a minor key, we’ll be modulating to the key of either the V or the III chord (known as the mediant in music theory speak).

And now for the important bit…

These specific modulations were essential for anything composed using sonata form in this period.

Wow. Ok, let’s think about this for a minute…so you had to go to the V if you were in major key and the V or III if you were in minor key?

Yes.

You couldn’t, say, modulate to the ii or the iv or the IV?

Not if you wanted people to take your music seriously.

And how many sonatas were written during this time?

Lots…

Recall that in the introduction of this section we mentioned an “underrated” convention that carried a tremendous amount of weight for those writing music during this era? This is it—this necessity within sonata form to modulate to these specific key centers at these specific spots in the form.

Why is it underrated? These days, the idea of having something so restrictive as a particular modulation attached to a particular form that holds such a position of prevalence within our musical diet seems pretty ridiculous. Make no mistake, lots of music still follows similar formats in ways that we don’t even notice in simple listening, but that has much more to do with the effectiveness of those musical routes than with any social need to use them.

Back in the day (the powdered wig, knee-high male stockings, and waistcoats day), however, modulating to anything else in the context of a sonata form would have most likely sounded wrong. It would have sound strange and off, and like the composer did not know how music, in general, worked.

Yes. Really.

And such a feeling was not specifically reserved for sonata form; most major modulations from this period trended towards the dominant or relative keys. Anything else was risky, and even uneducated listeners would have interpreted unconventional modulations as exceptionally weird.

In the modern day, we can basically modulate wherever we want, whenever we want, without nearly so dramatic a risk of it sounding ridiculous. It might sound strange if not done in a way that fits the musical context, but there no longer exist the kind of social barriers that made certain modulations during the Classical Era an institutional requirement.

So how did we get from a time of major restriction to virtually unlimited freedom?

Well, it kind of took a superhero…

First though, we need just a bit of background concerning why things were the way they were back in the oh-so-powdery days.

Modulation and the Tethers of History

There were a number of factors that conspired to evolve this necessary modulatory structure during and around the Classical Era. A detailed summary of these factors is beyond the scope of this article, however it’s worth mentioning a few points.

First, music of Europe during this period was still very much influenced by the tuning habits of history, which presented certain logistical options for composers. The tuning system most commonly used in modern times, known as Equal Temperament, had not yet become the standard by the late Renaissance and early Baroque eras. Whereas Equal Temperament forces the note spacing of the musical spectrum into evenly divided units, older tuning systems typically valued the increased “purity” of certain intervals at the cost of complete access to every key. Put simply, in pre-Equal Temperament tuning systems, certain keys sounded more out of tune than others (and certain intervals sounded especially out of tune), but the trade-off was that many of the most commonly used keys and intervals (particularly the thirds) more accurately reflected the harmonics we find in nature. This limited the availability of modulations to the “in-tune” keys. While the choice of Equal Temperament had generally stabilized by the middle and later years of Bach, many musical conventions still behaved as though some keys were bound to sound nastier than others, and in some cases they still did. That said, tuning was, in general, no longer nearly the issue it had been in the past, and it wouldn’t be long before that particular aspect of musical restrictiveness lost its power completely.

Second, the social norms of the period valued order, stately-ness, and elegant movement. Jarring or sudden changes were frowned upon, or they needed to come from a place of cheeky humor or extreme emotional duress (which was also generally looked down on).

Finally, modulation was not yet considered an area of great opportunity for composers looking to flex their creative muscles. Make no mistake, creativity was a valued musical asset, but it was only really considered valid if it adhered to certain restrictions of style and design. To the people of this time the ability to be creative within those boundaries demonstrated skill, and no one had yet come along who was willing or able to view the boundaries themselves in the light of creative potential.

Then, in the late 18th century, came along a scruffy-haired youth who was able to do just that, and who’s contributions to music would redefine what music was capable of for centuries to come.

Mighty Moves

The impression on music left by Ludwig van Beethoven (1770—1827) is apparent to even those with little knowledge as to what it was he actually contributed. After all, if you’re the guy with the most recognizable theme in the world (particularly if that theme is only four notes long) you must have done something decent…

The measure of Beethoven’s influence encompasses a vast area of musical development. He set new standards for everything from thematic development to formal scope and size to orchestration. He also, as you might imagine, made some major strides away from the restrictions of key modulation, and it is that innovation that we’re going to focus on here.

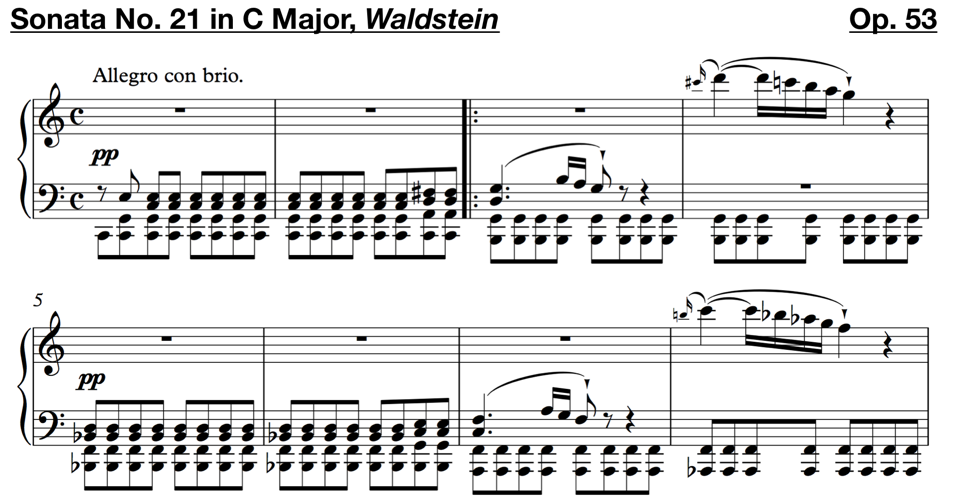

To accomplish this, we’re going to look at the exposition modulation in one of Beethoven’s most well-known and beloved works, the Piano Sonata No. 21 in C-Major, Op. 53. Dedicated to one of Beethoven’s patrons, it is also known as the Waldstein sonata.

Written in the earliest years of the 19th century, and completed in 1804, the Waldstein is a flagship piece of Beethoven’s Middle Period, which was characterized by an increasing technical depth and breadth of his works, an often soaring and grand expressivity (this period is also known as his “Heroic” period), and a subversion of traditional modulations and key-movements.

Here is a recording of eminent Beethoven interpreter Richard Goode playing the Waldstein. While we encourage you to listen to the entire work, due to the size of it we are only going to look as far as the modulation to the second theme.

Beautiful piece of music, isn’t it?

Now, that said, aren’t you offended by that second theme modulation?

If you answered “yes” then you’re probably reading the wrong article.

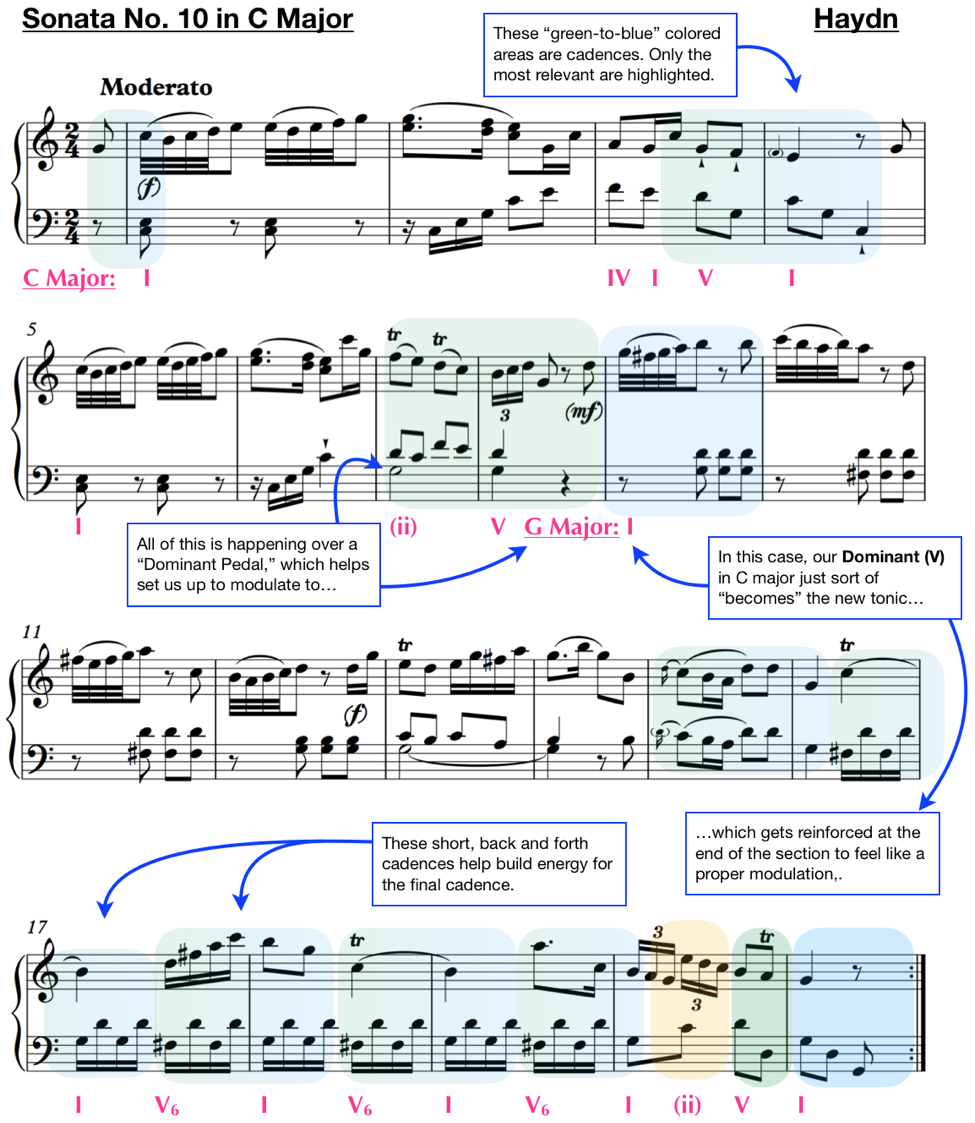

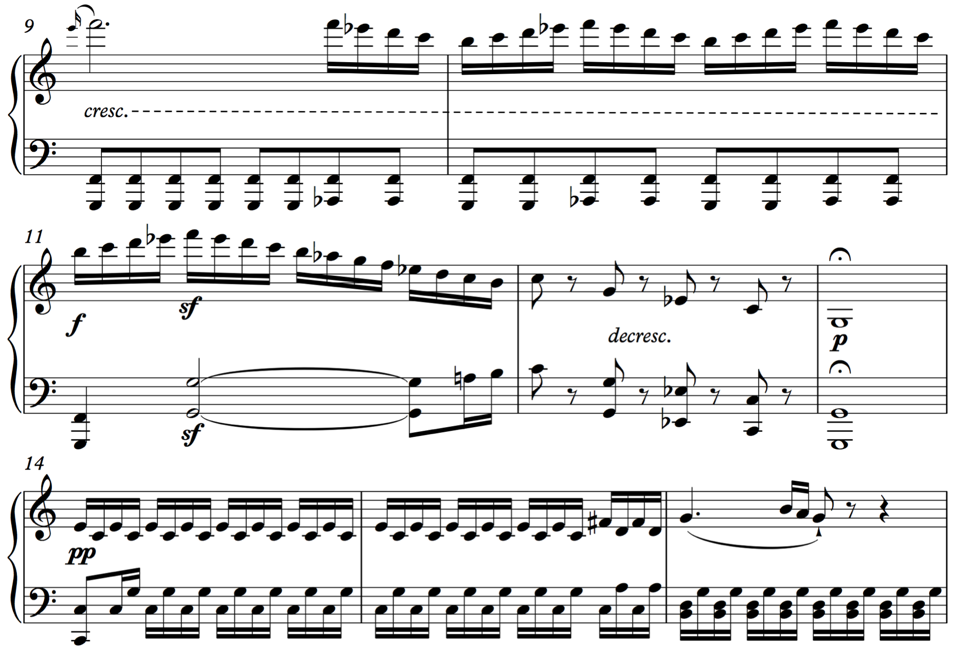

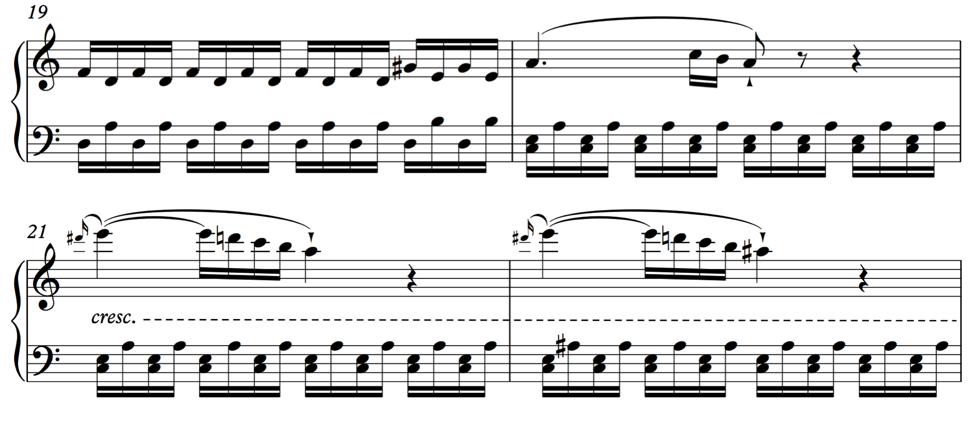

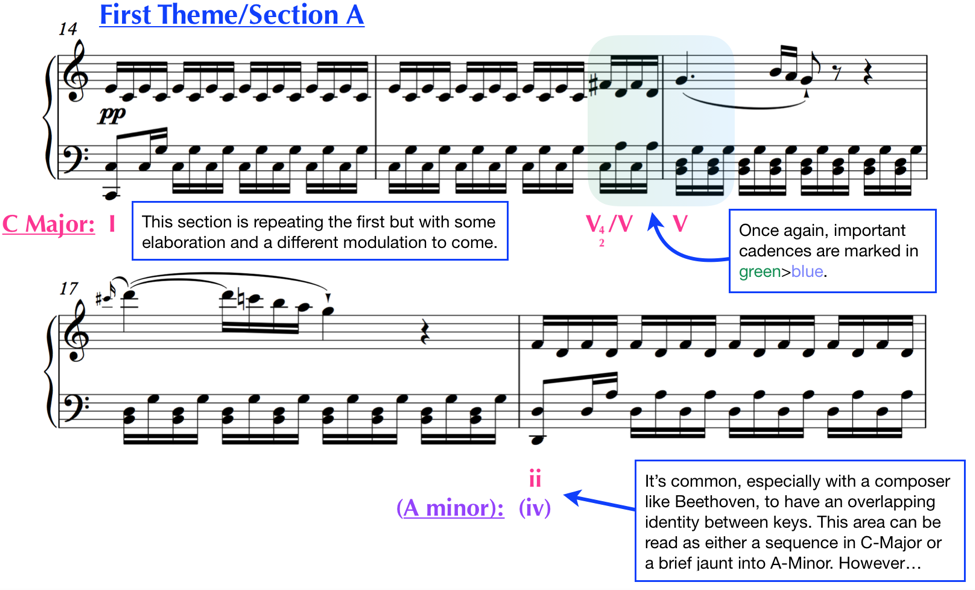

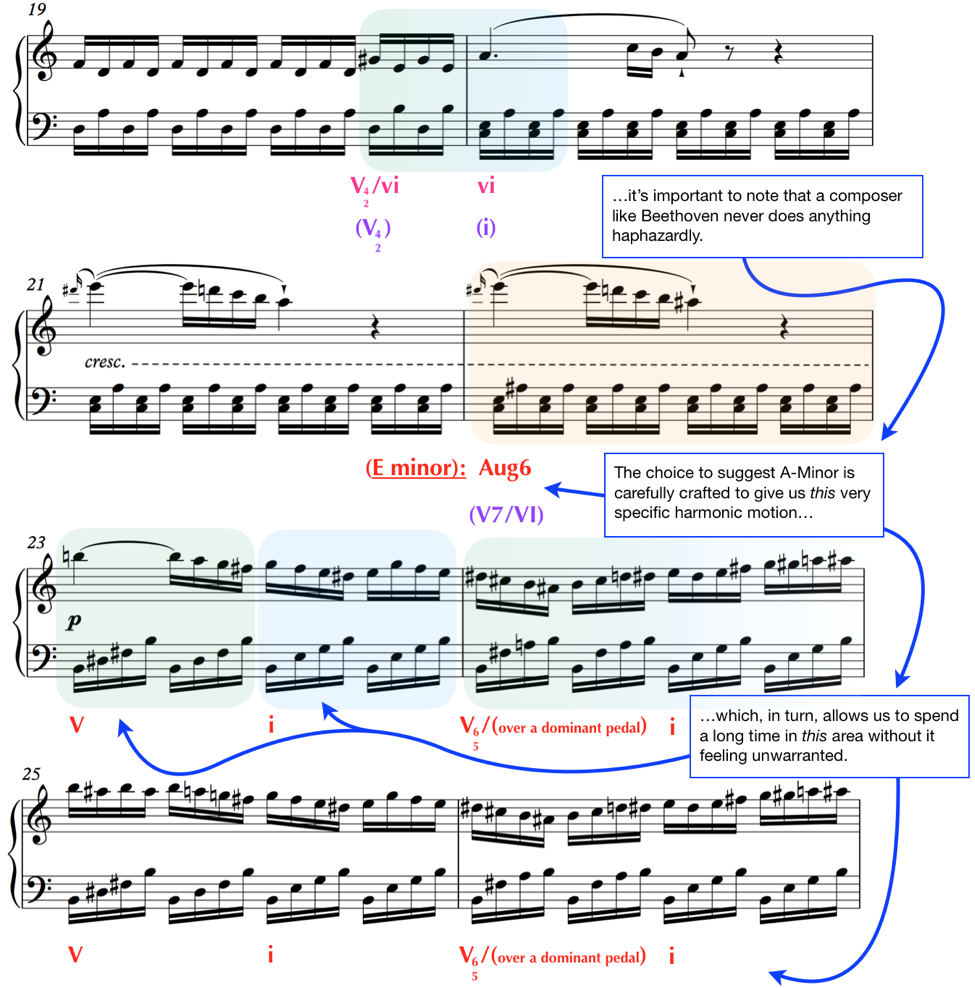

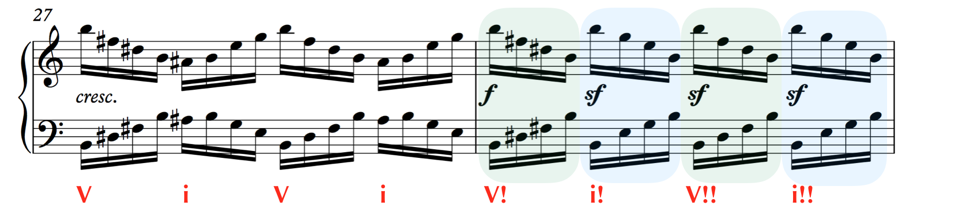

Let’s look at what that modulation actually is. To do this we’re going to present a slightly unconventional, annotated version of the score, starting with the return and elaboration of the opening theme on measure 13:

Our condensed diagram version of this modulation looks like this:

That’s right, we’ve modulated to E. E!!

What is the chord E-major in the key of C-Major? Well, pretty much nothing.

And yet, it’s also kind of everything. Part of what Beethoven proved with this is that, under the right circumstances, almost any kind of key relationship is possible, as long as you provide the right framework and context.

To illustrate, while Beethoven didn’t choose a key based on a common chord to modulate to, the note E is, at the very least, part of the C-major scale. In addition, the elaboration of the initial theme from measure 13 on allows Beethoven to put focus on the secondary dominant cadences such that when we land on the vi chord (A-minor), it doesn’t seem crazy at all to slide right up to the B-major secondary dominant of E-minor, and then to hang out there between that secondary dominant and its tonic of E-minor, like, forever. By the time we actually get to the rising broken octaves that are leading us to E-Major (that key we totally should not be modulating to…), it’s already too late and that final arrival to that key really doesn’t feel odd at all, does it?

Whew. And that, dear friends, is how Beethoven broke everything.

To our ears, the easiest way to hear just how different the modulation from C to E compared to a modulation from C to G is simply to play the tonic chords in succession: play a C-major chord to a G-major chord several times in a row, and then do the same with C to E. Quite the difference in sound when heard like that isn’t it?

This kind of modulation set the precedent for an unfathomable expanse of musical evolution. Almost every film score you’ve ever heard has employed some sort of derivative of this change, and much of the “limitless” of today’s sonic environment exists as it is because Beethoven thought it would be super sweet to do something other than the status quo, and to do it in such a fashion that nobody could deny its value.

So the next time you’re watching Star Wars or listening to, well, just about anything composed after 1827, tip your hat to Beethoven for making it possible.

Jazz Cats Need Twelve Lives: A Different World of Keys

Throughout this series we have focused almost entirely on keys as they pertain to classical music. More specifically, we’ve focused on them as they are represented in music written out in full notation. However, one of the most significant roles a knowledge of keys can play in music is as a structural vehicle for improvisation, and, in that light, the most common kind of music for people to think of when they think of music improvisation (or improv), is jazz.

Before we get to jazz however, let’s clarify something: improvisation did not start with jazz. Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, Liszt, and many other performers and composers we typically associate with written classical music, were all fantastic improvisors, and none of them ever heard a jazz lick in their lives. Before falling out of vogue in the middle and end of the 19th century, classical improvisation could be found in the form of Fantasy-style interludes, accompaniment figures, or entire cadenzas in larger works such as concertos. Improvisation has also long been a feature in folk musics, as well as in the rock/pop music that evolved out of jazz’s sibling on the streets, the blues.

All that said, the concentration jazz places on improvisation has evolved the practice into a highly dynamic mode of musical expression within the genre, and, as a result, the study and practice of jazz is now considered equivalent to classical music as an engaging and academically worthy musical pursuit.

While we’re not going to delve into the history or practice of jazz, we are going to show how thinking in keys is essential for getting started in the world of jazz improvisation, and how a similar knowledge can be applied to almost any style of key-based improvisation.

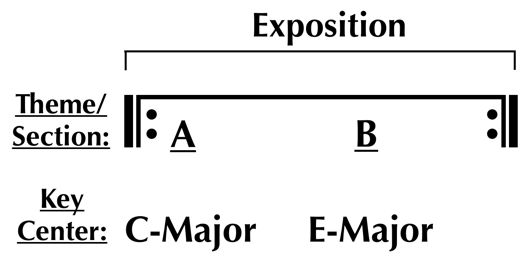

To do this we’re going to take a detailed look at one of jazz’s most respected and well known standards, the Johnny Mercer tune Autumn Leaves.

Boo-boo-bee-doop!

Jazz tunes do not have definitive versions quite the way classical pieces do. There are no renditions that are “the right” rendition. Most jazz standards have been featured in excellent demonstration on hundreds, if not thousands of recordings, so really it’s about choosing the recording that best suits what you’re looking for from the piece in question.

For our purposes, we’re going to use one of the most classic renditions of the tune, featured on Cannonball Adderley’s seminal 1958 release, Somethin’ Else. This version features an all-star cast of Adderley on saxophone, Miles Davis on trumpet, Hank Jones on piano, Sam Jones on bass, and Art Blakey on drums.

This version does have a lengthy introduction, so do listen for when the song actually starts :50 or so seconds in. If you’re unfamiliar with jazz, you will hear the actual tune played once, and then the players will commence improvising over the chord changes of the tune until the end of the song, when the tune will return and the song will end. You are encouraged to listen to the entire recording, but we will only be focusing on the basic melody and chords for our example.

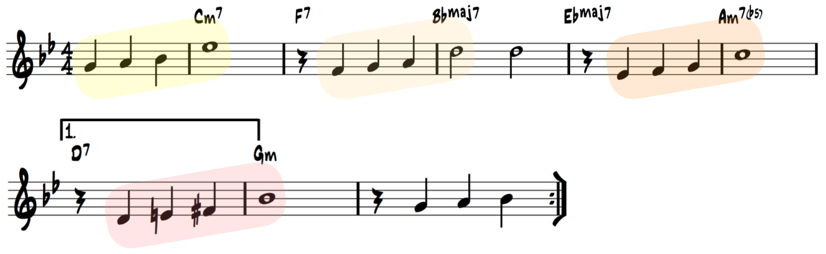

You can find the recording here. Follow along with the chart:

If you’ve never seen a jazz chart before, the first thing you’ll probably notice is how sparse it looks, especially when compared to the amount of music that is featured in that recording. You might have also noticed that Miles Davis does not play the tune exactly as its written.

One of the most prominent features in jazz that differentiates it from classical is its hybridized tradition of written and non-written musical communication. Jazz musicians are expected to contribute their own musical knowledge to the common framework of the jazz chart to create a complete vision of the music. Remember how we started this whole series with articles about chords and scales? Well, in jazz the depth of the player’s knowledge of chords, and the scales that can be used to improvise over them, is an essential feature of initial study. Most jazz music charts only give the minimum of information necessary for the players to work with, so the players must fill in the rest themselves.

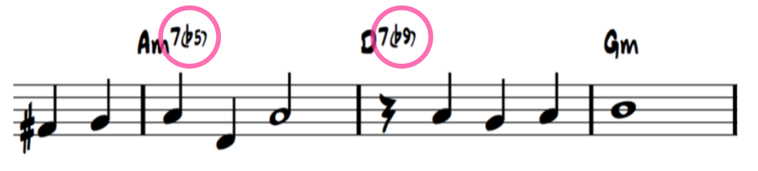

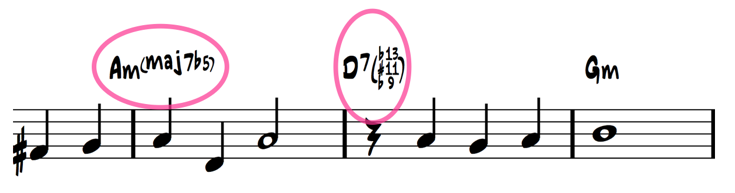

You might also notice that our chords have some interesting attachments:

Do you remember our talk of extensions in our early article in this series on chords (What are Keys? Learning Chords)? Jazz makes copious use of extension notes to inject its harmonies with lots of subtle color and flavor. Jazz also has different tolerances concerning the movement of notes and chords, and is much more willing to harbor unresolved dissonances.

It’s important to point out here that jazz musicians will often freely add or alter the extensions of basic triads or 7th chords to achieve the variation of sound they’re looking for.

Finally, you might have noticed the discrepancy between the key signature and the starting chord.

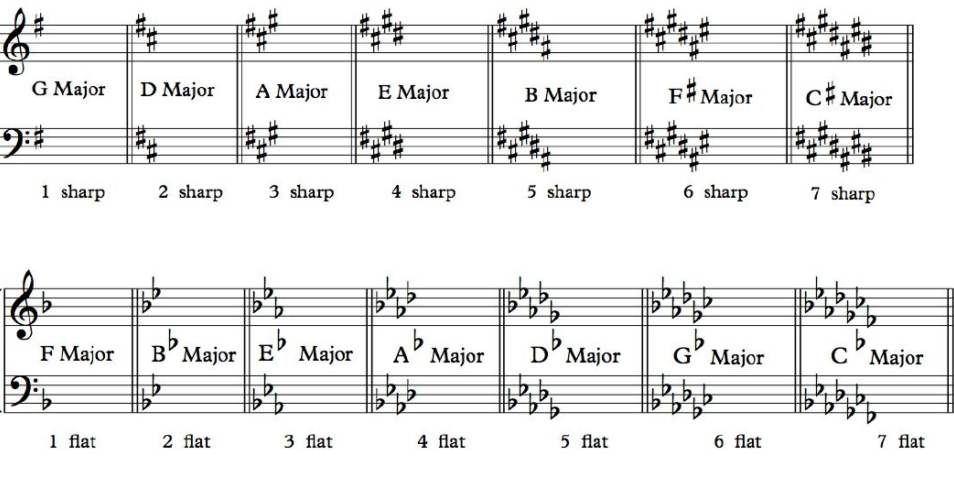

Using our knowledge of key signatures (or going to the Circle of 5ths for some help…) we know that this key signature indicates either Bb-Major, or its relative minor key, G-Minor.

Recall that in the classical music we’ve been looking at one of the main hints we have as to which key we’re actually using is which of the two tonic chords starts off the piece and ends the piece.

When is the first time we see either a Bb-Major or G-Minor chord in this piece?

Ah, there we are, bar 3 (“bar” is a jazzier way of saying “measure").

But something doesn’t feel quite right about that, does it? Does this feel like a piece in a major key? And what is the music itself doing? Those ascending phrases just keep going, sinking lower and lower like, well, falling leaves…

Ok, well how about that G-minor chord in bars 7 and 8? Do we think that’s the real tonic of this key signature?

Possibly, but in listening to this piece, does that sound like a really solid cadential arrival?

In fact, we really don’t get that arrival until after the second ending, with the G-minor chord on bar 10 (if we’re counting full bars from the top). This finally feels like the kind of arrival we’re used to:

Now, it’s important to mention here that pieces of music that start on chords that are not the tonics of their key signatures are common enough in both the classical and jazz worlds. For classical music in particular, a major preoccupation of composers from Beethoven’s time on was the increasing delay and obfuscation of the cadential arrival.

The major difference here is that in classical music the notes are written, so the player need not be too concerned with lacking a knowledge of the key as long as they can follow the notes, whereas in jazz the minimal notation means the player needs to be able to quickly locate their source of musical material in order to properly play the piece.

Enter keys.

ii.V. I

Jazz musicians identify their musical material by intimately familiarizing themselves with the chord progressions that commonly serve as the framework for tunes. They drill these progressions over and over, in all keys, working towards automating the movements between the chords and affixing the chords and scales to larger musical structures (like keys).

By focusing their practice on the component parts of music as much as on the music itself, jazz musicians are able to treat keys like a little box of tools they can use when improvising or accompanying with charts. Despite the absence of functionality identifying features such as the Roman numerals we’ve been using to analyze our classical works, jazz musicians are trained to assign function to chords and chord progressions on the fly, and to establish the scales and keys they require to make the music happen. Jazz musicians still use some of these tools of analysis in study (such as Roman numerals), but when showtime comes, all they have is their charts and whatever depth of experience and practice they’ve managed to compile.

So how then do keys work for a jazz musician?

The first and most basic chord progression any jazz musician learns is actually a cadential progression built using the ii chord, the Dominant (V) chord, and the Tonic (I) chord.

This is colloquially called a ii-V-I when referencing any instance of this progression found in the music.

Knowing the sound and feel of a ii-V-I (or i, if in minor), affords jazz musicians an instant reference point to a key, which gives them both the scale and the functionality of the chords they will be using.

For example, if we see a ii-V-I ending with a G-major chord I, we’ll know that we’re very possibly in the key of G-Major, which tells us that we’re using the G-major scale, and also how other chords in the vicinity might behave as subjugates of the key of G-Major.

Very handy, yes?

The issue is that, unlike much of the classical music we’re used to hearing, jazz has no problems either instantly changing key (without classical music’s built-in modulatory smoothing, that is), or leading us down a long and winding path before we actually get to our key-identifying ii-V-I.

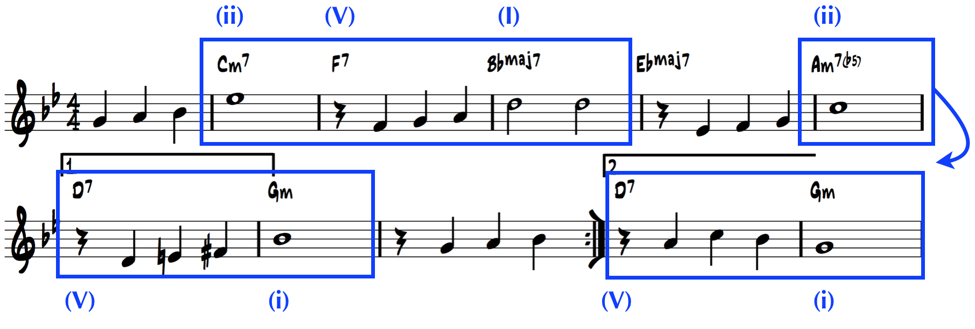

Let’s take another look at the opening phrases of Autumn Leaves to get a better sense of this:

Looking closely, we can see two ii-V-I structures, one seemingly in major, the other in minor (consider the first and second endings the same ii-V-i):

As we’ve already decided, it is the second ii-V-i (landing on the G-minor chord) that is giving us the true confirmation of the key.

Does that mean then that we’re playing in two different keys already at the beginning of this piece?

Not at all.

Once a ii-V-I has been identified, one of the more effective tricks we can use to determine how far its influence goes is to work backwards.

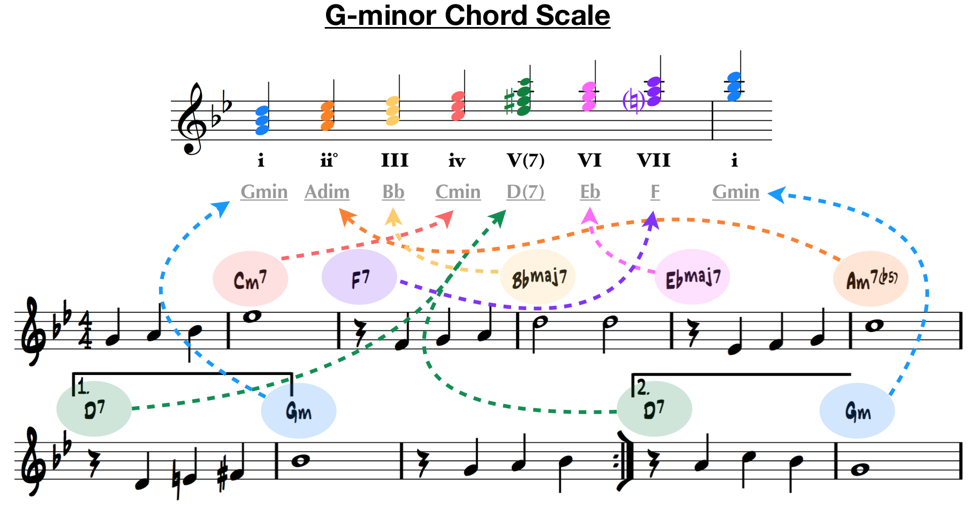

If we call that G-minor chord our Tonic (i) in the key of G-Minor, let’s see how many of the chords that precede it fit into the G-minor chord scale:

As we can see by comparing Roman numerals, all of the triads of the chords from the piece correspond with the triads from our chord scale. Notice that we did alter the D chord to make it the Dominant (V) of the scale, but otherwise everything fits nicely. Indeed, even the added 7ths from each of the chords in the piece (which we’ve omitted to present a more visually simple chord scale) would still fall into the G-natural minor scale. We can also see that we have every single chord from our chord scale represented in the piece.

Looking at it this way, it should be very clear that the key we should be thinking in is G-Minor, and the scale we should be using to improvise with is the G-natural minor scale.

Jazz musicians are trained to take all of this in at a glance, and to boil it down to one simple guideline: key of G-minor.

Autumn Leaves, while a classic, is generally considered an easy jazz tune due to its lack of any real modulation. There are a couple of sequences and re-harmonizations built into the tune, but otherwise it stays in the same ket throughout. In many other jazz works, ii-V-I’s will happen in quick succession, and each will actually take place in a different key, requiring the player to deftly adjust the scale they are using to improvise with. And if that weren’t enough, the extensions that players use with their chords also necessitate changes to the scale, resulting in some interesting mutations of the major and minor scales.

This idea of using cadential progressions (or even just commonly used progressions) to identify the key for the sake of improvisation is hardly exclusive to jazz. The same principles can be applied to any sort of improvisatory music that utilizes keys. Jazz presents for us a very high quality example of what improvisation can be, but it is far from the only example. Everything from alternate forms of improvisation to classical composition to simple songwriting can benefit from learning keys the jazz way.

Beautiful Noises: A World Without Keys

Have you ever seen a movie trailer for an action or superhero film? If you haven’t, see if you can dig one up on YouTube, especially if it’s for a movie that’s come out in the past 10-15 years. What sort of music do you hear in these trailers? It all kind of a blend of big, chopped up orchestra parts and maybe some digital effects, right? Now, have you ever thought of the trailer itself as a production (as opposed to simply a preview of a production)? What happens to how we consider the music if we think of it like that?

Try this: Turn off or look away from the screen and try to experience these trailers just as a listener. Try to hear the entire aural presentation not as a stitched-together musical mutant attached to visual cues, but as a studio edited production unto itself, just like you might any piece of pop or electronic music.

How does a movie trailer work as an actual piece of music?

Strange cuts and sudden shifts. Harsh brass immediately juxtaposed with airy strings, cast against erupting walls of orchestral rage. Whirs and brrrs and buzzes and ssssssssnips. Maybe some metal guitar? And oh so many big, buzzing pulses that sound like the malevolent roars of some monumental robot invader (always my favorite, no matter how many times I hear them…)

And that’s simply from what we might most easily be able to call the music part of the trailer, not including the movie’s own explosive effects and effectively explosive one-liners.

Is this music? Can we really stand this next Beethoven’s sonatas or Miles Davis’ melodious improvs or Michael Jackson’s “Thriller” and call it music?

Whatever your thoughts may be on the subject, when heard and seen together in trailer form, we don’t give it a second thought. It is part of our modern audio world, music, effects, and all.

The reason for this acceptance boils down to context—when accompanying the images on the screen, this amalgam of musical brutality seems entirely appropriate. Films themselves often have this trait as well: Have you ever listened to a horror film soundtrack without the horror film to accompany it? It can be an awfully strange experience…

And yet, musical experiences that seem more like sounds than music to us as modern day movie watchers and music listeners have precedents in the world of classical and jazz music. Try listening to a Xenakis orchestral work, or Penderecki’s Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima. Try listening to John Cage’s Variations II, which features renowned pianist David Tudor manipulating the piano with electronics and unconventional techniques. Try listening to freewheeling, occasionally spastic free improv of Cecil Taylor.

These composers and performing artists, with their occasionally crazy sounds and unconventional musical landscapes, are also an essential part of our musical history.

And the most important part in all of this for us?:

In all of this music, there’s not a key to be found.

This is the world of post-tonal music, which is a really music theory-nutty way of saying “music that doesn’t use keys.” The word “tonal” here is derived from Western Tonal Theory, which is the official version of the theory of keys that we’ve been covering in this article. There is more substance and detail to be found in Western Tonal Theory (or simply, tonal theory) than we’ve presented throughout this series, however a pursuit of that study is a much more serious endeavor, and more than we need for the purpose of understanding keys to the degree at which we generally need to for everyday use.

What we’re really after here is the concept of a musical world that doesn’t rely on keys as the driving force behind its creation. This can be truly key-less music (such as the post-tonal music of Schoenberg or Pierre Boulez), or simply music that is constructed primarily without the idea of keys at its center. For example, a lot of electronic music employs harmonies that we might think of as being part of a key, but is definitely not constructed by a producer thinking to themselves, “ok, key of A-Major…”

Why are we seeking to explore the world of music without keys in an article series about keys? Because so much of the music of today is influenced by the music that evolved after the language of keys had been exhaustively explored.

That movie trailer you watched earlier? The movie score for the movie itself? That dance song you heard over the radio? That one weird sound effect you heard in that ad you had to sit through on YouTube before you could watch the trailer you watched earlier? All of this would not be possible if at some point, people had not decided that music could exist beyond keys, that it could include and illuminate soundscapes that conforming to the relatively strict rules of key-based composition would not allow.

For our final section in this article series we will take a brief look at some musical developments in the piano world that lead to some of the first post-tonal music.

Mysterious Tweets and Odd Angles

As usual, it all really starts with Beethoven, Breaker-of-Worlds…

By the end of his life, Beethoven’s compositions were massive, dense, and to many of his contemporaries, somewhat incomprehensible. The Grosße Fuge (Great Fugue), an enormous double fugue for string quartet, left many critics of the time scratching their wigs, while the technical demands of late piano sonatas such as Op. 109, with its third movement marathon of trills, or the hammering chords of Op. 106, the Hammerklavier sonata, sent many pianists running for the verdant Austrian hills. The 9th Symphony, while a great success at its premier, is a vast, verging on programmatic work in which Beethoven seems to tear at the constraints of Classical sensibilities as he seeks the ultimate truth in musical significance.

This is the stage set for the developing Romantic Era (c.1790—1910), in which musicians would explore the expressive potential of music to varying degrees of emotional extreme and impropriety. Naturally, such explorations warranted certain evolutions of music composition and execution, which is where we will start our own explorations.

While Chopin very clearly set the standard for what the Romantic musical language of the piano should sound like, other composers of the time were probing its boundaries, looking for entrances to different and distant musical realms.

One of the most notable of these composers from the early-middle part of the 19th century was Robert Schumann (1810—1856), who combined an adventurous sense of harmony and phrase with some ultimately tragic mental health issues to develop some of the more fascinating and fantastical works of the time.

One such selection, from one of Schumann’s late and great piano series, Waldzsenen (Forest Scenes), exhibits a fairly unusual soundscape that’s more sonic environment than sensuous song.

As you listen, imagine you’re walking through a mysterious forest and follow along with the score to Vogel als Prophet (Bird as Prophet):

Quite different than what we’ve been hearing so far in this series, yes?

There are a couples of things to notice here.

Perhaps the most obvious point of interest are the odd, rapid figures we can only assume are serving as the voice of the titular “bird-prophet." To say that these constitute an unusual presentation of melodic material is something of an understatement, and one can very easily imagine these going horribly awry in the hands of a less skilled composer. Instead, Schumann constructs them into a unique phrase structure for the purposes of navigating an equally unique harmonic narrative.

Which brings us to the key-scheme.

What key is this in, anyway? By the key signature itself we would think that this is either G-Minor or Bb-Major. After a disconcertingly unconventional statement of G-Minor in the first couple of bars, we somehow land in the world of Bb-Major at the end of the first phrase in measure 4. And then we begin the next phrase immediately in D-Minor, who’s only real relation to what has come before is that it’s the minor v of G-minor. And where does that go?

F-Major. Obviously.

Hopefully it’s clear that we’re being sarcastic here to emphasize how unusual all of this is in comparison to the well established rules and regulations we’ve been familiarizing ourselves with thus far.

This kind of subversion of the elements of music, from the rhythmic and melodic material to the key-scheme to the accompanying dynamics, is one of the major ways in which composers began to tear at some of the traditional constraints of keys. For many, the most crucial restriction to overcome was their own sense of concept. Despite the weight of his personal quirks, there is no doubt that Schumann was possessed by the need to express a powerful and demanding concept, and he forged his music to meet those demands.

It’s important to note here that, while unusual and evocative, the musical elements in this piece still generally adhere to certain traditional standards.

We still have 4-measure phrases and we still have cadential arrivals. We still have at least some sort of relation between keys. Most importantly, we are still using the basic, core components that we first introduced in this series (chords and scales) as our building materials.

Once we start messing with those, we’ll really be on our way to a different musical world…

Give a listen to Franz Liszt’s seminal little piece for the piano, Nuages gris (Grey Clouds):

Once again, a very unique soundscape developed using some unusual manipulations.

The compositions of Franz Liszt (1811-1886) are much better known for their astonishing technical pyrotechnics and piano competition viability than for the deliberate iconoclasm seen here. With so much of his music wrapped up in technical obsessions, it can be easy to overlook some of Liszt’s more subtle, but no less important, contributions to how we think about harmony and keys.

While we can point out some traits that are similar between Nuages gris and Schumann’s Vogel als Prophet, such as the uniquely presented phrase structure and tonal ambiguity, what we’re really after here are the treatment of the chords we see after the opening phrases.

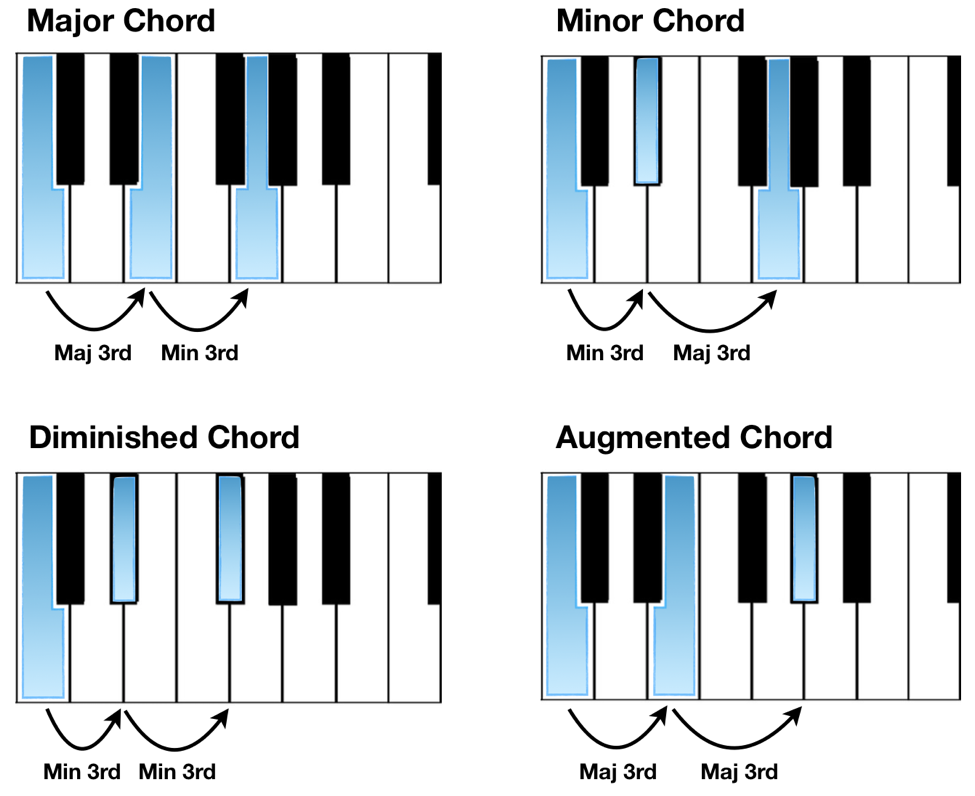

Recall that we have three kinds of triads: major, minor, diminished, and augmented. Remember too that all of these chords are created by stacking different kinds of thirds:

Lastly, recall that the basic identity of most of the chords that we see and use are based on either the major or minor triads at their base. Here it’s worth mentioning that this is a predominant feature of identifying stable chords, or, chords that feel like they can stand alone without the need to resolve to another, more stable harmony.

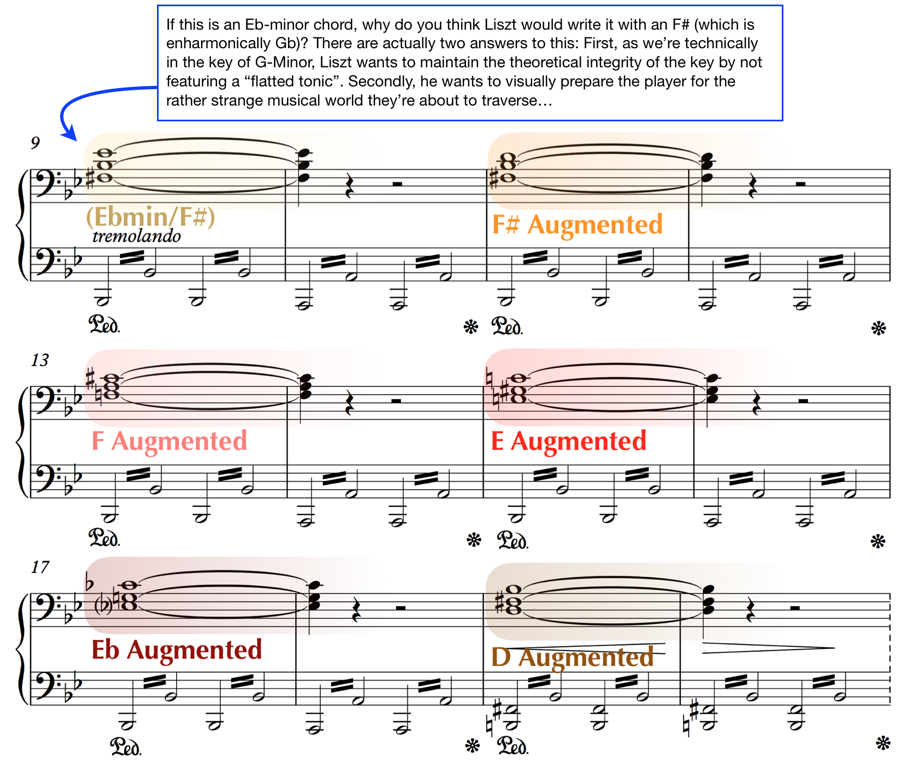

Let’s look at the chords in Nuages gris that start on measure 9, and identify their type as we go along:

What a nice, beautiful, long line of…augmented chords?

Nuages gris is perhaps the first piece to present augmented triads as an independent and essential harmonic structure, instead of one that needs to resolve to a more stable major or minor sonority.

The importance of this for us regarding keys is that the augmented harmony does not fall into either the major or natural minor chord scales, which means that, as a harmony, it lies outside our normal harmonic considerations, and needs special placement and resolution to “properly” be a part of a key.

In Nuages gris, Liszt is showing us a new musical context in which a sound that previously had been thought of as reliant on other musical elements to function properly can be a legitimately functioning element on its own.

This is the recasting of the core components of music that really starts to dethrone keys as the unassailable basis for music composition. From here, it was only a matter of time before someone came along who decided that we could really just do away with keys all together…

Shapes in the Water

Meet Claude Debussy (1862—1918): He’s charming and witty, hard-working, and connected, introspective but cosmopolitan in only the most sought after of ways any self-respecting man of France in the late 19th century should be. He might be a little off-kilter and a touch self-centered, but he’s a devoted counterpart, and an ambitious self-promoter.

He’s also kind of an ok composer…

Actually, in all seriousness, few composers carried quite the weight of influence on the classical world of the 21st century like Debussy. While popularly known as the composer of whimsical and beautiful works such as Clair de lune, Debussy’s real musical weight is carried in works that haven’t quite managed that level of public appeal in modern times. In terms of the influence of his sound, however, his musical developments are widely considered to have marked the crossover point in Western art music between the Romantic and Modern eras.

To be sure, the lines of influence are somewhat more detailed than that. Other composers of this period whose ideas proved indelibly influential to the modern musical world to come include the tempestuous and astonishing autodidact Richard Wagner (1813–1883), the refined and ceaselessly adroit Maurice Ravel (1875–1937), and the often underrated minimalist Erik Satie (1866—1925).

However, regarding the composer who took the first real steps towards conceptualizing and executing the manner of ideas and works that the Modern Era would become known for, Debussy is almost certainly the top choice.

While there are a number of factors in his music that help it achieve such standing, perhaps the most important (as you might imagine given the nature of this article series) is how it ultimately eschews the world of tonality, the world of keys, for more evocative modes of musical expression.

What does such “eschewing” sound like, you may wonder?

Let’s take a listen to the first movement of Debussy seminal piano sweet Images, Reflets dans l’eau (Reflections in the Water). Follow along with the score on here.

Listening to this, it is likely that some of your first thoughts do not include this one:

“Wow, listen to how that music doesn’t use keys!”

Indeed, the guise of beauty here is very effective, and it would have to be; the world was not simply going to accept the abandonment of keys for some chaotic hodgepodge of notes. We still have some of the trappings of keys here, but they are, in the very best sense of the word, vestigial.

Our key signature of Db-Major is emplaced more as a convenience to indicate that we will be generally hanging out with the Db-major scale, however, beyond that, very few of the traditional characteristics of keys find a home in this music. We do sustain a tonic-esque groundwork (look at how the Db lingers in the bass through the opening phrases), however any sense of the classic sound of the cadence or of chord progression has dissipated like…well, like ripples across water. Instead we have different factors that function to give the music cohesion from mimicry of chord structures to suggestive phrasing to the careful placement of fortifying bass notes.

A true study of this music is an exploration for another article, but we wanted to form at least some kind of connection between the seemingly unlimited sonic world of today and the fairly tangible development of musical sound that has served as its precursor. It might still be a bit challenging to put on some headphones and imagine the clashing bedlam of movie trailer music coming into one ear and the graceful swells and subtle colorations of Reflets dans l’eau coming into the other, however, think of it like this: if we were to ask Beethoven and Debussy to write music for an action movie trailer, Beethoven would probably write explosive music, whereas Debussy would write musical explosions, and lots and lots of beautiful noises…

Conclusion: What to do Now?

Before talking about some of the practical ways our new-found understanding of keys can help us develop our musical skills moving forward, let’s take a brief look back at the path we walked to get us here:

- In the What are Keys?: Learning Scales article, we looked at the construction and naming of scales, and talked about how we think of scale degrees as the groundwork for the melodies and harmonies we use in our key-based music.

- In our third article, What are Keys?: Learning Chords, we performed a similar operation with chords, and introduced chordal figuration and chord progressions as common features of music that uses keys.

- Then, in our article, Discovering Keys: Part I, we transformed our reinforced knowledge of scale/chord basics into the core components of keys, illustrating how we can use scales and chords as our key infrastructure, and demonstrating some of their essential functions as representatives of a key.

- We followed up by emphasizing the importance of the cadence as an identifying feature of keys in our article, Discovering Keys: Part II, and then embarked on an exploration of how musical elements not featured in our key (i.e., non-scale tones) could be used to help reinforce and enrich our key’s identity.

- Next, we spent some time on the darker side in our article, Discovering Keys: Minor Keys, in which we detailed some of the unique specificities of the minor scale, and talked about the differences in thinking between music in minor keys and music in major keys.

- Finally, in this article, we took an exploratory look at some of the notable uses and developments of keys in various musical settings, from the evolution of modulation in Beethoven, to the basics of thinking in keys like a jazz musician, to the movement away from keys that prefaced many of the musical innovations of the 20th century and today.

So how exactly can you take all of this and apply to your musical training?

There are numerous ways in which a knowledge of keys can practically benefit you in your studies. Here, in no particular order, are some thoughts, suggestions, and tips for how you can incorporate keys into your day-to-day musical life:

1. Practice your scales!

Yes, now you know that everyone’s favorite technical exercise is more than simply track-laps for the hands. Knowing your scales is one of the easiest ways to reinforce the groundwork of keys in your fingers such that it comes easily when you’ve identified the key and know which scale to use.

2. Identify the key for each piece you learn by combining the key signature with the sound of the cadences at the beginning or the end.

This is another excellent habit to get into, and one that will serve you well when you delve into deeper and more advanced pieces that either change keys often or outline their keys ambiguously.

3. Know your chords.

After identifying the key of a piece, you should be able to scan through the harmonies and more easily be able to identify (and subsequently play) chords and broken chord figures. This works the opposite way as well; being able to identify some of the chords present in an area of music can give you hints as to what key you might be working with depending on what they are and how they’re behaving.

4. Improvise using keys.

You need not be a student of jazz to benefit from the practice of improvisation, and one of the easiest ways to get into improvisation is by picking a key, picking a chord progression that sounds good (usually one with a cadence at the end), and improvising over those chords using the scale of that key. The accompanying chords can be played as simply and in whatever fashion you’d like. As you do more of this you’ll discover preferences for sounds and harmony motion, exercise the stability of your ambidextrous playing, and accumulate a sense of identity for the sounds you encounter in the music of other composers.

5. Learn common chord progressions.

As we’ve mentioned throughout this series, most music that is based in keys (and much that is not) employs commonly used chord progressions. Knowing these progressions, either by analyzing and understanding how they work in the literature or by figuring them out and putting them into improvisation exercises, is a guaranteed way to improve your ability to work with music that uses keys.

6. Practice “deconstructing” your pieces into their component parts.

This is all about making your understanding a reality when you’re learning a piece of music. Practice simplifying elements of the music using your knowledge of how they’re constructed such that you can more easily focus on a particular area. For example, you might simplify the Alberti Bass of a Mozart sonata into chords so that you can more easily focus on the melody without losing the harmonic background:

7. Listen for and try to identify the telling characteristics of keys when listening to music.

Can you hear the sound of a cadence? Can you feel the potential energy building in a dominant chord that is gearing up to resolve to a tonic? Can you tell when the music has changed keys? Can you hear when elements of the music are not obviously a part of the key (non-scale tones)? Remember, all of these things exist in the music already—all we need to do is pick them out and learn to know what we’re hearing.

8. Practice in All Keys!!!

This is one of the most important things you can do as a practicing musician, both for your knowledge and understanding of keys and for your musical prowess in general. It can be as complicated as transposing an entire piece or chord progression, or as simple as taking a short melody and playing it in all twelve keys. You can also experiment by taking something that was major and putting it into minor (or visa versa), or by substituting some of the harmonies in a chord progression with ones that are borrowed from another key. However you decide to do it, making this a part of your daily practice will improve your skills in leaps and bounds.

Closing

The musical world of today is brimming with almost any kind of music experience you can imagine. With a few keystrokes we can hear everything from traditional European classical to avant-garde jazz, to pulsing electronica, to raging death metal. Live music outings can see you at decadent raves, gentle coffee-house folk shows, art-house indie bonanzas, or eclectic chamber concerts in the park. The film music today regularly presents stylistic variations and combinations of technology and composition that would have seemed rather improbable fifty years ago, and the prevalence of user friendly virtual reality is pushing video game composers to rethink the behavior and function of music in space. There is so much music in the world, in fact, that many music academics wonder if there’s anything else we can really add: Is there a new musical frontier waiting to be explored (or perhaps one being explored currently that hasn’t caught on yet)?

The most intriguing answer may be this: Does it matter?

A very fine mathematics educator once pointed out that while most math people tend to be music people, many music people are not math people. The point here is that music is not math—it does not progress like a line, one theorem or proof compounding on the one before it in service to the goal of forward progress. Music evolves in great waves, each circling back in the recession of currents before gushing forward again with both old and new waters commingling almost indistinguishably within the great tidal shifts of history. We constantly come back to age old modes of musical expression and technique, even as we’re constantly looking for new ways to realize and experience music.

Keys are one of the ageless bastions of musical design. We seek them and hear them without even noticing that we’re doing so, and they still sustain a deep presence in the modern world, both as representatives of history, and agents of creation.

We hope that you have enjoyed our article series on keys, and that hope that you now have a better sense of how they can aid you in all of your musical endeavors!