We’ve already covered a lot of ground in this article series on keys, however there is one important area that we’ve largely avoided in our studies thus far: minor keys.

Please note: if you haven’t had a chance to check out our previous articles in this series, particularly our article on scales (What are Keys?: Learning Scales) and Parts I and II of our Discovering Keys articles, now would be a good time to check them out. Much of the information in this article will assume some familiarity with the material from those articles, so now is a good time for some review.

Another thing you should do about now is listen to some music in minor. This might seem a little obvious, but we’ve been spending a lot of time living in the world of major keys, and if you’re generally unfamiliar with classical pieces in minor keys, it can definitely be something of a sonic and mental shift to delve into them.

While there are many good options for your consumption, here are my two suggestions:

What is it about Minor Keys?

So why are we devoting an entire article to exploring minor keys? After all, they share many of the same traits as major keys, and the general principles we’ve established of applying scales and chords to understanding how each key works are also similar. Furthermore, we use the same methods of identifying their scales and chords (and chord scales) as we do for major keys, and we can glean the same hints regarding their identity in the music via the key signature.

And yet, composers, both modern and historical, treat music in minor keys very differently from music in major keys. This is important; we’re not explaining some unusual theoretical trait or obscure musical formula, we’re illuminating the practices we see in the music itself. As it so happens, for music in minor keys, this means we need to make some unique contributions to the knowledge we’ve already gathered.

Fantastic. So what is it about minor keys that actually makes them different?

Just like with major keys, it all starts with the scale.

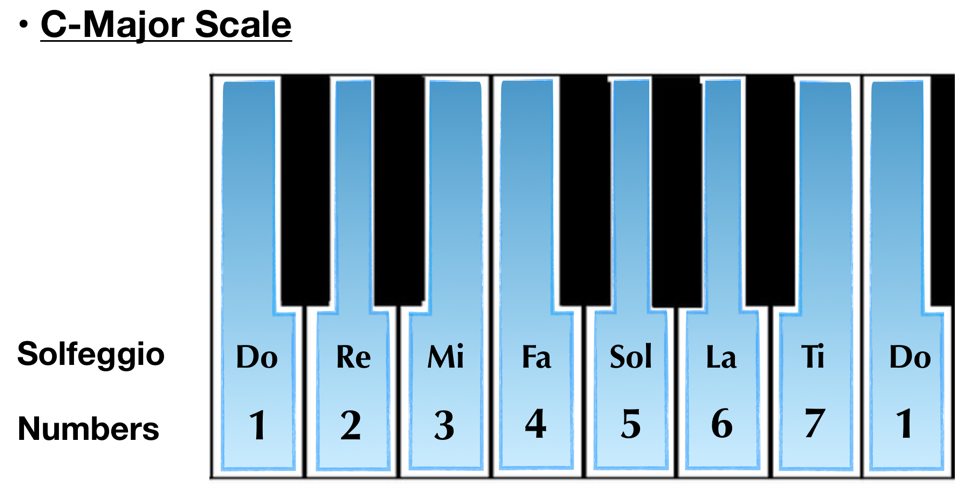

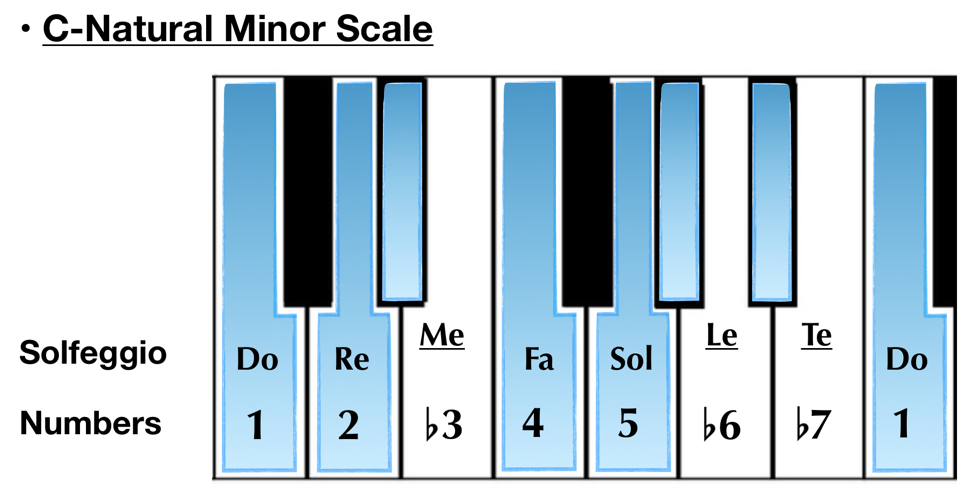

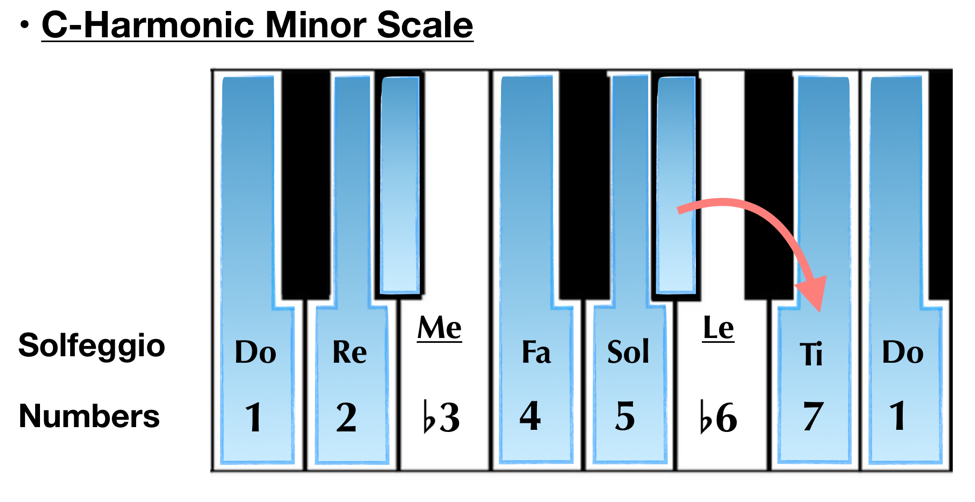

Below we have examples of the C-major and C-minor scales as we see them on the keyboard, with both our methods of naming the scale degrees included:

Take special note of the scale degrees that are different between the two of them. In addition, notice that while the numerical note names need only a prefacing accidental added to them to indicate the altered note from the major scale, the solfeggio-based note names require entirely different syllables.

Now let’s look at a different version of the C-minor scale:

Wait, what? A different version of the minor scale?

Yep.

Well, how many versions of the major scale are there?

Only one.

And how many versions of the minor scale?

Eh, at least three?

Three? At least!?

Yes, something like that…

So, obviously we’ve encountered our first major difference between scales used in major keys and those used in minor keys: there are about three different kinds of minor scales.

Why do we say “about three”? Let’s look at the “third” version of the minor scale that we haven’t seen yet to get some explanation.

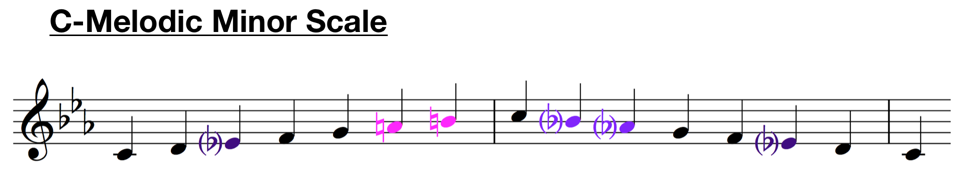

To view this scale properly we’ll need to look at it in notation:

As a quick reminder, the parentheses around the accidentals are a common way of indicating that they are already in the key signature. They are known as “courtesy” accidentals, and will be present at times throughout this article for visual clarity.

As we can see, the “melodic” version of the minor scale is different going up than it is going down. If you’re wondering to yourself why we wouldn’t simply have a version of the minor scale with the 6th and 7th degrees raised to their usual, natural placements and call that the “melodic minor” version, well…that’s where the “about three” comes from. We certainly could do that, however, based on what we see in the music, it ends up making much more theoretical sense to render the “melodic” version of the minor scale as a dynamic scale that is different going up than it is going down.

Don’t worry, we’re going to unpack all of this in the next few sections.

Gathering the Theory Bits

To reiterate, all of what we’ve just seen we derive from what we see in the music. The musical practices from which we pull these scales go all the way back past the time of Bach, and have very much to do with how composers discovered they could (and needed to) manipulate the minor scale to adhere to the musical conventions of the time and to extract unique and remarkable expressions from the musical material in a fashion wholly different from anything available using the major scale.*

In other words, we treat minor scales differently because they are treated differently in the music.

But before we get too far ahead of ourselves, let’s solidify what we know so far, and establish the basics of the relationship between minor scales and minor keys.

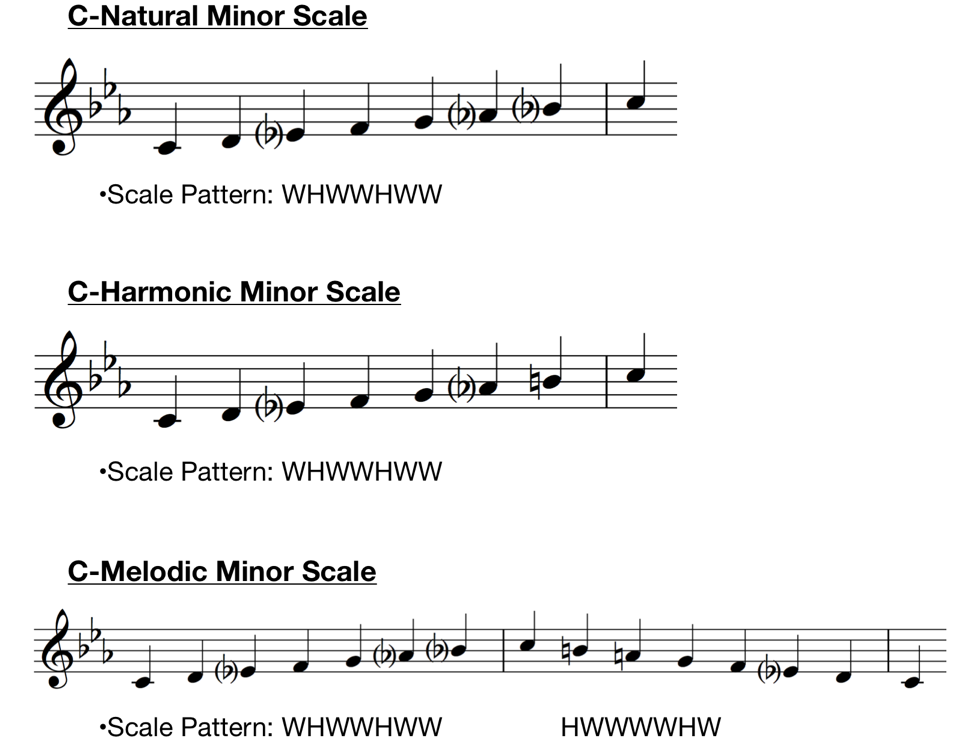

Here again are the three minor scales we know displayed in notation form. We have also included the abbreviated step patterns for each:

* Bach, in particular, is the master of this minor scale manipulation, and much of the complexity of Bach’s later music can be attributed to his rapid shifting between keys and total exploitation of this feature of the minor scale whereby the upper half of it can be so twisted and varied without compromising the tonal scheme.

What you may be noticing by this point is that all of the differences between each version of the minor scale occur towards the “top” of the scale, between different placements of the 6th and 7th scale degrees. The tonic triad, which is what gives us that essential “minor” information in the first place, stays the same.

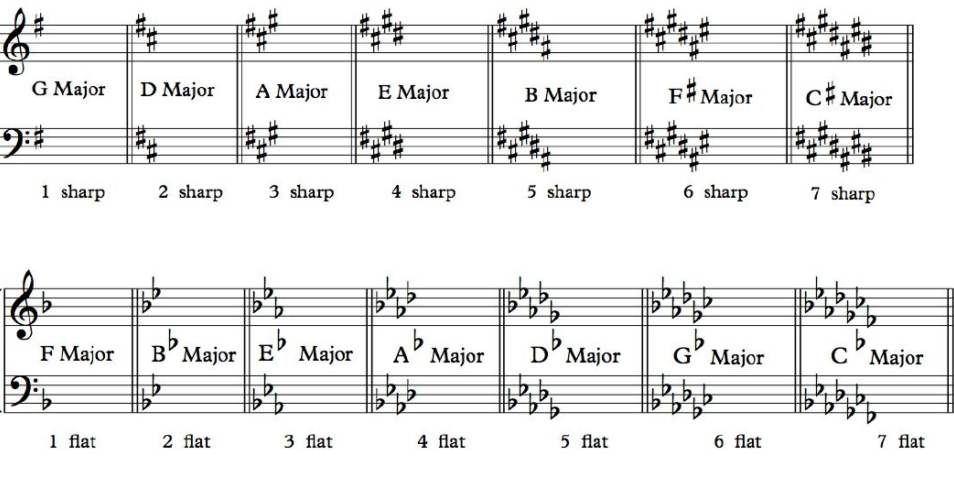

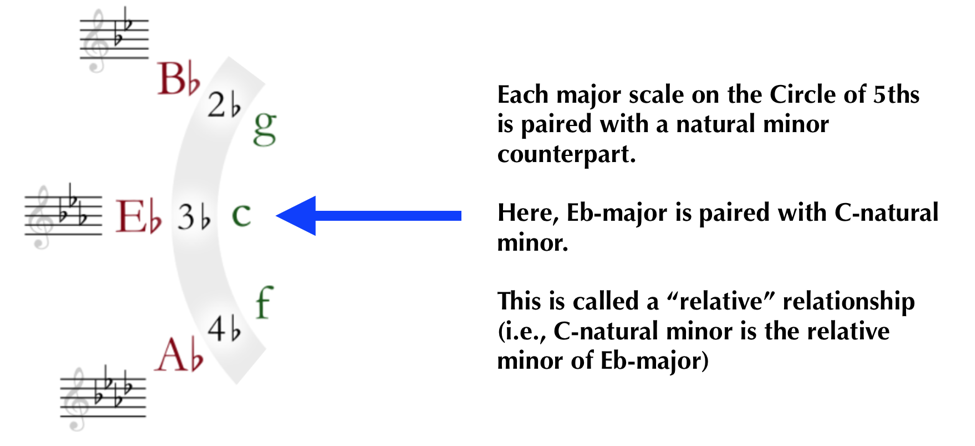

If you’ll recall from the Circle of 5ths, each of our major scales can be paired with a natural minor scale. This natural minor scale can be found by starting on the 6th scale degree and playing the notes of the major scale normally. The same relationship holds true if we’re looking at a natural minor scale, but flipped; the major scale corresponding with the natural minor scale will start on the 3rd degree of that minor scale.

This relative relationship between the two scales is a large part of why we consider the natural minor scale to be the “standard” scale that receives the alterations seen in the harmonic and melodic minor scales.

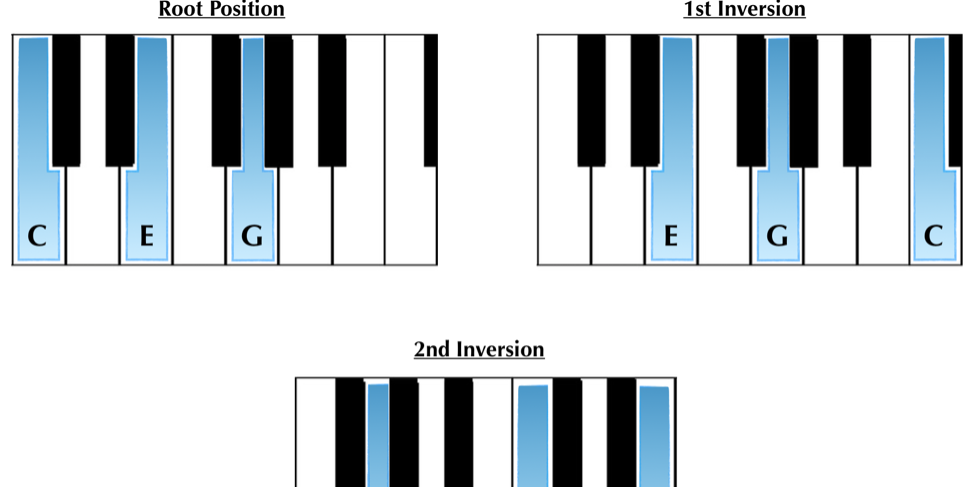

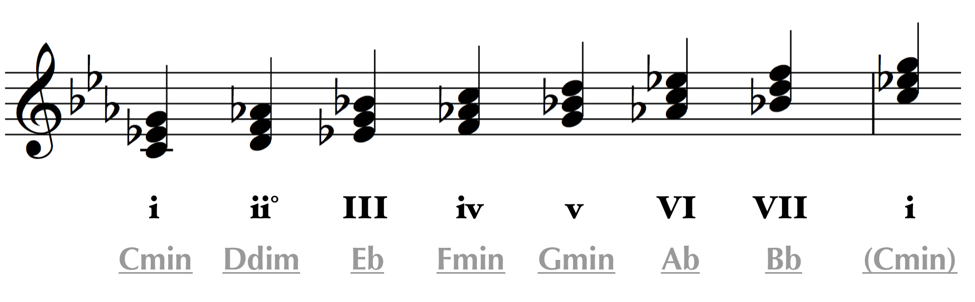

As we did with the major scale, let’s go ahead and build a chord scale using the C-natural minor scale and label the chords we have with both chord abbreviations and Roman numerals. (Remember, an upper-case Roman numeral indicates a major-based chord, while a lower-case Roman numeral indicates a minor-based chord.)

Parentheses have been omitted from our courtesy accidentals here for ease of viewing.

One thing to notice right away is that many of the chord types that we found in major have switched roles in the minor chord scale; our E and A chords, which were minor chords in the major chord scale, are now major chords, while the opposite is true for our C, F, and G chords. Our D chord, which was a simple minor chord in the major chord scale, is now a somewhat more elaborate diminished chord, while the B chord, which was originally diminished, has successfully come out of therapy as a nice happy major chord.

If you’ve not yet played through the chords of the minor chord scale at the piano, go ahead and do so now.

Now play the major chord scale followed by the minor chord scale several times one after the other. Which of the two scales sound “smoother” to you? Does the minor chord scale feel like it keeps that “minor feeling” throughout or at some point does it feel a little in between?

How we alter the chord scale to account for the different sorts of minor scales is an important aspect of working in minor keys, but we have a few more pieces of the puzzle to set in place before we get there.

Bridging the Gap

Let’s remember a few of the elements that go into building and understanding keys.

The first thing that we look for when seeking out the key identity is the scale. As with major keys, the key signature can be used as a shortcut to find the minor scale associated with our minor key, but it’s important to remember, as we just learned, that the key signature will be indicating the natural minor scale only when in a minor key.

Using the Circle of 5ths is one method of figuring out our minor scale from the key signature, as is knowing the scale’s relative relationship with its sibling major scale (i.e., C-minor is the relative minor of Eb-major).

To get the real identity of the key, however, we need to look towards some of the other concepts we’ve learned, namely, figuring out the tonic and searching for our cadences. Remember that the true value and execution of keys lies in functionality, which is the musical state in which all of the musical elements have a relationship with one another, with some relationship hierarchies being more important than others.

While we may be working now in a minor key, we are looking for many of the same functional relationships as we would be in a major key.

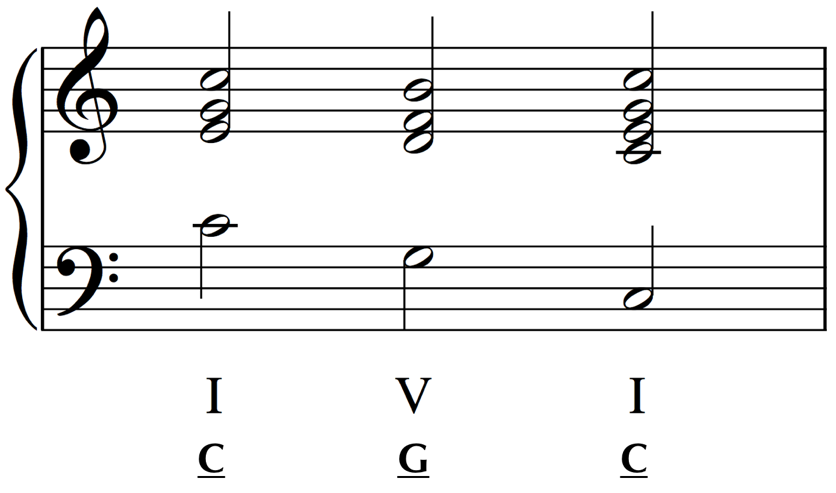

Chief among those relationships is that between the Tonic (I) and Dominant (V) chords.

If you need a reminder about the importance of this particular musical relationship, head back and check out our previous articles in this series, Discovering Keys: Part I and Part II.

Here again is a classic cadence from C Major. Do make sure you play it at the piano and listen closely to the sound of the V chord wanting to go back the to I chord.

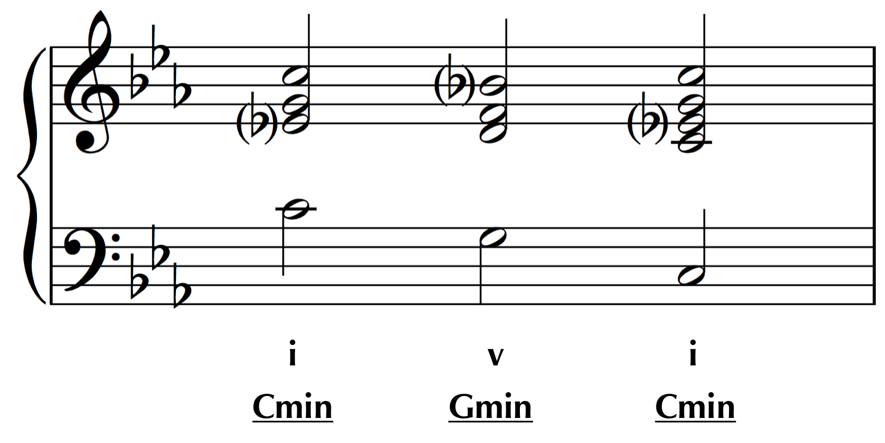

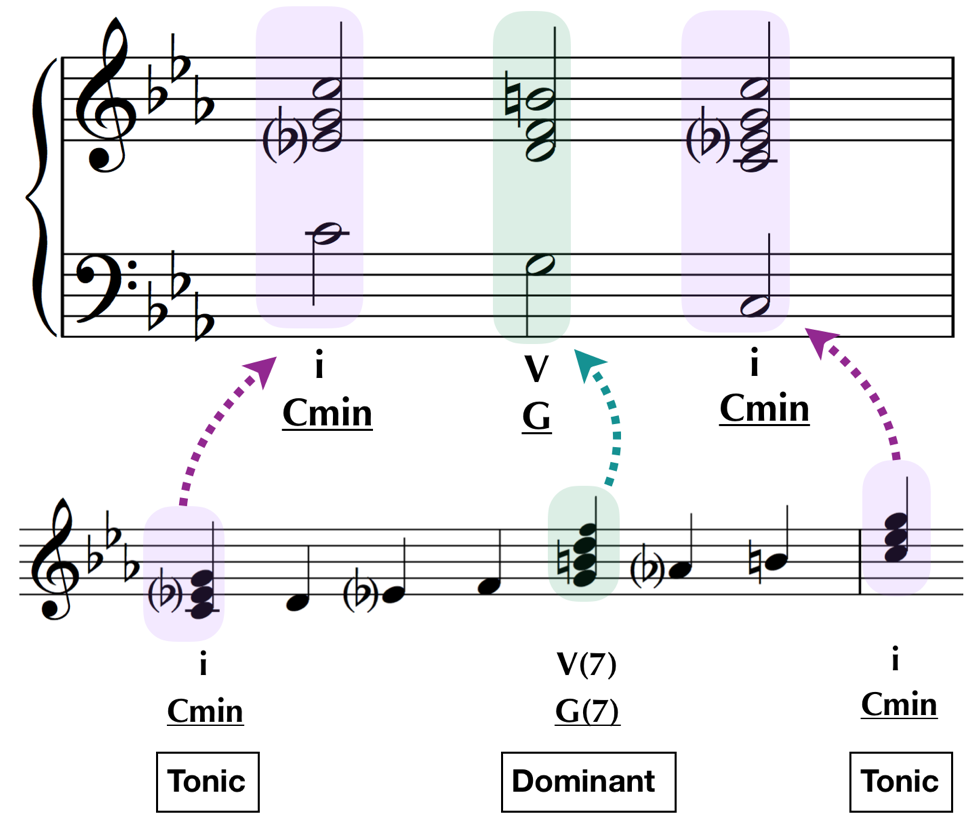

Here now is how this cadence looks and sounds if we translate it directly into C-Minor, using the natural minor scale as the base scale:

Can you feel how the minor v chord doesn’t possess the same need to go back to the i? Play the major version followed by the minor version several times in a row.

Surrounded as we are in modern times by an almost infinite array of musical styles and sounds, it can be a little challenging to acknowledge one sound as feeling drastically more “correct” than another. However, to people living in times past, this minor version of the cadence would have sounded very strange indeed.

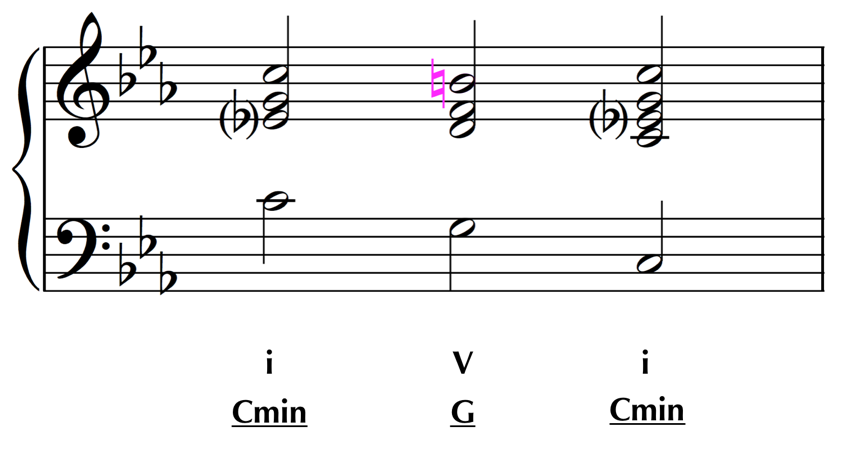

Let’s look at one more version, this time with the minor v chord of the natural minor scale changed back into a major V chord:

Ah, that’s better. Much better, in fact. But why?

Recall that the cadence is usually the most important musical relationship when working with music that uses keys, and the cadence featuring the tonic and dominant chords is the most powerful amongst cadences. To have that relationship, we need to have the characteristics of those chords properly represented, which is a topic we’ll explore more completely in a moment.

Can we still play in keys without cadences? Sure. However, at that point we start to lose the traditional sense of functionality we rely on with keys to give a recognizable identity to the music and start to move into different musical styles. Also, quite frankly, the feel and habits of key-driven music are so ingrained into our sense of musicality that it’s actually challenging to play or create music using keys that does not employ some of the traditional key-based sensibilities. Basically, music in keys that doesn’t use functionality or cadences tends to sound like…well, bad music in keys.

The Sad (but Wonderful) Reality of Minor

To ensure that music in keys sounds and functions the way it should, composers make alterations to the parts of the minor scale that are important to the expression of the cadence and to functionality.

As we just stated, to achieve the powerful momentum of the cadence seen in the previous example, we need the chords to possess the most important characteristics of what we listen for at those cadences.

As it turns out, one of those characteristics reigns supreme over the others — the presence of the raised 7th degree of the scale, or ‘ti’ note.

Just as a reminder, that’s this one:

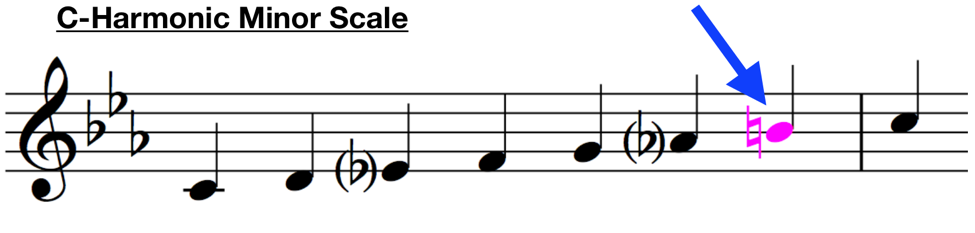

Remember that in the Natural Minor Scale we have flatted 7th (a “te” instead of a “ti”), so in order to get a strong cadence, we need to alter that 7th-scale degree, which results in the Harmonic Minor Scale:

Yep, our harmonic minor scale originated as a fix for the conundrum that is the absence of the raised 7th-scale degree in the natural minor scale.

Raising the 7th in this scale once again builds the Dominant (V) into it, allowing us once again the most important piece of evidence that we’re working in keys:

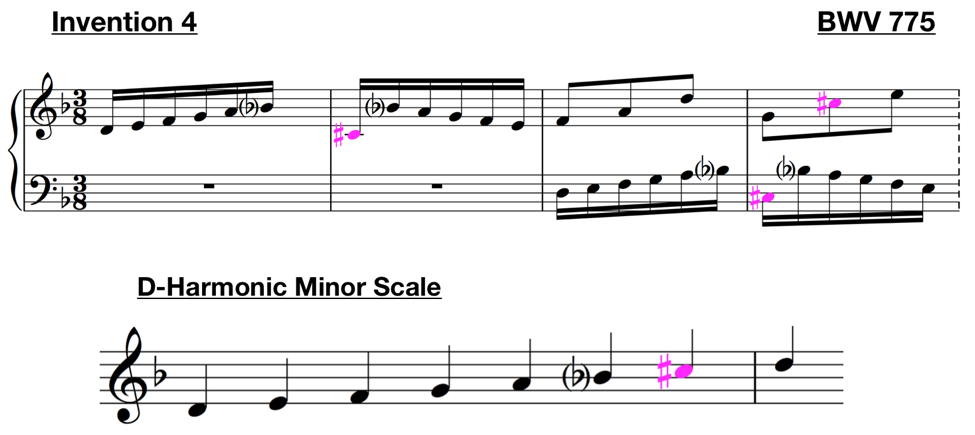

A famous example of the harmonic minor scale in action is the opening of Bach’s fourth Invention, in D-minor.

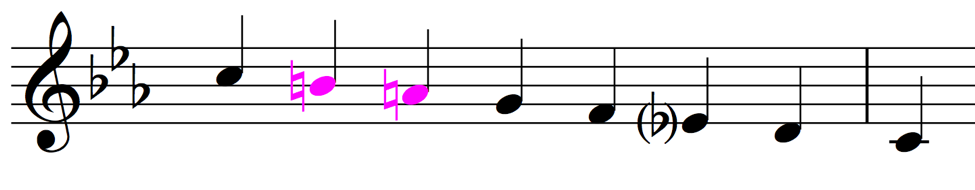

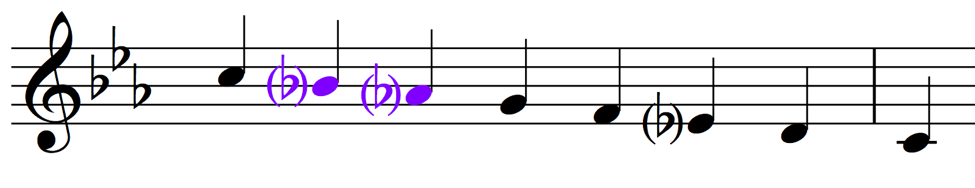

The raised 7th here is highlighted in magenta:

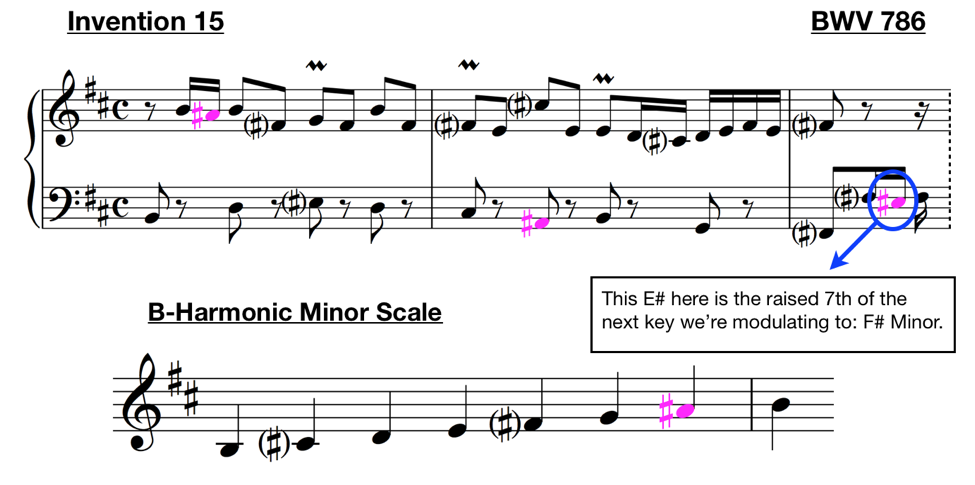

While we’re looking at Bach Inventions, another good example of this can be seen in the Invention in B-Minor:

Here are a couple of links to the pieces above:

For composers of old, however, there were still some issues with the harmonic minor scale. Chief among them are the melodic options this scale offers, which composers from the Baroque through the Romantic found distasteful when not strategically used.

Play the top part of the C-harmonic minor scale back and forth several times:

How would you characterize this sound?

These days we tend to associate it with something inspired by the music of the Middle East, but in the great European hubs of music during the Classical era they did not have such associations, and merely considered it a lesser and undignified sound. (This sound is often maligned for different but related reasons in modern times: for being a stereotypical representation of an “Arabic” sound.)

Notice that neither of the examples from Bach’s Inventions above have this particular feeling to them, even though they’re essentially using the same scale degrees.

To combat this, composers raised the 6th scale degree as well, which affords a much more cohesive sound when traveling up the scale melodically.

Unfortunately, this method does not work so well when traveling down the scale.

Without playing or listening to anything else, go to the piano and play this scale:

Can you feel how jarring it is to come upon the minor 3rd scale degree here? This strangeness stems from your brain’s habit of interpreting this kind of melodic context as being in major. In other words, without any other surrounding musical material present to tell us that we’re in minor, we tend to perceive this descending pattern of scale tones as being a part of the major scale, not the minor scale.

Now play the the natural minor version of the scale downwards:

This likely feels much more, well, natural to your ear.

From here it should be fairly clear where the need for something like the melodic minor scale comes from, and we generally find that most (though not all) classical music from the Baroque through the Romantic features the raised 6th and 7th scale degrees when going up, and the natural, flatted 6th and 7th scale degrees when going down.

Are there exceptions to this rule? Of course. However, most of those exceptions will be composed such that they avoid the highly explicit sounds we heard in some of the examples above.

That said, it became obvious to composers fairly early on that this need to alter the minor scale to achieve the pedigree effects of music in keys afforded a unique opportunity to exhibit some highly expressive sounds that would generally be unavailable (i.e, a bit too strange sounding) in a major key soundscape.

Few composers exploited this opportunity quite like Frederic Chopin (1810—1849), which is why we’ll be taking our final section of this article to look at a few very special chord changes from a very special little piece of his.

The Magical Minor of Chopin

To begin, let’s give this piece a good listen:

In addition to setting the Romantic standard for enormous, challenging pieces of piano music, Chopin is also famed for the brilliant and concise composition of his short pieces. Several of his preludes rank amongst the most famous pieces of music in the world. Contrasting with the satisfying formal execution of sonatas, the freewheeling improvisatory forms of fantasies and the larger scale narratives of dance suites and concertos, many of Chopin’s preludes demonstrate a gem-like quality of composition, focussing on a few essential musical devices with the utmost clarity and a seemingly effortless execution.

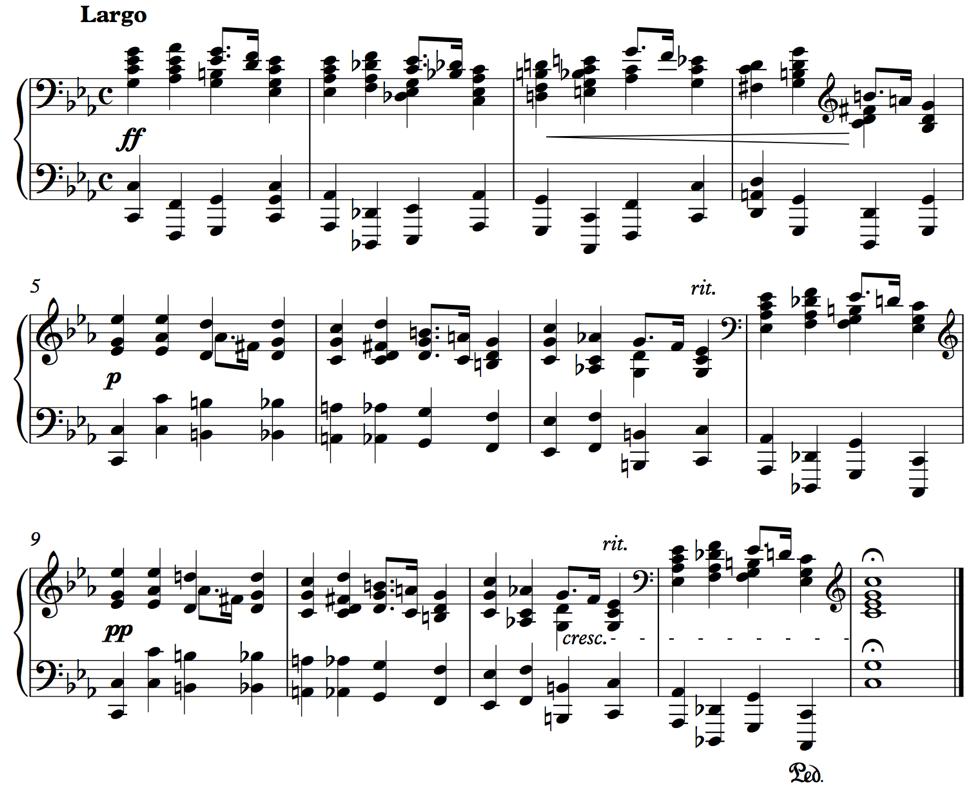

Notice how this piece seems to consist of three sections of very similar material, most of which is delineated simply by altering the dynamics. In fact, while there is some difference between the notes of the first and second sections, the second and third sections are virtually identical, with the only real difference being the designation of piano in the second section and pianissimo in the third. We also encounter some very classic Chopin-esque harmonic choices and some of the great composer’s signature treatment of a simple melody over (or within) a more elaborate accompaniment.

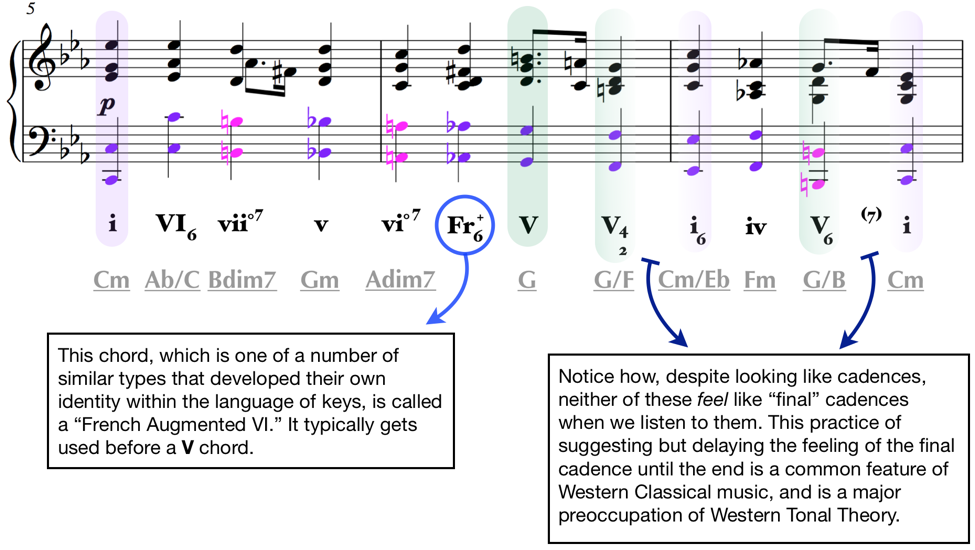

And yet, while there is, despite its brevity, quite a bit to look at in this little piece, we’re after one thing in particular — the descending bass-line that characterizes much of the second and third sections.

Let’s extract one of these from the music:

If you can, try to play through this section.

Don’t worry if this proves a little challenging, what we really want is the descending bass-line. Try to slowly play the left hand octaves by themselves. If this still seems a bit too challenging, you can omit the bottom note and simply play it using the top.

Notice that this passage mostly uses the structure and notes of the C-natural minor scale, with a few important (and, perhaps by now familiar) distinctions.

Thinking back on all the effort we’ve just spent understanding why the upper part of the minor scale needs to be manipulated so much to make minor scales work in terms of keys, does it seem reasonable that we might be able to appropriate those notes and the functions they offer throughout our minor-key musical narrative?

Sure it does:

In more ways than one, the necessity of changing the minor scale to meet our needs when effectively working in keys affords us the altered notes (and their possible harmonies) as viable options for use in the scale in a fashion that is much more similar to the standard notes of the scale than it is to non-scale tones.

Put simply, the raised 6th and 7th degrees are much more like scale tones than like non-scale tones, even when working with the natural minor scale.

Recall that when working in major keys we have three different kinds of non-scale tones: embellishing, modulating, and re-harmonizing. These come into consideration when we are dealing with any tones that are not part of the base scale we are working with in our key.

For minor keys however, we can combine the sounds of the different minor scales such that almost all of the tone alterations we might see in the upper part of the scale can be, in some fashion or another, a normal part of the scale.

The chord scale is a great place to see this in action, as we can see that almost all of the chords we encounter can fit into one or another of the minor scales we use.

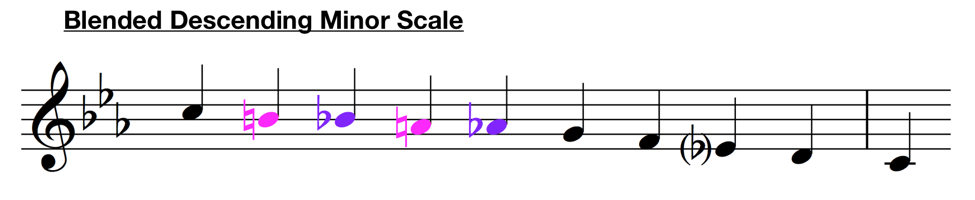

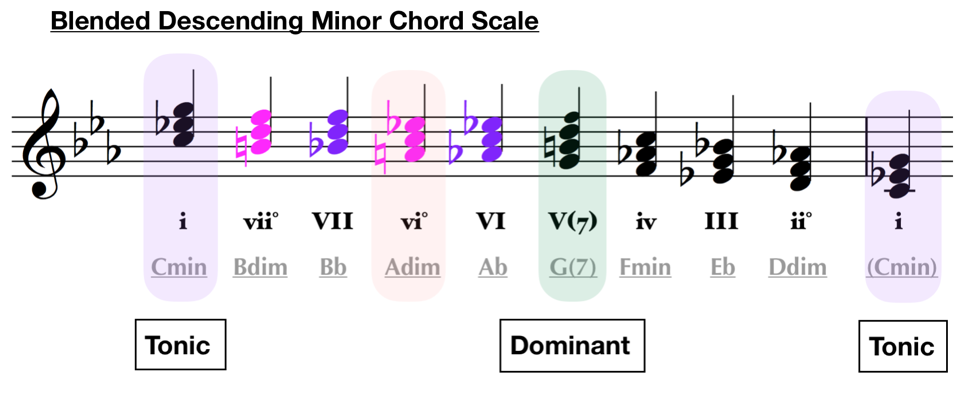

Seeing as how we’re looking at the descending passage in this Chopin prelude, let’s look at a version of the chord scale that blends the notes of all three minor scales in a way that works functionally.

(Once again, we’ve included courtesy accidentals without parentheses for ease of viewing.):

As you can see, we can pretty much fit each chord into some version of the minor scale. The one spot this gets a little thin is with the raised (i.e., natural) 6th degree, highlighted here in the red margin; this diminished chord (or any harmony fit into a minor key featuring that particular note) needs to be treated with care, and will often end up as some sort of non-scale tone re-harmonization or, as in this case, passing harmony. It’s also worth mentioning that this is not the only “blended-functionality” version of the minor chord scale; there are a number of versions and lots of variations that might work in different musical contexts.

That said, the big point here is that this sort of treatment of the major scale would absolutely need to employ non-scale based harmonies to work, and each of those non-scale tone harmonies would be a noticeable step outside the base scale and its attributes. This is not a bad thing, but the ability of a minor key to work within itself gives it some extra flexibility that major keys seem to lack.

Basically, there are more sounds that seem naturally more at home in minor keys than in major keys.

An important thing to know here is that for all of these different sounds to work, they generally need to happen in the guise of certain a template or musical scenario, and they usually don’t demonstrate the verbatim harmonies we see in the chord scale.

This chromatic descending bass-line, using the top notes of the minor scale, is one of those templates. We see this everywhere in music, from Bach to the Beatles. And why not? It’s an awesome sound, and instantly effective at conveying a primo, minor-style message.

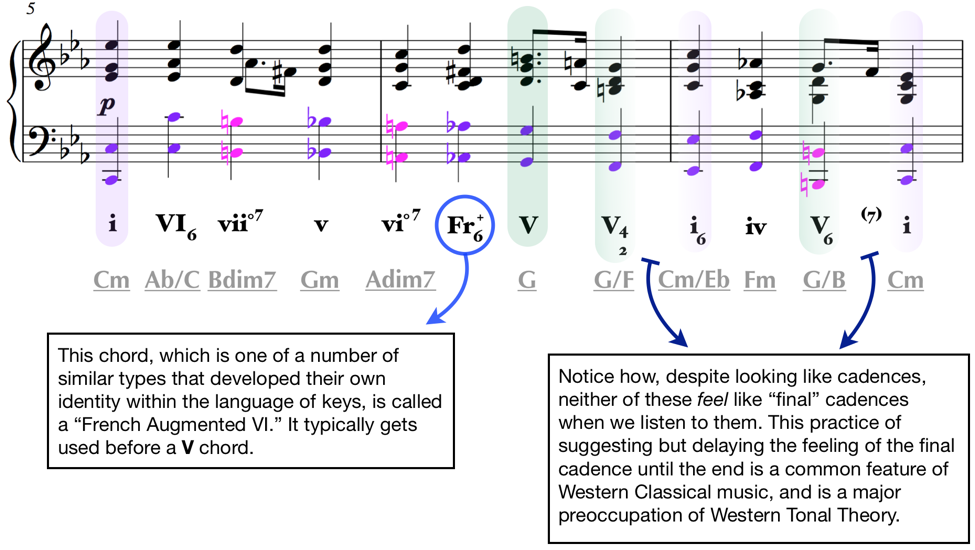

Let’s see how Chopin has treated this harmonically:

For the most part we can see that Chopin has stuck to the natural harmonies of the minor scales, despite generally opting for inversions of chords over straight triads. Notice that there is at least one harmony of pretty alien distinction that we’ve not covered, the description of which really belongs in a full-blown study of Western Tonal Theory. Suffice it to say that, as classical music progressed, some harmonies developed to be entities unto themselves within the key, and many of them like to exist in the preternaturally enriched harmonic soil of minor keys. (Really though, it’s all Beethoven’s fault…)

The relevant info to notice here is that most of what we see in this section falls within the bounds of what we’ve explored throughout this article. Almost everything here we can qualify as being inherently minor, without having to embellish or “borrow” from different keys and scales. It’s as though the identity of a minor key is somehow broader than that of a major key. Indeed, many of the great composers demonstrate their most exceptionally expressive creativity within their minor based works.

Outward

And despite all of that, the most remarkable thing about Chopin’s Prelude No. 20 is how comprehensive it is despite its simplicity. What we have is an indelible little snapshot of “minor-ness,” at once minimalist and encyclopedic. That the piece manages to function as something of a user’s guide to composing down the minor scale as it simultaneously succeeds so well in its own musical expression is a humble testament to the real musical genius of Chopin. It is also a perfect, micro-cosmic example of how much of this “key-theory” can be packed into a few sparsely populated bars.

In our next and final article in this series, Discovering Keys: From Then To Now, we will look further at how the elements of keys were used by some of the great composers in history, how they evolved through time, and how we tend to think of them in modern times. We will look some examples of how jazz musicians think about keys, how keys have been embraced and eschewed by different musical styles and practices, and how we can use our knowledge of keys to enrich our own learning as we move forward with our musical studies.