Practicing scales is one of the most commonly encountered topics when exploring ways to learn the piano.

There are good reasons for this; practicing scales not only teaches you how to navigate the keyboard, but also teaches you about some of the key, foundational elements of musical thinking. The notes within scales are used in composition to determine how the melody and harmony work together. Knowing more about scales and the notes they contain will make it easier to understand how music works, and easier to learn pieces.

However, before you can achieve that level of understanding, you need to become familiar with what scales are, and what kinds of scales can be learned.

What are scales?

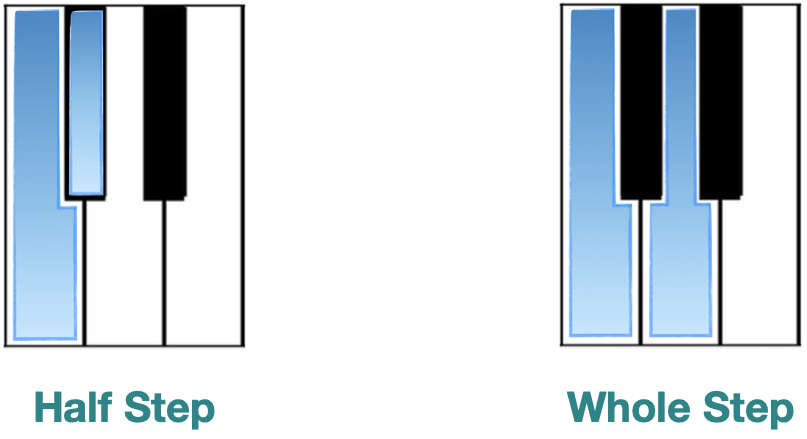

Scales are collections of notes that usually span from one note to another note of the same type up or down an octave, encompassing a series of notes in between. For basic, diatonic (7-note) western scales, the notes within a scale are separated by the smallest distances between notes: steps (or 2nds). We have two kinds of steps we consider: whole steps and half steps.

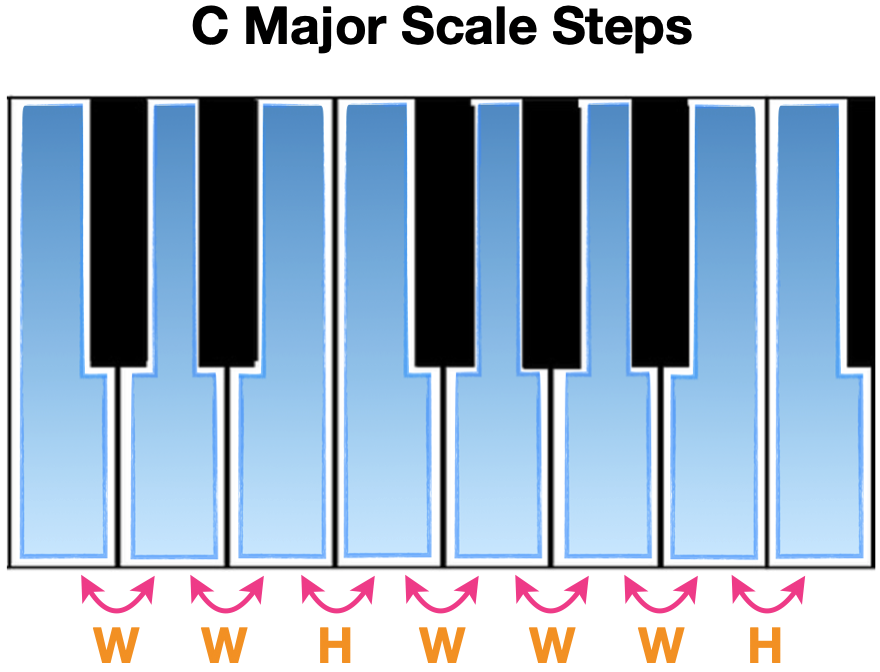

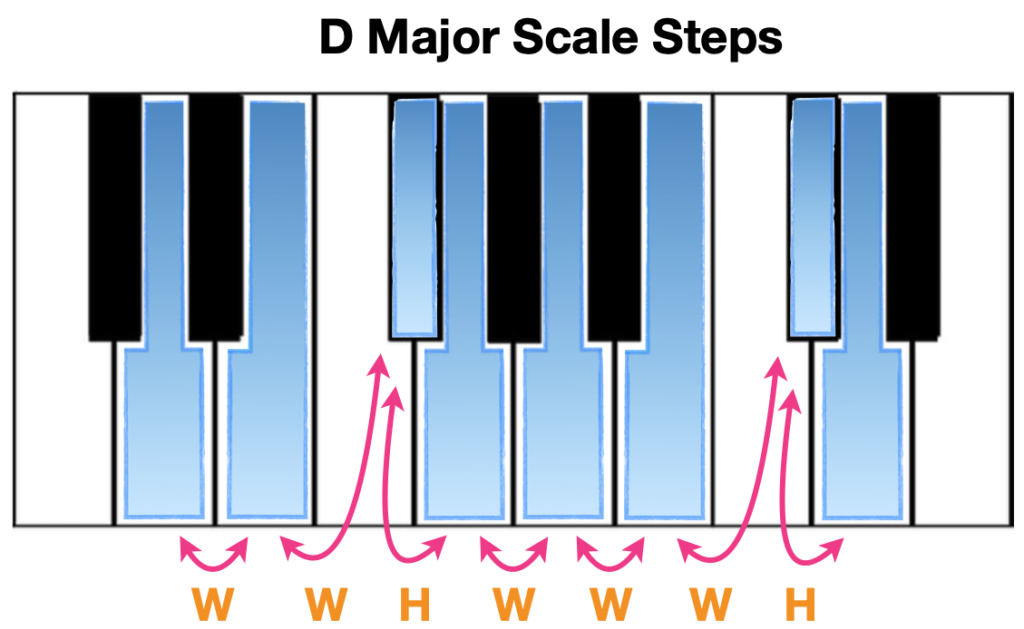

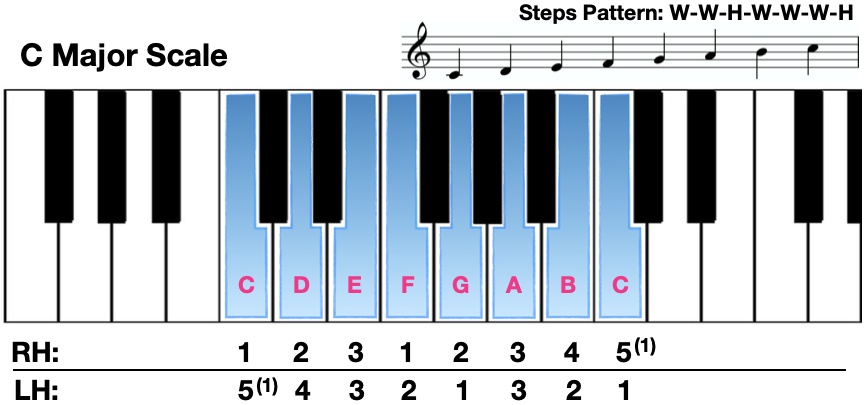

We combine a string of steps into a regular steps pattern that gives us the sound of scale we want: For example, a major scale starting on C uses this steps pattern: whole-whole-half-whole-whole-whole-half (abbreviated: W-W-H-W-W-W-H).

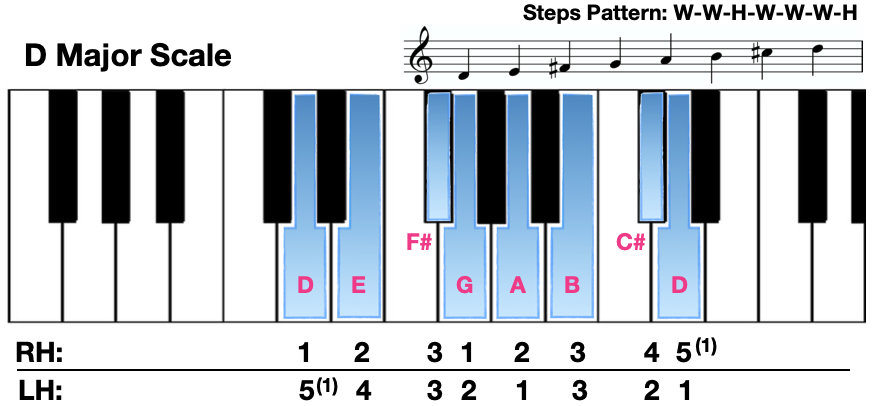

All major scales will use the same combination of steps to achieve their sound, even if that means changing white notes to black notes. For example, you can see that if we start a major scale pattern on D, we have to use a couple of black notes to get the scale pattern correct:

Different types of scales will use different steps patterns.

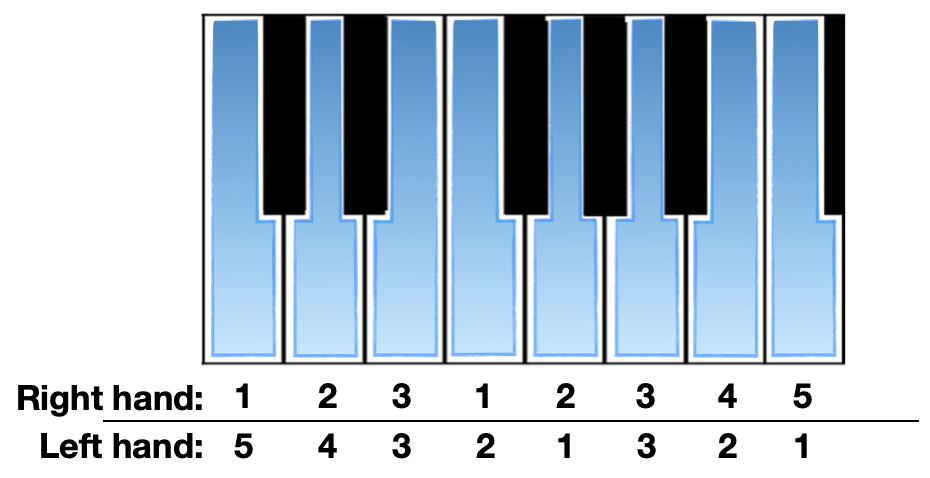

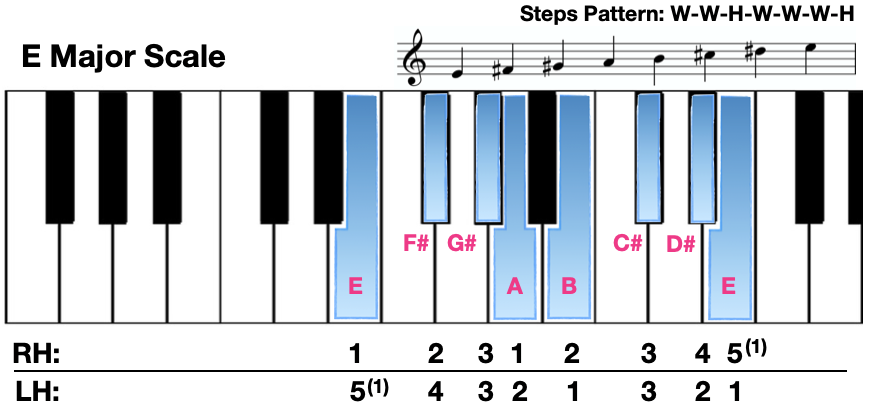

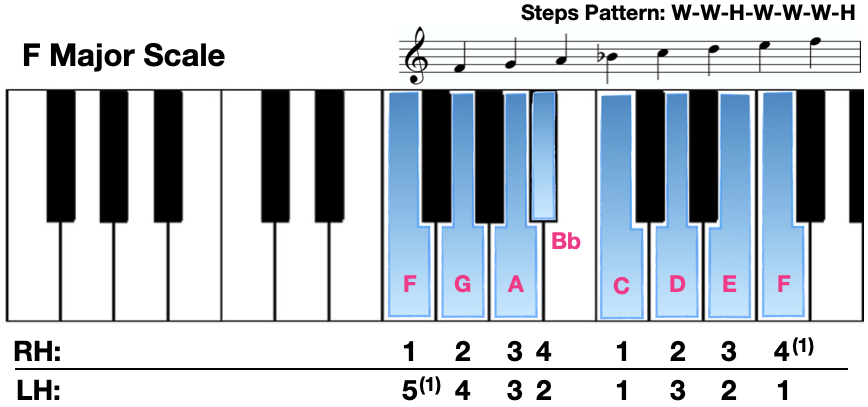

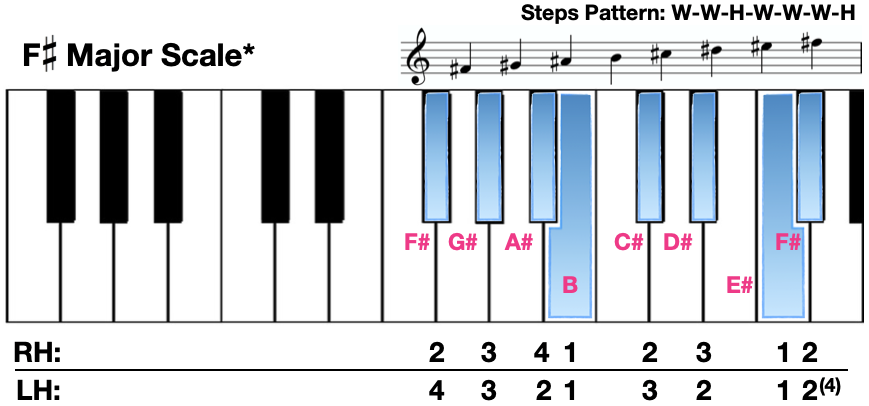

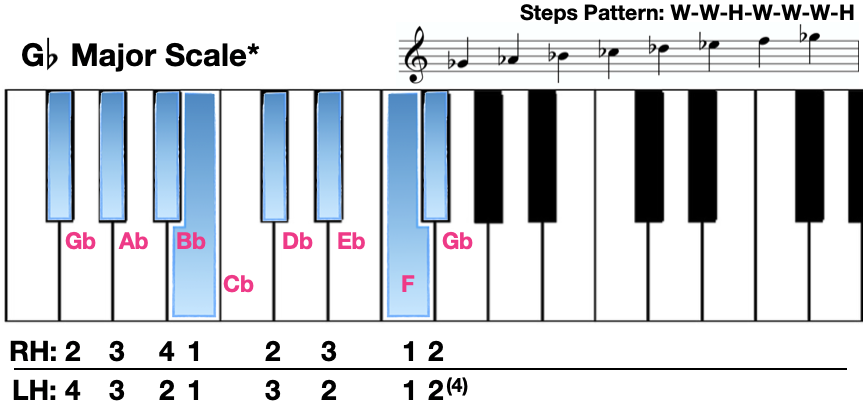

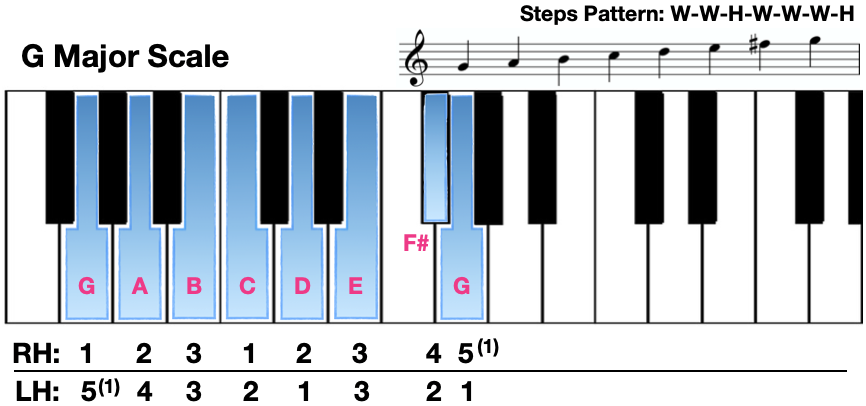

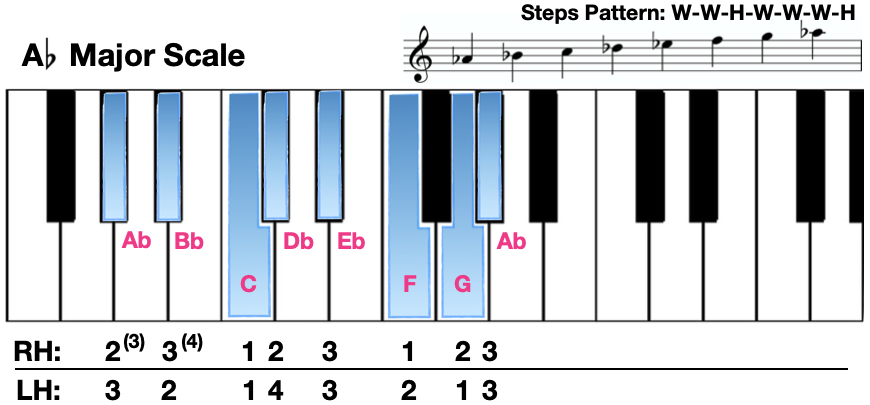

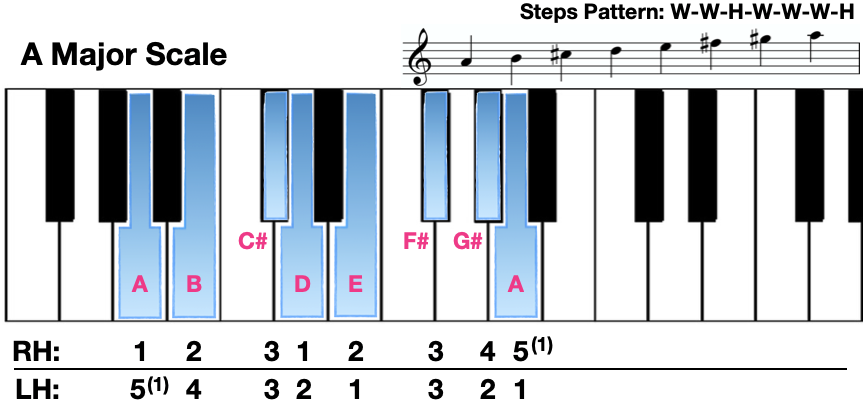

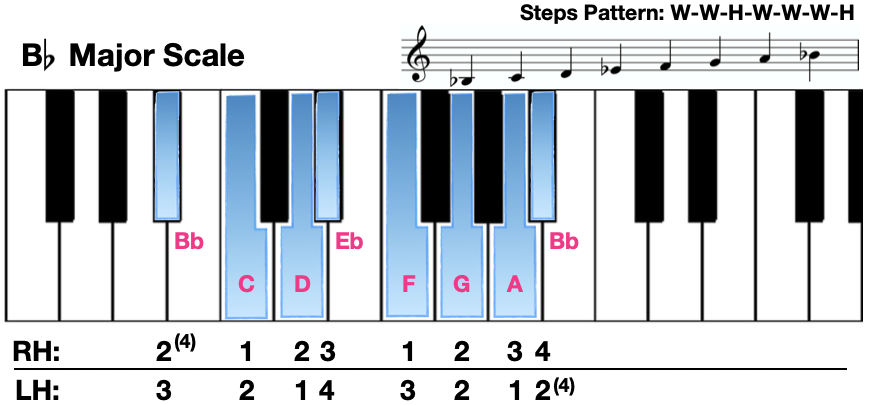

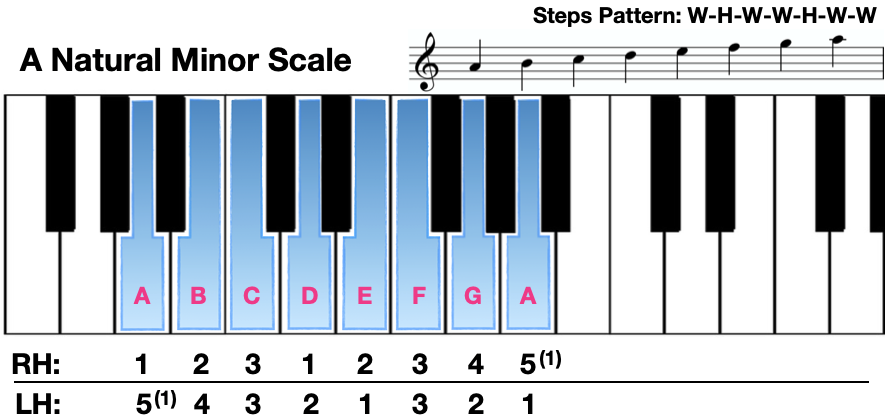

When playing scales at the piano, it’s important to know the fingers you’ll be using to play the notes. We label the notes of the scale with finger numbers to help with this:

Different types of scales will use different steps patterns.

As you learn scales, you’ll start to become more familiar with the types of notes they contain, and will eventually be able to memorize those notes and play the scale without having to think about them. For more on how to read music notation, check out our guide here.

You’ll also learn to view notated scales using key signatures, instead of with each accidental placed before the note. For more about key signatures, check out this article.

How to use this article

In this article we’ll provide a catalog of all major and natural minor scales as they appear on the piano. We’ll show you what notes are in them, and which fingers you need to use to play them in either hand. We’ll also provide you with the pattern of “steps” (or 2nds) that each kind of scale uses to produce its characteristic sound.

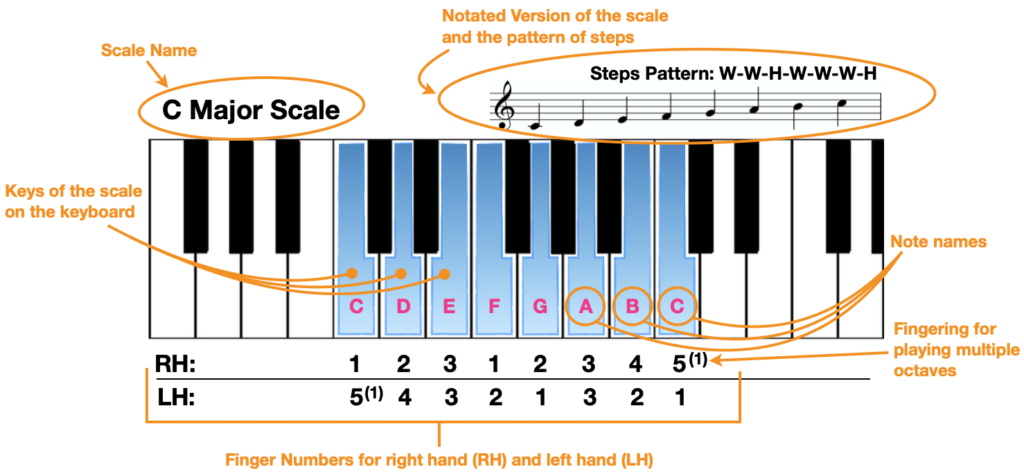

Here is an example of one of the scale diagrams found in this article, with labels explaining its parts:

Note names for notes that are sharped or flatted are seen next to the notes they're indicating, on keys that have to move when they're added (for example, an "F#" will be next to the note itself, on the note F, while a "Gb" will be on the opposite side, on G).

An important note: While the scales shown are only one octave in length, scales are often played for more than one octave. The finger numbers in parentheses indicate which fingers you would use if you were to continue the scale up or down more octaves.

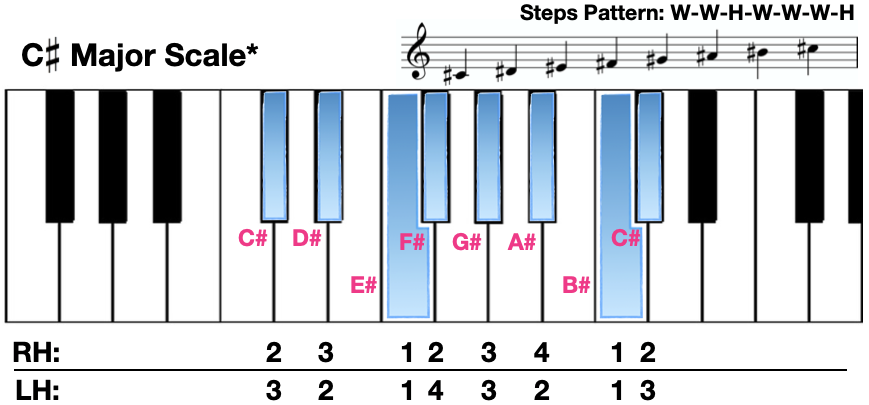

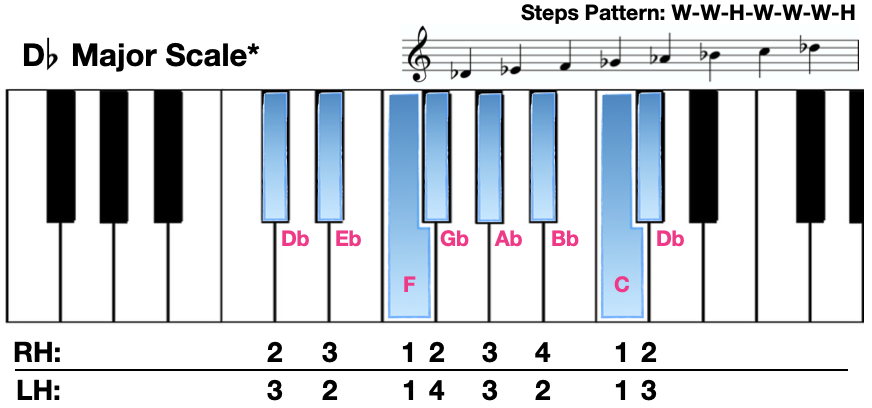

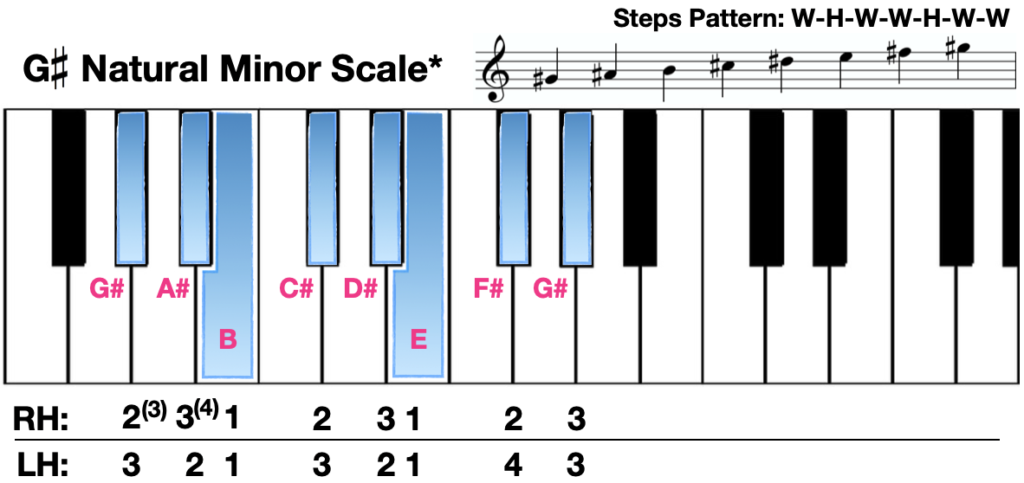

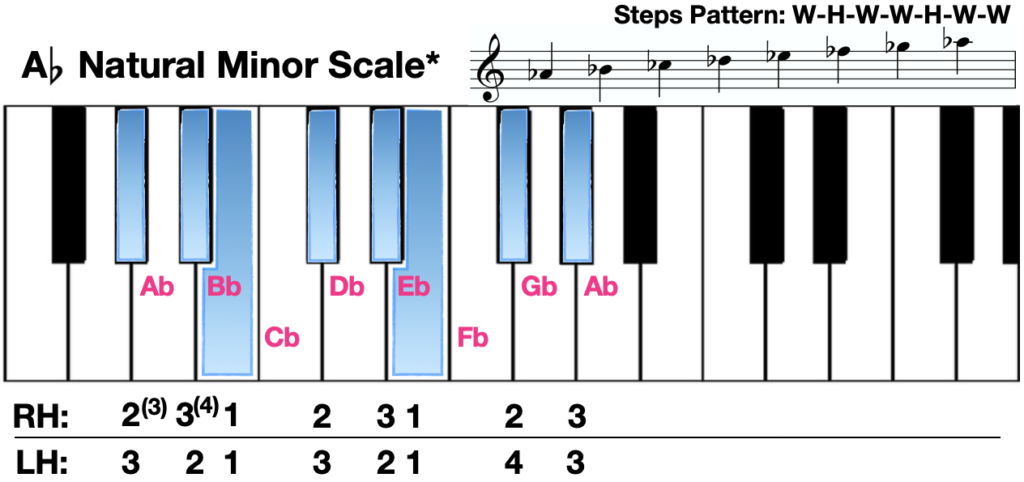

Lastly, scales marked with an asterisk (*) have an enharmonic equivalent. We'll tell you more about that when we get to one.

For more on how to practice scales, check out this article. We also have video lessons on how to play scales at libertyparkmusic.com!

Major Scales

The next two scales use the same notes, but have different names for those notes depending on the musical context. We say that they are enharmonically equivalent, or that they use different note names for the same notes.

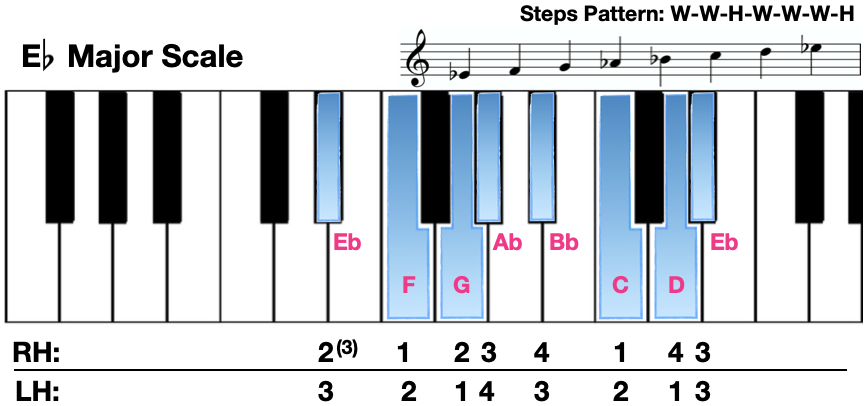

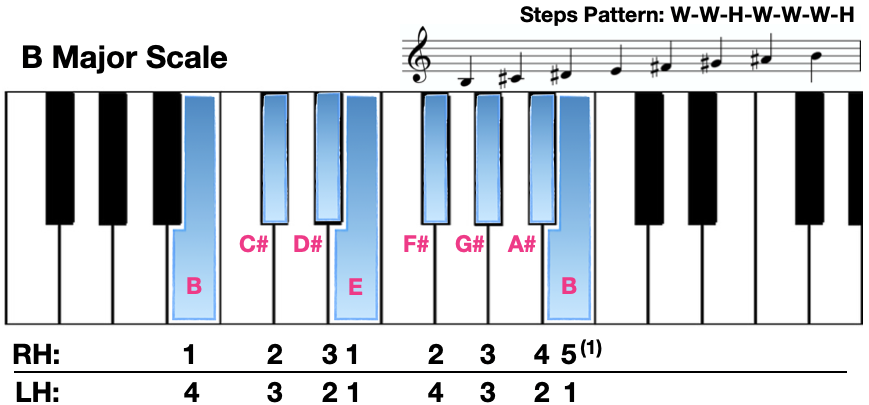

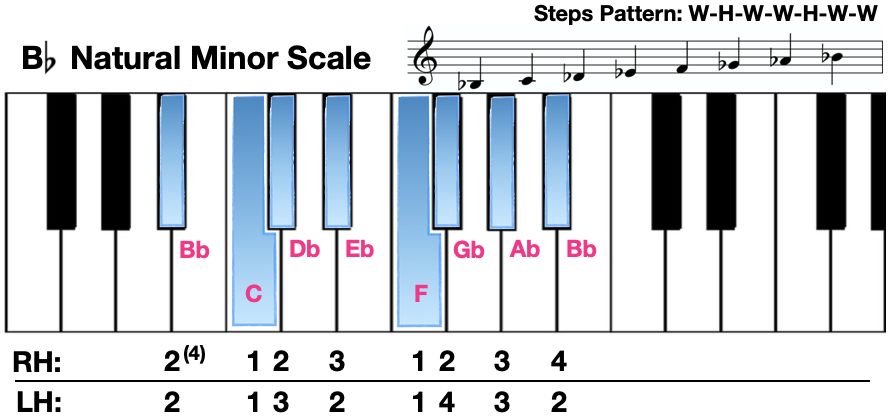

Notice the difference between the finger numbers between major scales that start on white notes and those that start on black notes. For the most part, major scales that start on white notes use the same fingering, while major scales that start on black notes generally have slightly different fingerings, and always start with a finger that is not the thumb.

Notice that the right hand in the next scale, F major, has a different fingering even though the scale starts on a white note. This is to avoid an awkward cross up to the Bb, which is not a comfortable move. In general, we try to avoid putting the thumb on black notes when playing piano scales.

Next come two additional enharmonically equivalent scales, F# major and Gb major. These scales mark the halfway point when climbing up the chromatic scale from C.

The remainder of the major scales have only one viable naming.

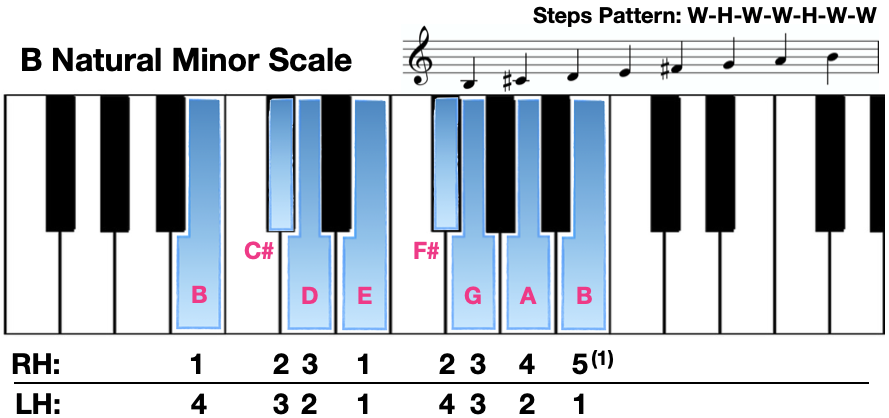

The last major scale at the top of the chromatic scale upwards from C is B major.

Now we'll move onto looking at the natural minor scales.

Natural Minor Scales

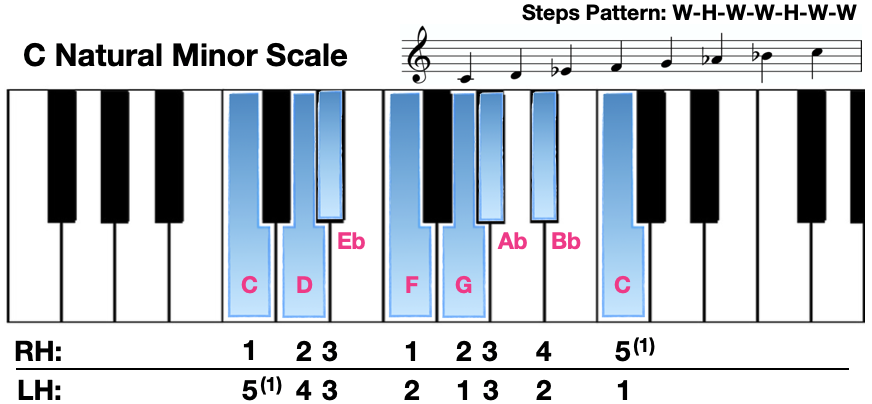

The most common kind of minor scale you’ll encounter at first is the natural minor scale, which takes the basic major scale, and “lowers” the 3rd, 6th, and 7th notes by a half step each. For example, to make a C major scale a C natural minor scale, we would lower the E to Eb, the A to Ab, and the B to Bb, giving us a scale that looks like this:

Natural minor scales have a much darker sound than major scales, and are often used to evoke more somber, serious, or sad emotions in music.

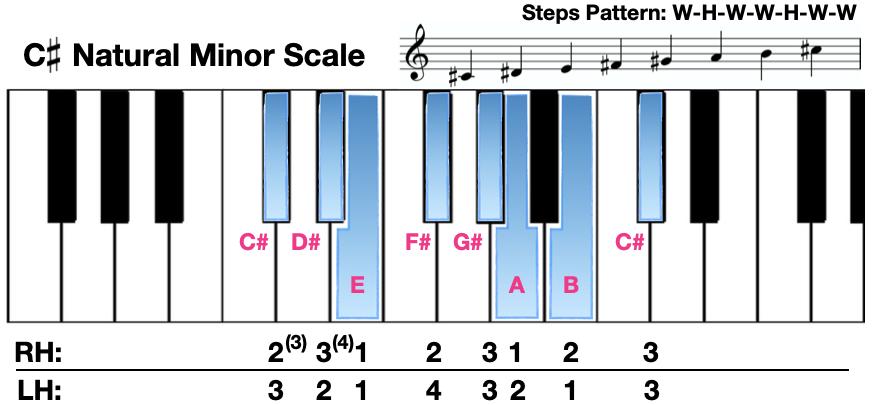

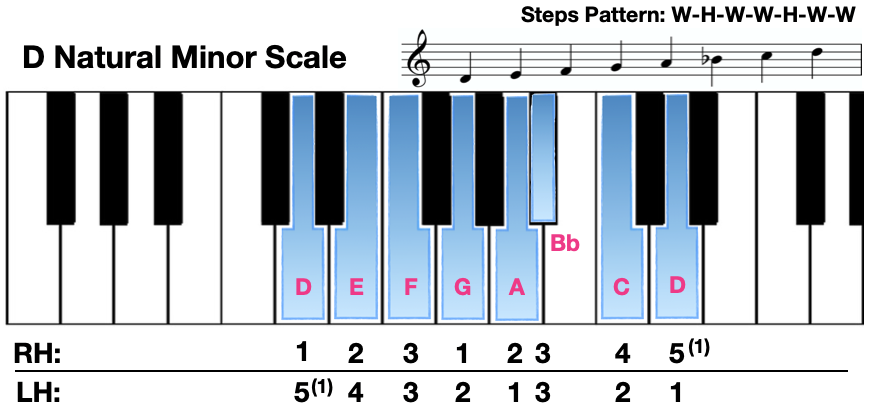

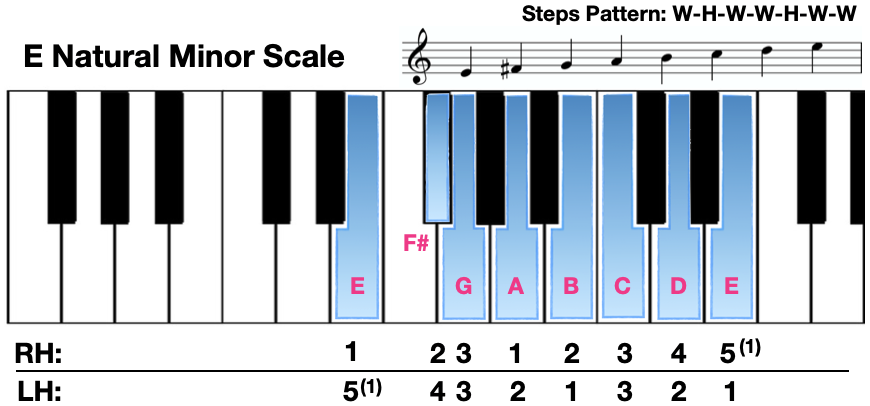

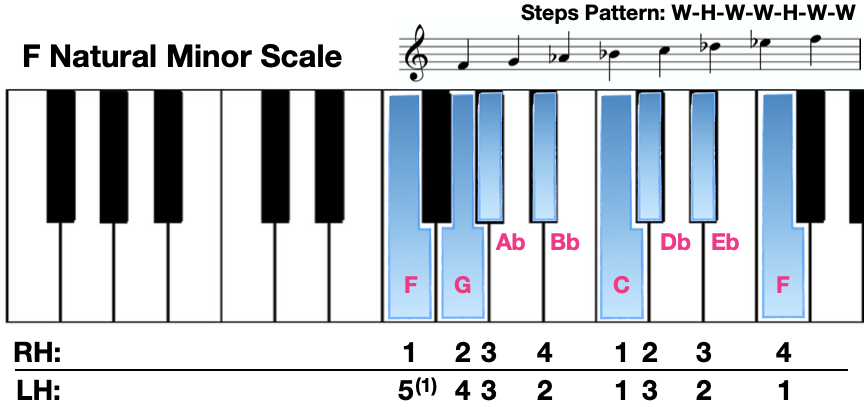

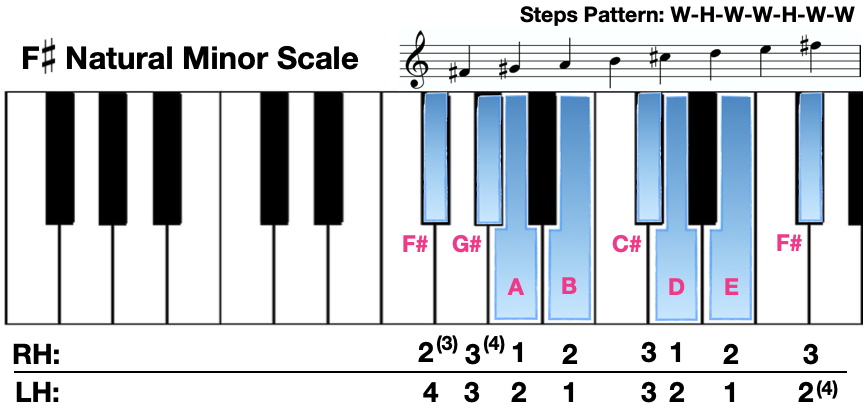

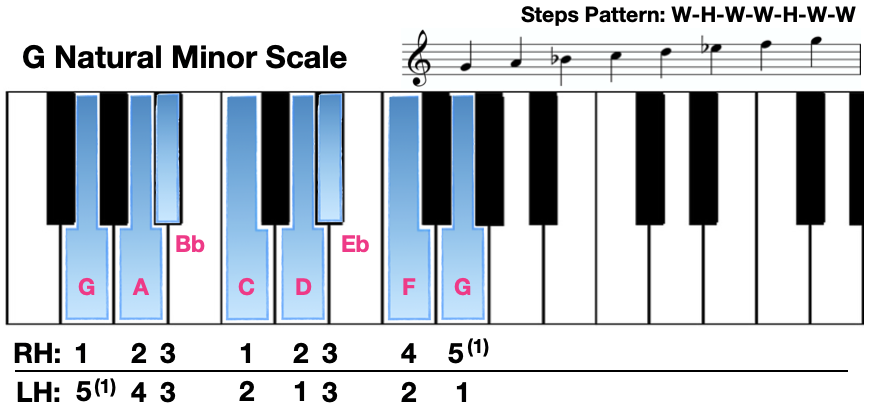

Here are the remaining natural minor scales.

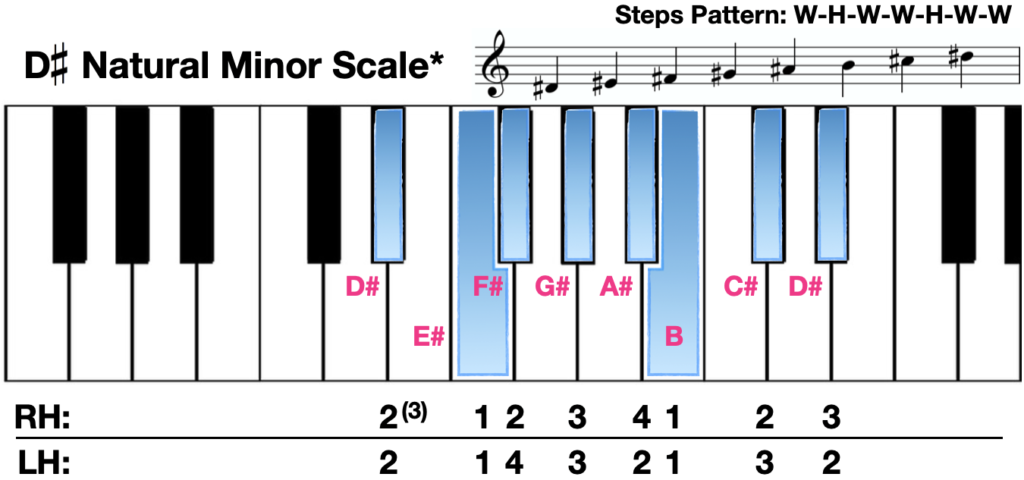

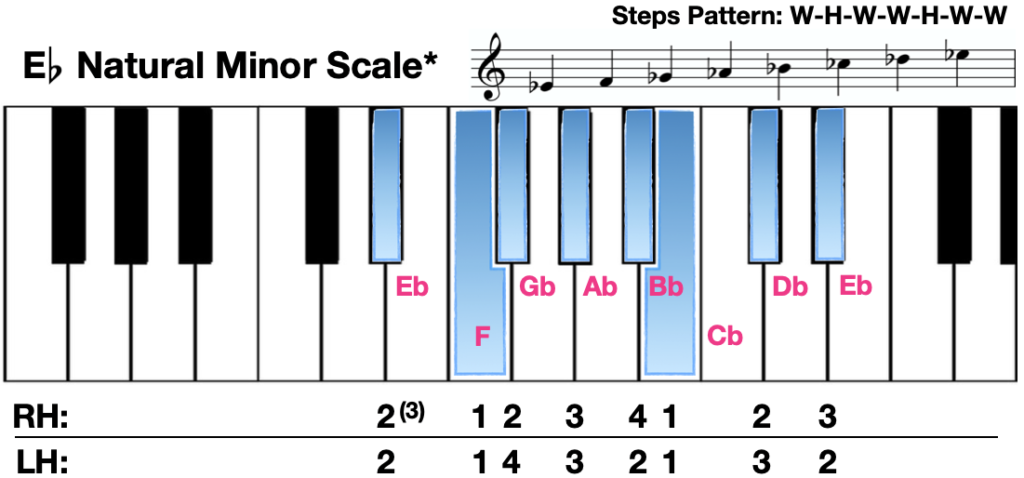

There are also enharmonically equivalent note spellings for natural minor scales, such as between D# natural minor and Eb natural minor.

Notice again how almost all of the fingering for the scales that start on white notes is the same pattern.

And also notice how the same alterations to that main fingering pattern are present in the natural minor versions of the major scales, such in the right hand in F natural minor.

Once again, F# marks the halfway point when moving up the chromatic scale from C. Here are the rest of the natural minor scales from F# to B.

Thanks for checking out this article from Liberty Park Music! If you liked what you saw here, you can find more in our blog at libertyparkmusic.com. We also have a YouTube page! And if you're really ready to take your music training to the next level you can subscribe to our site and gain access to a full spectrum of piano lessons.

Sign up for our free newsletter

Useful articles for musicians

About the Author: West Troiano

West has over 10 years of teaching experience in settings that vary from private studios to college classrooms. In addition to teaching through traditional forms of piano pedagogy, West frequently produces music and teaching materials that cater to the needs of his students. Check out West's course on Piano Etudes for both beginners and intermediate pianists.