What are Scales and How Can They Help Us Learn About Keys?

Have you ever had conversation with someone about their bygone days of learning a musical instrument?

Often the conversation begins with them remarking, “You’re taking music lessons? Nice. Yeah, I took some piano lessons when I was younger. I really liked it, but I wasn't really any good. Think I learned Fur Elise and some Mozart and, you know, did scales and stuff…”

It seems we’ve all heard of--or practiced--scales at some point. In terms of learning our instruments, practicing scales serves as an accessible method for improving our technique and increasing the ease with which we can move our hands around our instruments.

And while, yes, scales as dexterity exercises are important for our technical facilities (almost all styles of music use them), they offer an equal and perhaps greater value when considered in a way that we might think of as being, well…linguistic.

Basically, scales contain the core material we use to write the poetry for a given musical moment. Whether it’s Bach elaborating contrapuntal lines, Chopin unleashing flurries of hyper-ornamentation, or John Coltrane blowing sheets of sound, a great deal of music utilizes scales as an infrastructural design component. In other words: scales are blueprints for the notes we will use for a given portion of music. You will almost always be able to reference a scale to help you better understand the notes you’re playing, and (perhaps more importantly for our purposes), the key that you’re playing in.

In this article, we’ll learn about scales with the intent of applying that knowledge to learning about keys as we move forward in this series.

In the Melodic Sense

In a moment we’ll review some of the basic parameters for the construction and naming of scales, but for now, let’s look at a few examples of how we might start to use one of music’s most prevalent features, melody, to help us place our scales within a musical context.

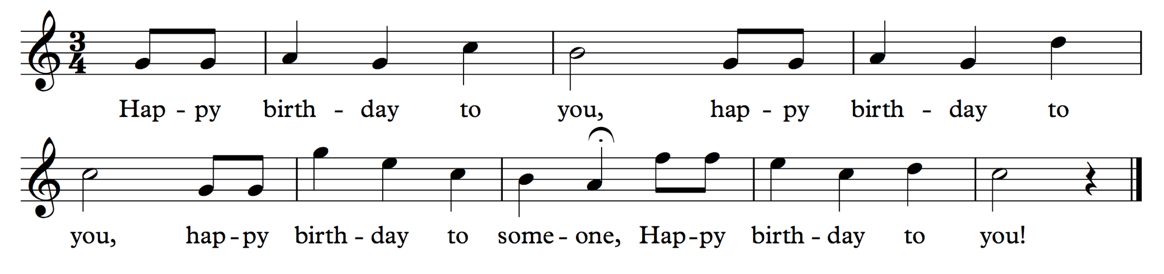

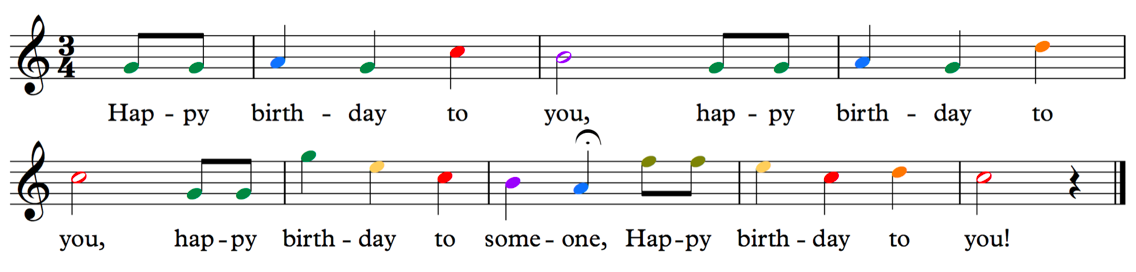

Chances are you’ve heard the following tune. After all, everybody has a birthday…

Feel free to sing or hum this to yourself to get it in your head.

How would you classify this most famous and singable of melodies? What kind of emotional quality does it have? Is it happy or sad?

Most people would probably say it’s a happy song (you know, depending on how old the person may be turning…). So, it’s probably in something major, yes?

Would you say it’s fairly simple or does it seem somewhat complicated?

One thing you’ll probably notice is that this version of the song doesn’t have any accidentals (any sharps or flats), so one thing we definitely know is that, played at the piano, it only uses white keys.

Do we know of any know of any major scales that are played using only white keys?

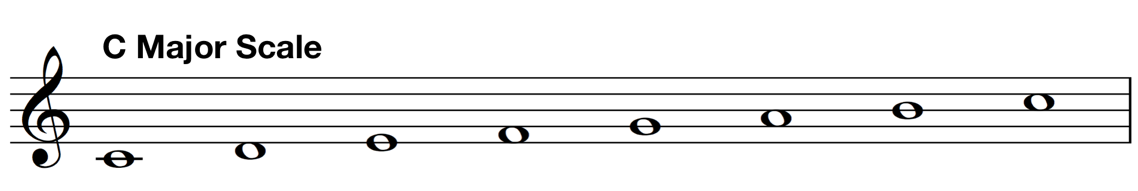

Of course we do:

Even if you have no experience with scales, you’ve very likely played or heard of the C major scale. We’ll be using it quite a bit in this article, but before we get much further, let’s take a quick look at how the notes of the C major scale relate to those of the Happy Birthday song excerpt above.

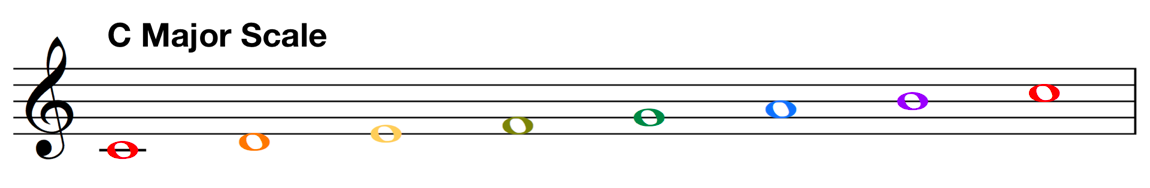

To help with this, let’s give our scale some color:

The colors here are merely meant to help us distinguish between notes and the locations of notes, and are not some secret, advanced analytical technique. As with many things we learn, we are often best served by incorporating already familiar kinds of information into our learning process. In this and many other cases to come throughout this article series our familiar information of choice will be color coding.

Let’s now apply a similar sort of coloration to the “Happy Birthday” example to see if we can identify where the notes of the scale coincide with the notes of the song.

We can see that there are many shared notes between the song and the scale. In fact, as you may have noticed, all the notes of the scale can be found in the song. You may have also noticed that the same colored notes do not fall on the same spot in the stave as in the above scale example, but are still considered scale notes. This is due to what we call the principle of octave equivalence. Essentially, if you play a scale in one register, its notes are to be considered the same when you move it to a higher or lower one—a C major scale is always a C major scale, no matter where on the piano keyboard (or your instrument’s register) you play it.

Using the notes of a scale, however, is not the only parameter we need to consider to determine which scale is being used for a given melody. We are also interested in how those notes are being used. We won’t get into the technicalities of this now, but even without knowing the precise reason for it, your natural sense of musicality should help you know when something's off.

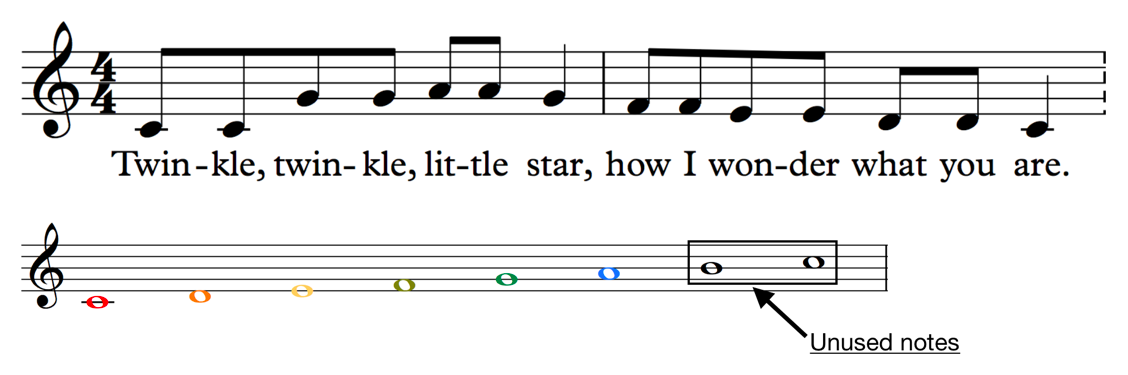

Let’s look at another well known melody to use as an example.

As we can see, “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” uses most of the scale (omitting really only the B), and has a very strong melodic phrasing that first pulls it away from its starting note and then inexorably back.

As we can see, “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” uses most of the scale (omitting really only the B), and has a very strong melodic phrasing that first pulls it away from its starting note and then inexorably back.

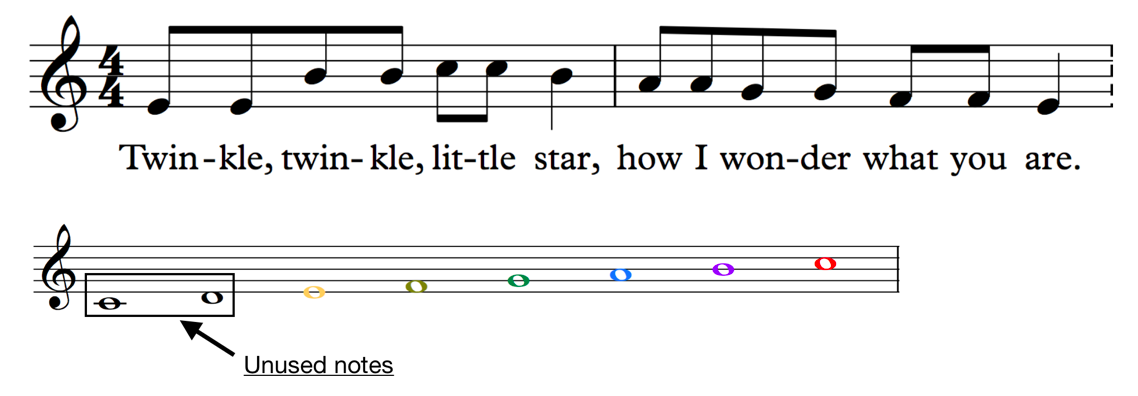

The starting note in this case is C, but what happens if we keep the notes of the C major scale, but change the starting note? Try playing this version at the piano.

Whoo. Does something sound strange? It certainly should. Even though we’re using what look like the notes of the C major scale, I think we can agree, something is not quite right with this rendition… The trouble here is caused by our alteration of the starting note, which has changed the distances between the steps of the scale for the notes of the rest of the melody. We will look at this more in a moment, but let’s look at one more version of this melody.

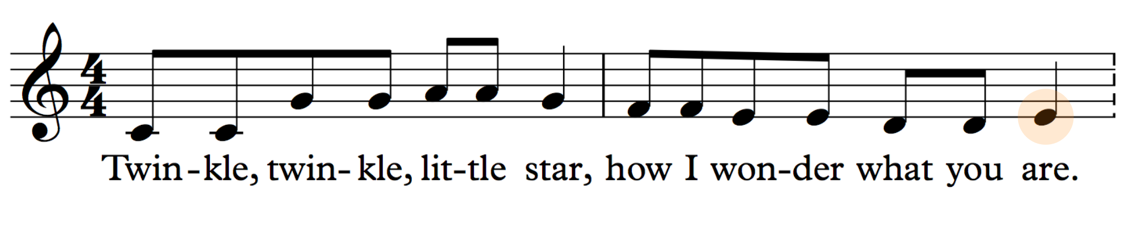

Here our starting note is back to C, but instead of landing back on C, we end on an E. How does this change the feeling of the melody?

In general, this kind of move will make a melody feel less complete, which is desired when building multiple phrases up to a solid resolution. Here we get the feeling that, yes, we need something else (another phrase) to call this melody finished, or simply that it is not a good change and should go back to the way it was. This feeling of melodic ‘completed-ness’ is essential for understanding how scales (and keys) truly work.

Back to Basics: Scales

We’re now going to take a step back and remind ourselves how scales are built and how we name the various parts of them.

Let’s remember that the building-blocks of scales are what we call either steps or 2nds.

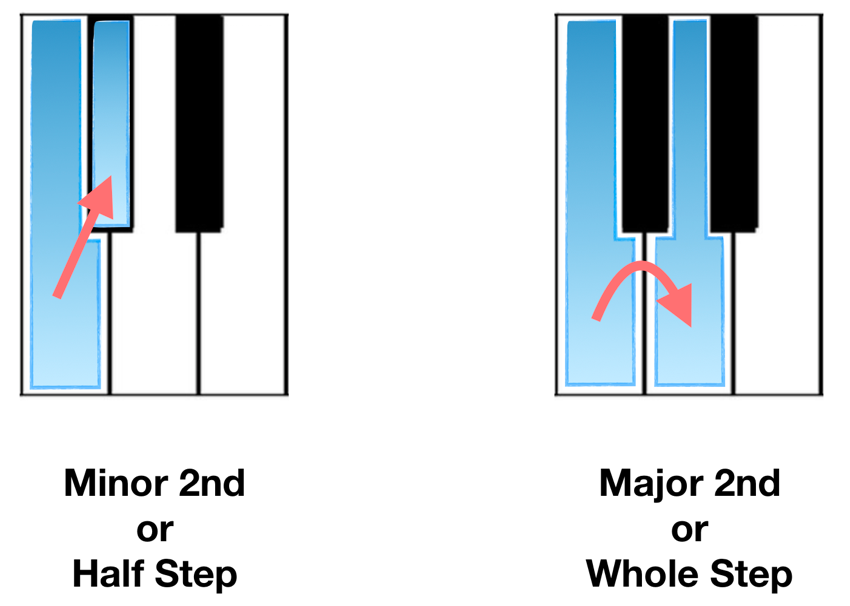

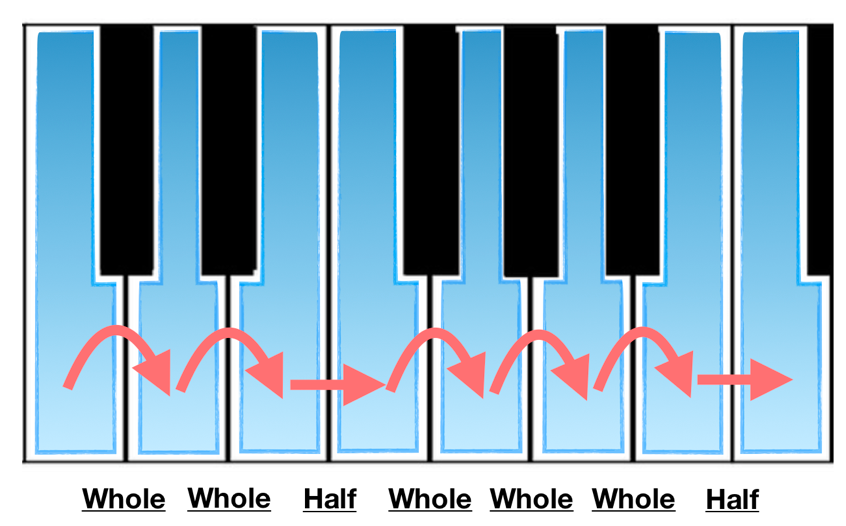

On the piano, steps are the smallest intervals between two notes. Minor 2nds (or half steps) are the smallest; there are no notes, black or white, between the two notes that make up a minor 2nd. Major 2nds (or whole steps) always have only one note between the two notes that make up the interval. Both kinds of steps can be found in numerous places across the keyboard.

Scales are constructed by stringing a sequence of steps together, usually until we reach the same note we started from—either an octave above or an octave below. We almost always tally our scales from the bottom to top, and ‘whole’ and ‘half’ are commonly shortened to ‘W’ and ‘H’ when a sequence is written out.

Let’s look at the C major scale on the piano as an example.

The abbreviated written version of this looks like this:

W-W-H-W-W-W-H, or just WWHWWWH

When the order of steps is not the designated one, we encounter issues like we did with the previous “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” excerpt that started on E instead of C. The sequence of steps for “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” when starting the song on E instead of C is as follows:

HWWWHWW

You may notice that it is ‘backwards’ from the sequence of the C major scale…

We commonly think of scales as the seven-note variety that we encounter most in Western music (also known as heptatonic scales, if you must know…), but there are many kinds of scales from many different places—such as the pentatonic scales featured in many traditional musics of Eastern regions (China, Japan, Thailand, etc.) and of many folk musics around the world.

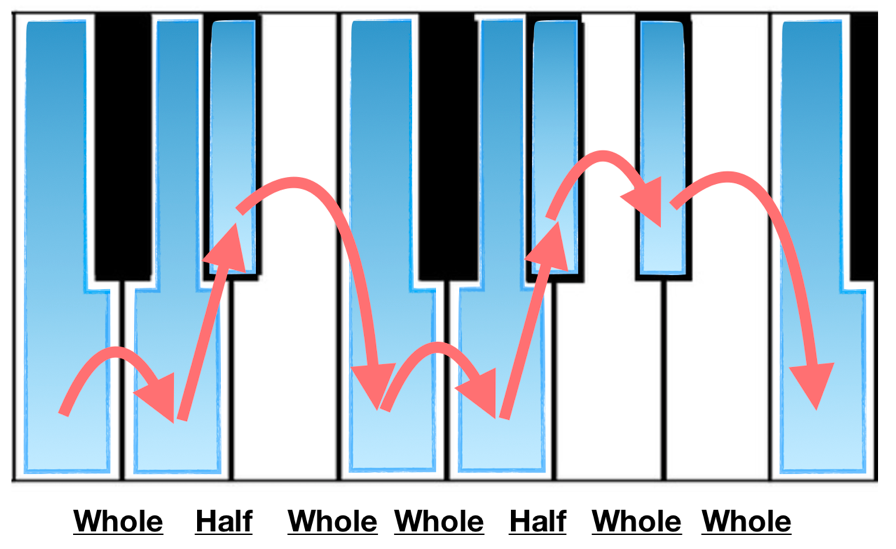

The name most commonly used for the Western seven-note scale is diatonic (e.g., the diatonic scale). We won’t get into the origins of this term, so suffice it to say that a diatonic scale is a seven note sequence of un-altered scale tones (or, ‘natural’ tones), such as a major or minor scale. The different types of diatonic scale we encounter will all have their own sequence of steps. For example, take a look at the diatonic scale on the keyboard below:

WHWWHWW

This is a version of the C minor scale that we call the ‘natural minor’ scale. We’ll reserve further investigations into the different types and constructions of scales until they become more relevant to our understanding of keys, but we do need to know about the naming of scale degrees.

Numerology: Naming Scale Tones

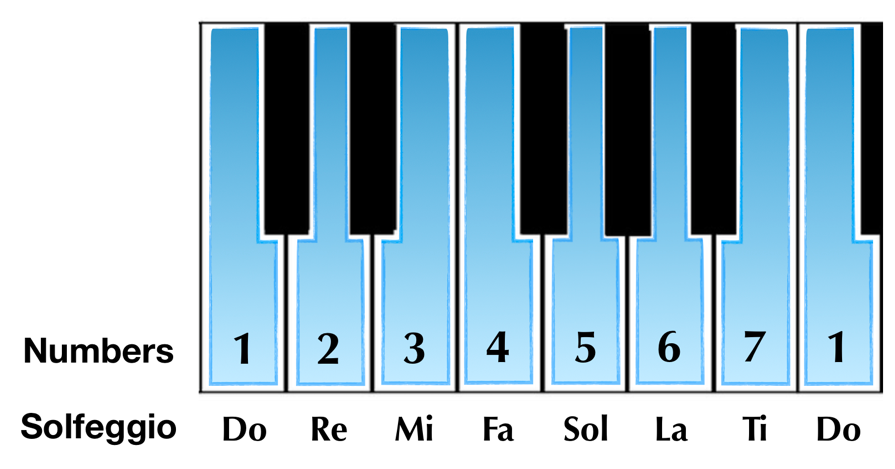

We have two primary methods of naming the notes in a scale: numerically or via the phonetic musical language known as solfeggio. Whichever method we choose, the pitch we start with (which is also the pitch we use to name the scale with) is always the first on the bottom. The scale (by note name) progresses up chronologically until we hit the next octave, at which point the naming pattern restarts.

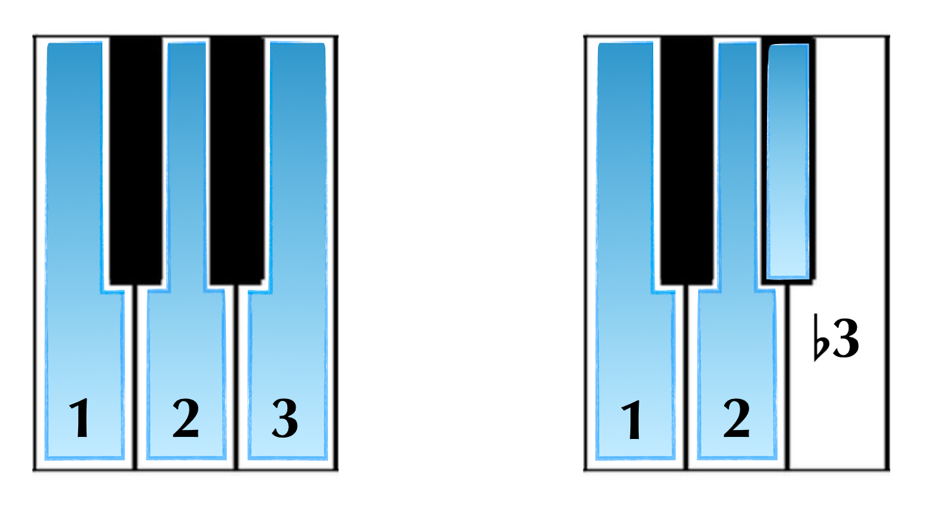

The numerical version of naming scale degrees is fairly straightforward. Any alterations of the ‘white-note’ scale are done simply by applying a sharp or flat to the note. For example:

When named numerically, alterations of the scale are always named by referencing the original note.

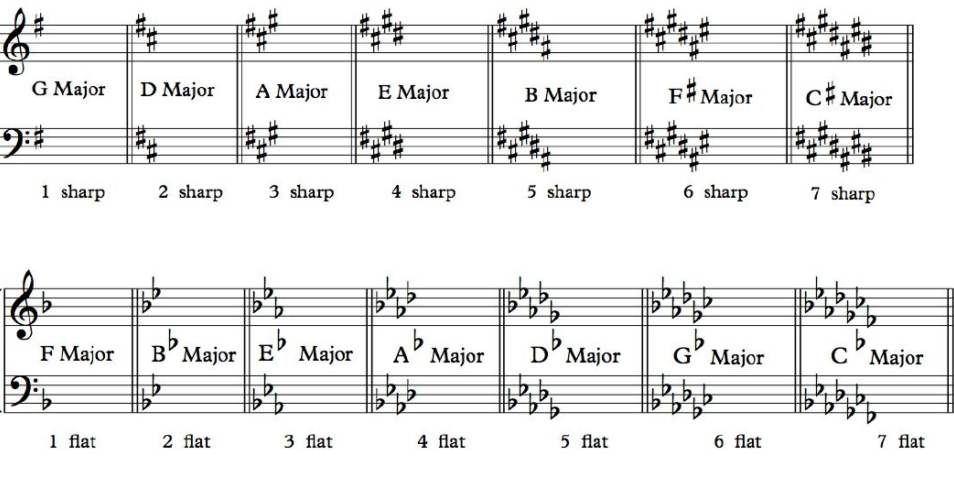

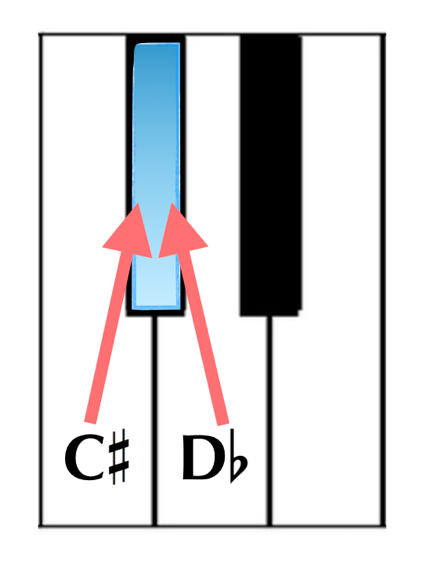

Almost any note can be called by a different name depending on the musical context, but the question usually comes up when referring to something like the example above, when we need to know whether the black note, which has no name on its own, is to be referred to as C-sharp or D-flat. The term for this in music is enharmonic, and we would say that this note is enharmonically equivalent to either name (e.g., C# is enharmonically equivalent to Db). The reasons we choose to name a note one way instead of another depends on how we’re thinking of the scale as a whole. We will explore this further when we delve deeper into the theoretical structure of keys in our final article of this series: Discovering Keys: From Then to Now. What we really want to grasp for now are the core components of a scale and how we think about them.

Our other method of referring to scale notes, solfeggio, is an ancient manner of assigning syllables to the identities of notes. This practice, known as solmization, affords what many think is a more musical (and therefore more effective) approach to note naming. Those trained in solfeggio (which is also known as solfège) memorize the relationships of the notes to one another through the syllables. This is not to say that someone learning numerically cannot achieve this ‘sense of the scale,’ but that the specific learning process of solfège is geared towards that understanding.

This article is not meant to be a solfège tutorial, however for those readers who are curious but not already familiar, try singing a C major scale using solfège syllables. You may be familiar with the popular song from the musical, ‘The Sound of Music’ that is built around going up the scale in solfeggio: ‘Do, a deer, a female deer. Re, a drop of golden suuuun…’.

Now try singing this sequence of syllables, using C as ‘Do’:

Do-Re-Mi

Mi-Re-Do

Do-Mi-Do

Mi-Re-Do

Do-Re-Mi-Fa-Sol

Sol-Fa-Mi-Re-Do

Sol-Do

Do-Sol-Do

Did you start to feel like you were getting to know the notes by their syllables? If not, don’t worry, it can take a bit of training to get the hang of it.

One last thing to know about naming scale notes through solfeggio before we move on: unlike with numerical naming, in solfeggio we actually have distinct syllables for each altered note. These syllables generally have some association with the originals, but are certainly more different than, for example, simple stating the note name with a ‘flat’ or ‘sharp’.

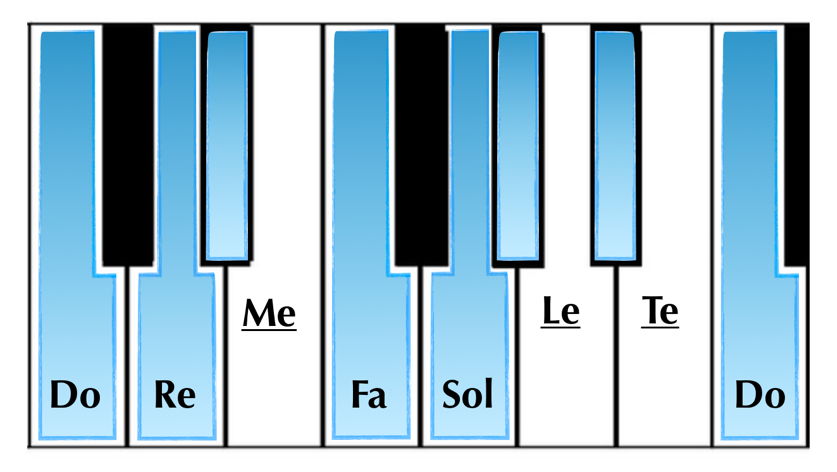

Let’s look at the C minor scale once more for a quick example.

Notice here how the syllables of the lowered 3rd, 6th, and 7th scale degrees are altered into Me, Le, and Te, instead of Mi, La, and Ti from the original major scale solfège. There are many such variants based on whether the melody is rising or falling, and what particular school of solfeggio is being used. These variations for the minor scale will be discussed in more detail in our Discovering Keys: The Minor Keys article. For the rest of this article, we will be focusing on the Major Scale.

Musical Scales and the Mighty Tonic

Our preoccupation here with the naming of scale degrees pertains to our ultimate goal of understanding keys in two ways. First, it is crucial to understand that scales are built in sequence from a starting note (the 1 or ‘do’ note), and that the identity of our scales is governed by the relationships of all the other notes in the scale to that first note. Secondly, our ability to analyze melodic relationships combined with our understanding of scale degrees will allow us to much more easily think of melodies as existing in the scale of a particular key.

Let’s look at a couple of musical examples to help support this.

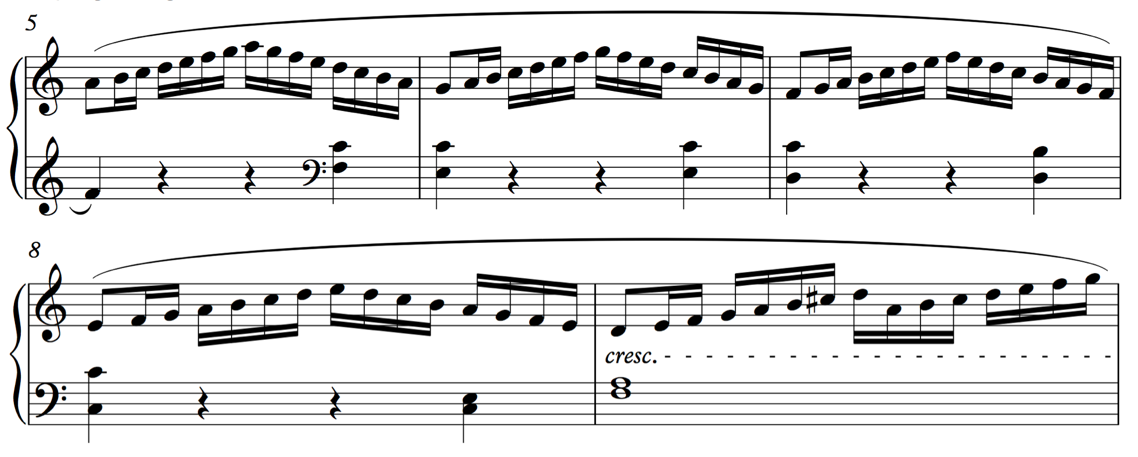

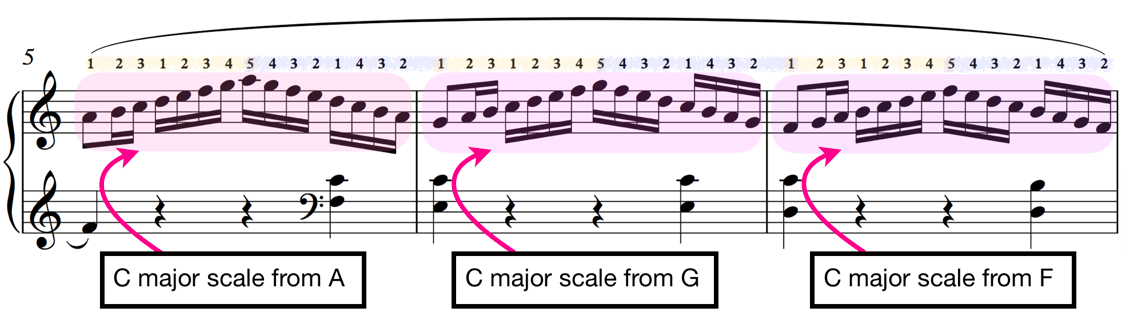

In the first article of this series, we looked at the beginning of Mozart’s Sonata No. 16 in C major, K. 545. In that example there is a section in which the right hand must navigate a sweeping string of 16th note scales.

This can be a little alarming to look at for a piano student still fairly new to the instrument; however, if we’re able to consider the scales as simply versions of the C major scale (and if we’re able to work with the most effective fingering), the passage becomes almost easy, especially if we’ve been doing any sort of scale practice.

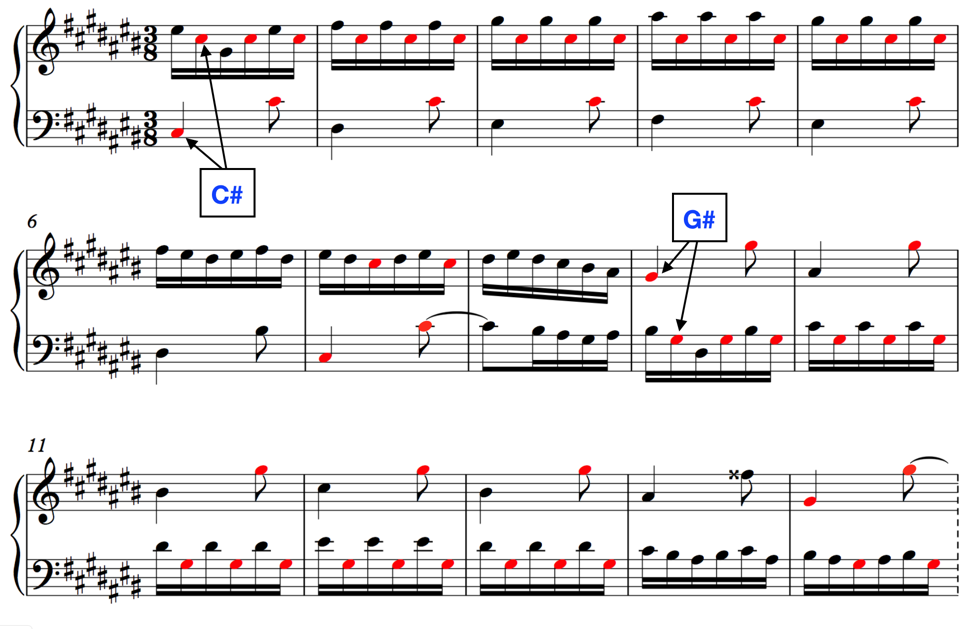

Similarly, once we have enough of a familiarity with scales, their presence (even when hidden within a phrase or line) can make the music more decipherable. Take this next example, the famed Prelude No. 3 in C# Major from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1:

Kinda scary looking, right? I mean, seriously, how many sharps are in that key signature?… Certainly it seems improbable that such an effort-intensive looking manuscript could be associated with such an effortless and effervescent sounding piece of music. But that’s Bach for you!

While this is certainly not what we might consider an easy piece of music (easy in the “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” sense, that is), it becomes much more easy to interpret once we apply some knowledge of scales, and perhaps more importantly, a bit of understanding of the concept of tonic. This brings us to our final point for this article.

On the most basic level, the tonic is the first note (the ‘1’, or ‘Do’ note) of the seven-note scale that we most frequently encounter in the Western music. The term is derived from the analytical practices of Western tonal theory, which we will touch on throughout this series. Fortunately, the meaning and value of the tonic is something that we can access without delving into those murky theoretical waters, which is good, as it’s one of the more important and useful concepts in musical thinking.

The tonic is the ‘home-note,’ the hand that launches the yo-yo, the ground beyond which the sun rises and falls… Whatever your preferred metaphor, it’s important to consider that the concept of the tonic is, first and foremost, a phenomenon derived from Western classical music based on a musical feeling, rather than a theory. We interpret this feeling analytically later, but for now think of the tonic as the feeling of home, the place that we start from at the beginning of a piece, and return to at the end.

Have you ever wondered why certain parts of music are more ‘satisfying’ than others? Why cadences can be so relieving? Why the chorus of a pop song is so good? Why the music of Schoenberg and Webern and Stockhausen is so…work intensive to listen to? It all comes back to our primal need for the return to the ‘home-note,’ to the tonic. It is, of course, plenty more complicated than that, and yet, in many ways, not really…

For now, let’s apply a little of all of the above to see if we can shed some colorful light on that Bach prelude.

First, give the beginning of the piece another listen. Now give it another one. Now, if you have a piano or any other instrument available, see if you can find a single note that seems to sound ok when played together with the first 6 or 7 bars of the piece. You could even try singing for it, but you’ll want to be able to name that note shortly.

Are there any notes that seem to work better than the others? Try doing it now with bars 9 through 15. Are the notes you’re coming up with changing? Keep at this a few more times until you feel like you have some note options for both sections.

In doing this you may have noticed that a single note seems to ‘work’ better than any of the others. It may simply sound the best or it may seem like it’s a note around which everything else can happen without too much interference. You may have also noticed that, there is a note that constantly repeats amidst the movement of the other notes, and that this note changes from one section to the other:

C# for the first section, G# for the second. If you’d hadn’t decided on these as your notes when you were playing along before, try using them now.

Notice that we seem to lose these notes a bit in bars 6-8 and bars 14-15, at least with regards to the kind of stability they seemed to have in the preceding measures. These are the areas of greatest (or, perhaps more accurately, quickest) change, and they serve as transition zones from one core area to the next.

Let’s call the C# the tonic (the ‘1’ or ‘Do’ note) for the first section, and G# the tonic for the second, and see what we come up with scale-wise.

We can now see the color-coded scale degrees rising and falling around the grounding repetition of the tonic for both scales (in red for both sections). Notice how there are two instances of this for each section, one in either stave, and that they switch roles when the sections change (the figure that was on the bottom is now on the top stave and visa versa). The coloration here is meant to help visualize the pure forms of the scales as they are represented in the phrase construction, and we need not know the theoretical details to feel when the scale changes.

Try this now: Playing along with a recording of this piece, see if you can start a C# major scale on the first beat of the first measure and play up one scale degree for every measure (C# on measure 1, D# on measure 2, E# on measure 3, etc.)

Notice anything? The scale is completed on measure 7, where our purple ‘7’ or ‘Ti’ notes indirectly ‘resolve’ themselves to the tonic, just as though we were playing a normal scale! Of course, Bach couldn’t simply write out a normal scale and call it a prelude (though if anyone could have…), he had to obscure and embellish, to enrich the scale with multiple lines and jaunty rhythms. That said, the piece is much more friendly to think about if we can break down sections like these into embellished scales rising and falling over and under an immobile tonic.

And even so, we don't need to get anywhere near as complicated as this to feel the sense of home offered by the tonic. Venture back to the excerpts at the beginning of the article and consider them in this light; what are the tonics of “Happy Birthday” and “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star”?

With the right kind of practice, you’ll be able to identify the sense of tonic in lots of music that relies on it for structure and identity. In fact, part of the development of writing pieces in multiple keys (and indeed, one of the greatest preoccupations of the evolution of Western Classical music) has been the desire of composers to delay that return to the tonic in the attempt to increase the final satisfaction of the tonic return.

Extending out from the tonic we have our scales, and through an understanding of them both we can truly begin to effectively think about keys.

In the next article we will give a similar treatment to chords, and see how we can apply our learning about them to our goal of understanding keys.