Key signatures are some of the most commonly encountered elements of music notation. They are frequently used in western notated music, and even music beginners will probably come across them early in the music learning process.

But what exactly are key signatures? Despite their prevalence, key signatures can be strangely difficult to understand for beginners. In this article we’ll explain what key signatures are, where they’re found, and how to most easily think about what they do.

Where are Key Signatures, and What do they Mean?

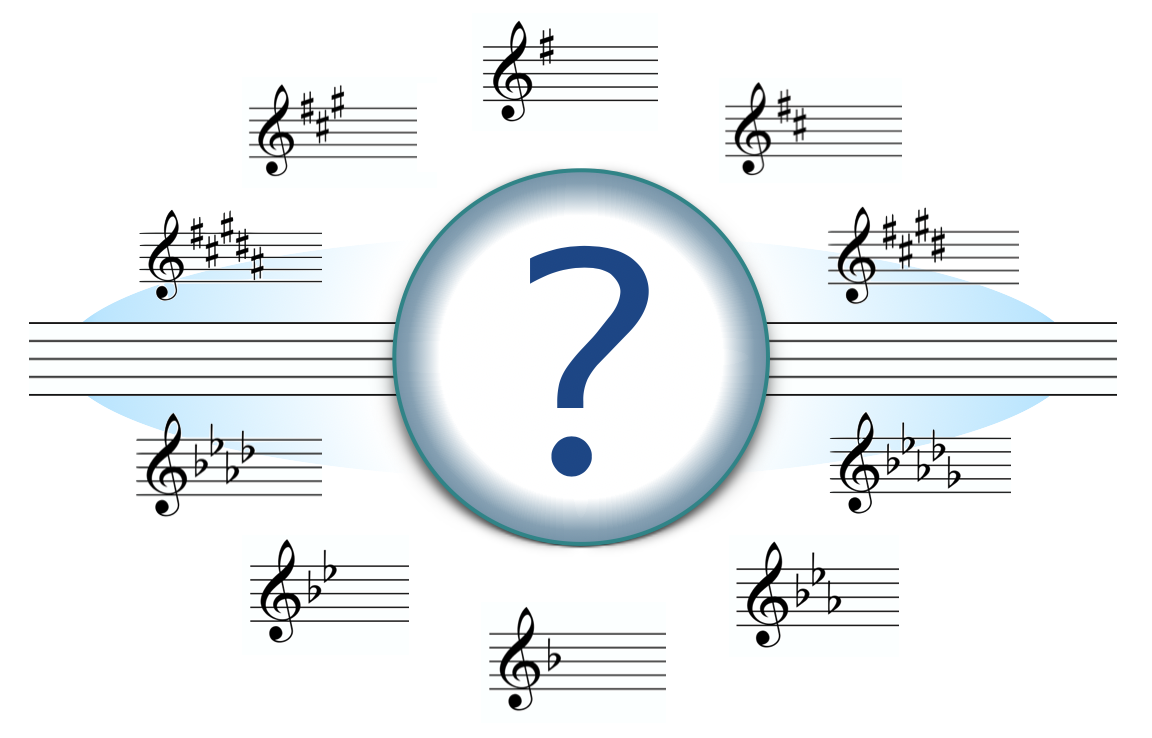

Key signatures are collections of accidentals that show up at the beginnings of pieces and staff systems. They appear after clefs, and before time signatures:

You can think of key signatures as indicating one of two very similar things: what “key” the piece is in, or what scale the piece is using. Of the two of these, thinking of the scale is much easier.

The definition of a “key” in music is a much bigger topic, and involves more familiarity with music theory. If you’re interested in learning more, check out the first article in our more comprehensive, “Discovering Keys” series here.

For now, it’s easier to think of key signatures as representations of the main scale being used for a piece. The sharps and flats (accidentals) seen in a key signature are the same ones used in the major and natural minor scales.

For example, if you see a key signature with a single sharp, like this:

Your scale options are the two scales that use one sharp: G major or E natural minor. The notes of either of these scales will be the primary ones you see in the piece (unless there is a key/scale change).

Similarly, if you see a key signature with one flat, like this:

Your scale options will be the two scales that use one flat: F major or D natural minor.

How to Identify the Scales of a Key Signature

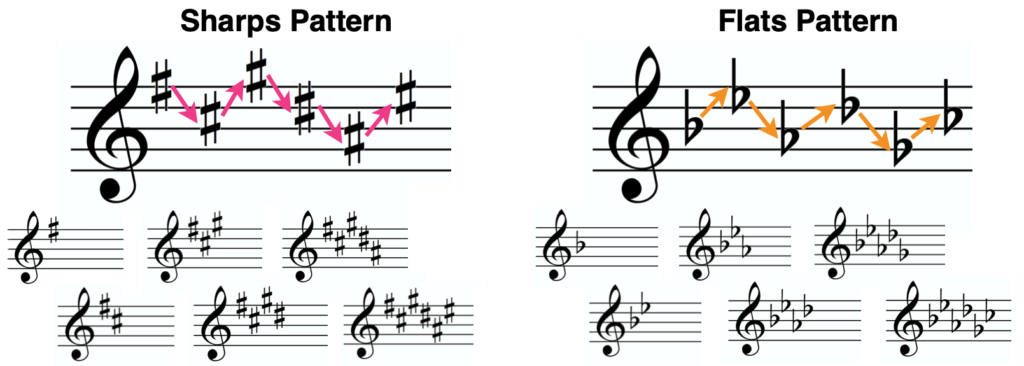

There are a number of ways to use the key signature to identify keys/scales. Accidentals are added to key signatures in a mostly zig-zag pattern, going down a 4th interval and up a 5th interval when starting from one sharp, and doing the opposite (up a 4th and down a 5th) when starting from a single flat. Accidentals should stay on or just outside the staff lines, so sometimes the pattern needs to be adjusted:

You can either memorize which scale uses a particular combination of sharps or flats by consistent identification, or you can use a mnemonic method to make things easier.

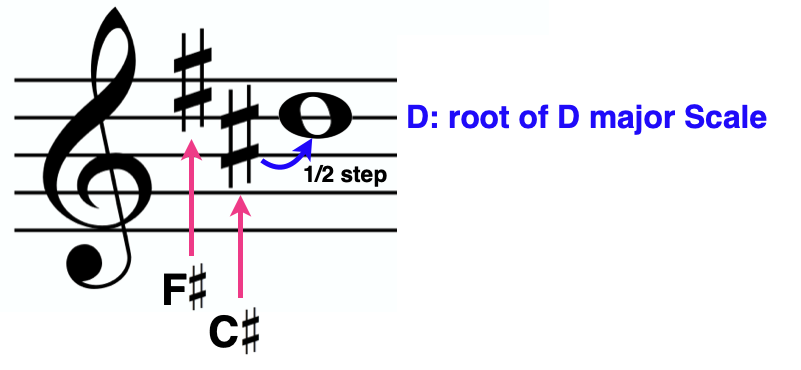

For sharps, one good method to help you figure out the scale of a key signature is to remember that the “root,” or bottom note, of the major scale is one line or space up from the last sharp that was added.

For example, the next sharp we add after F# is always C#, and the note one step up from C# is D:

D is the root of the D major scale, which uses two sharps.

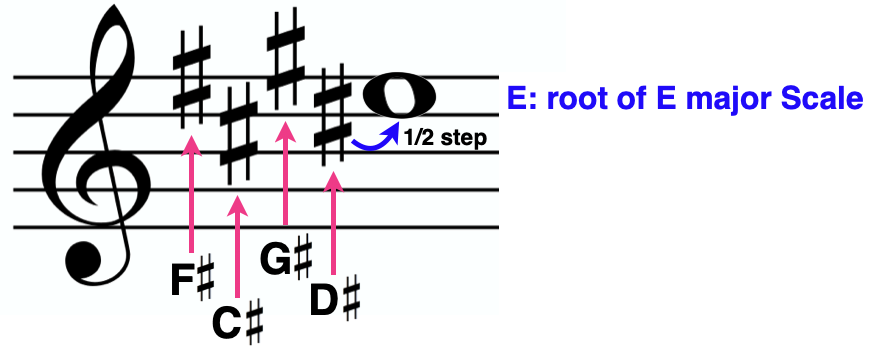

Let’s do the same thing with four sharps. The last sharp added in the zig-zig pattern when we have four sharps will always be D#. One step up from D# is E:

E is the root of the E major scale, which uses four sharps.

A slightly different method is available for key signatures using flats.

This time, the root of the major scale will always be the same as the accidental before the last one that was added. This only works once you have two or more flats, so you’ll still need to memorize the scales that use no flats (C major and A natural minor) and one flat (F major and D natural minor).

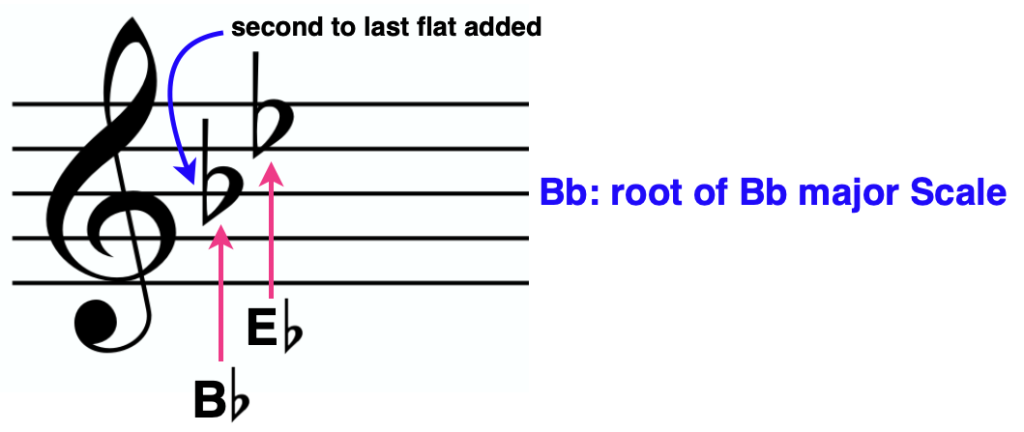

For example if we have two flats, the first will always be Bb, and the second will always be Eb. Bb is the accidental that came before the last accidental that was added, so the root of our major scale is Bb:

One more example; if we have six flats, the final flat that will have been added is Cb. The flat added before Cb is Gb, so the major scale that uses six flats is the Gb major scale:

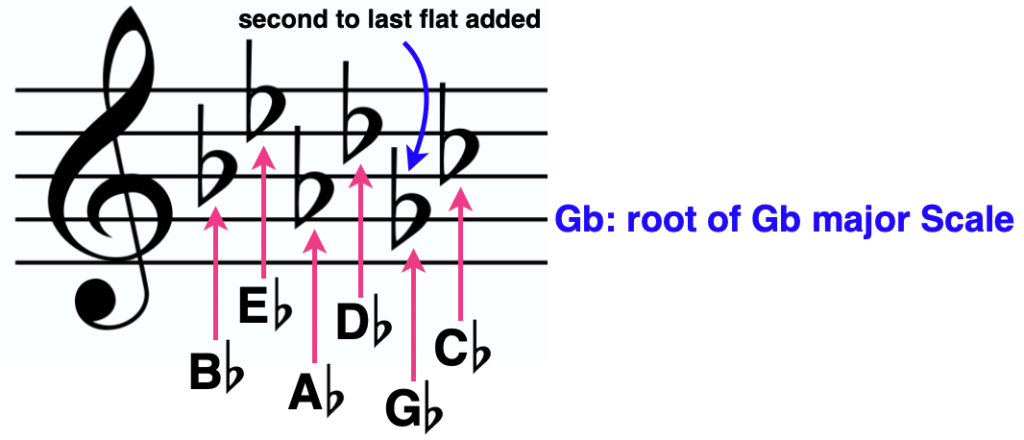

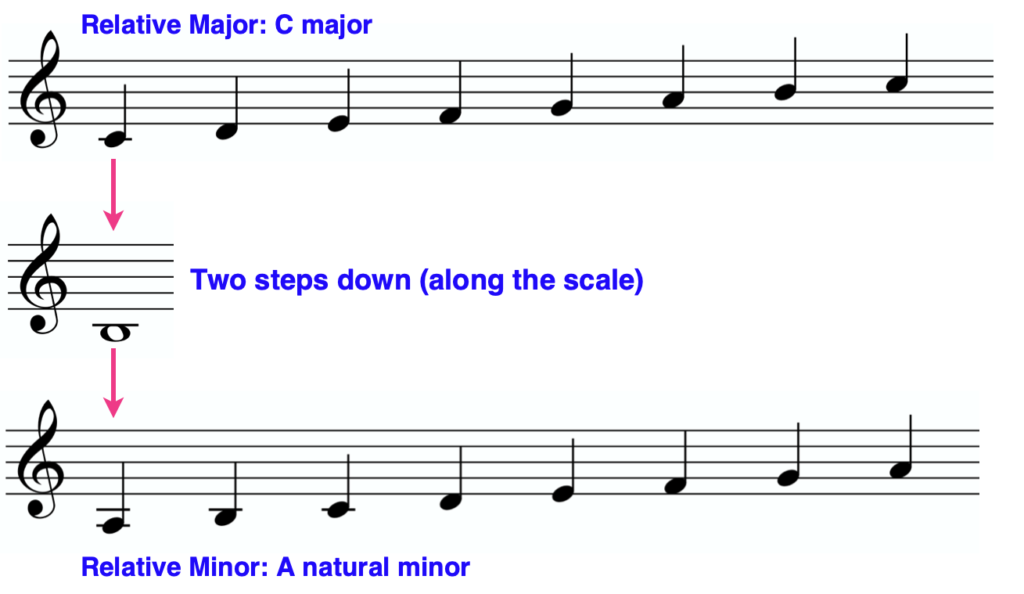

Finally, here are all of the key signatures paired with their major and natural minor scales:

Relative Major and Minor

Scales that share the same key signature are called “relatives” (e.g., D natural minor is the “relative minor” of F major, and visa versa). Knowing both scales that use the same accidentals can help greatly when you’re trying to identify which scale is being referred to by the key signature.

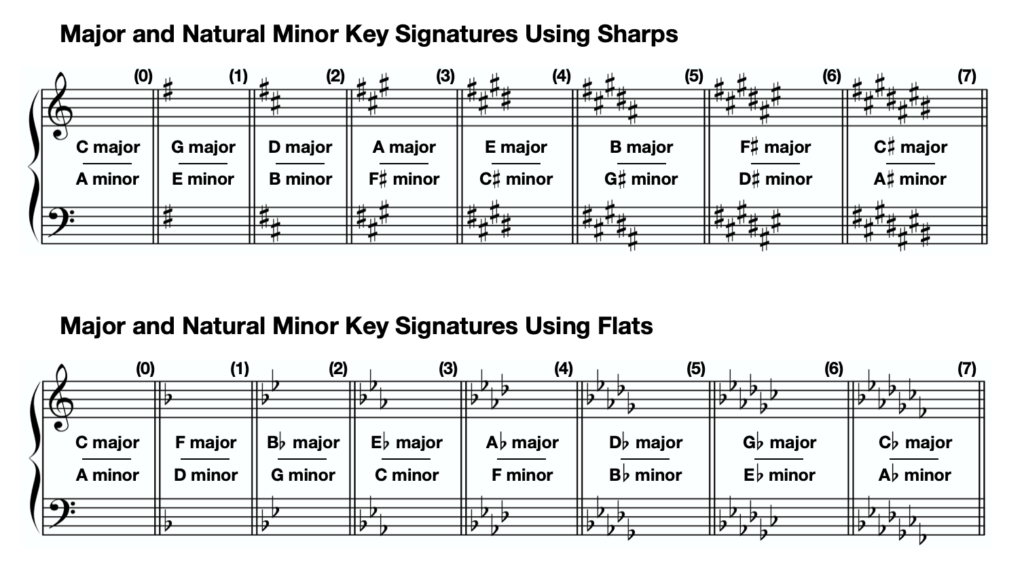

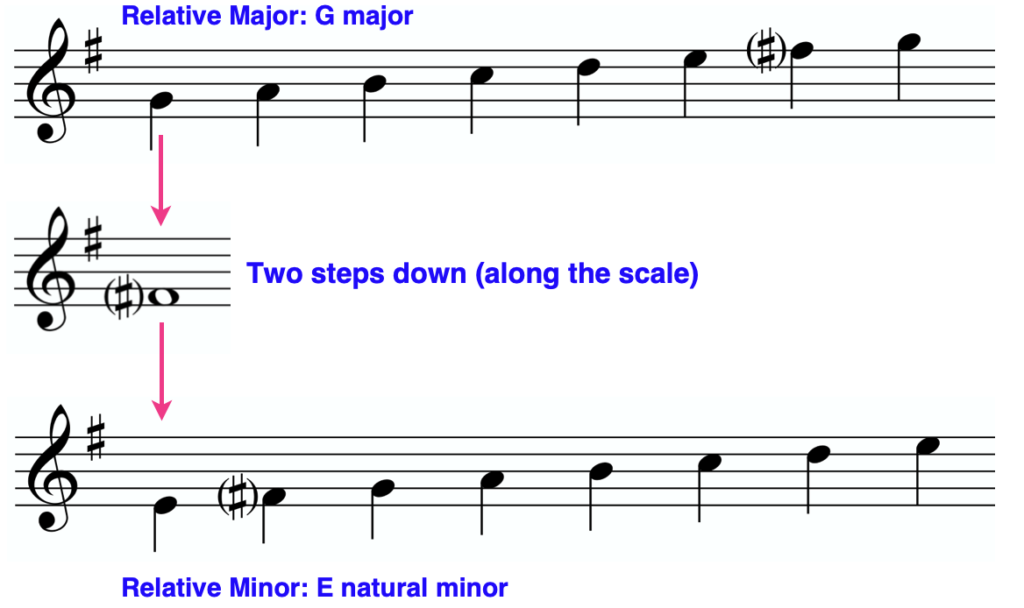

Relative major/minor scales are separated by two steps along the scale. For example, to find the relative minor of C major, you would start on a C, go back (or “down”) two steps along the C major scale, which lands you on A:

A natural minor is the relative minor of C major.

Let’s look at one more example. The E natural minor scale has all white notes except for one sharp, F#. Starting on E, if we go up the scale two steps, we land on G:

G major is the relative major of E natural minor.

In the example above you probably noticed the sharps in parentheses next to the notes; because we’re using a key signature, it’s customary to put any accidentals that are already in the key signature in parentheses. We call these “courtesy accidentals.”

Knowing whether a major or natural minor scale is being used for the piece can often be determined by looking at the first and last notes and harmonies; if you’re seeing notes that correspond to a F major harmony at the beginning and end, chances are that the scale indicated by the key signature is F major.

Using the Circle of 5ths to Identify Key Signatures

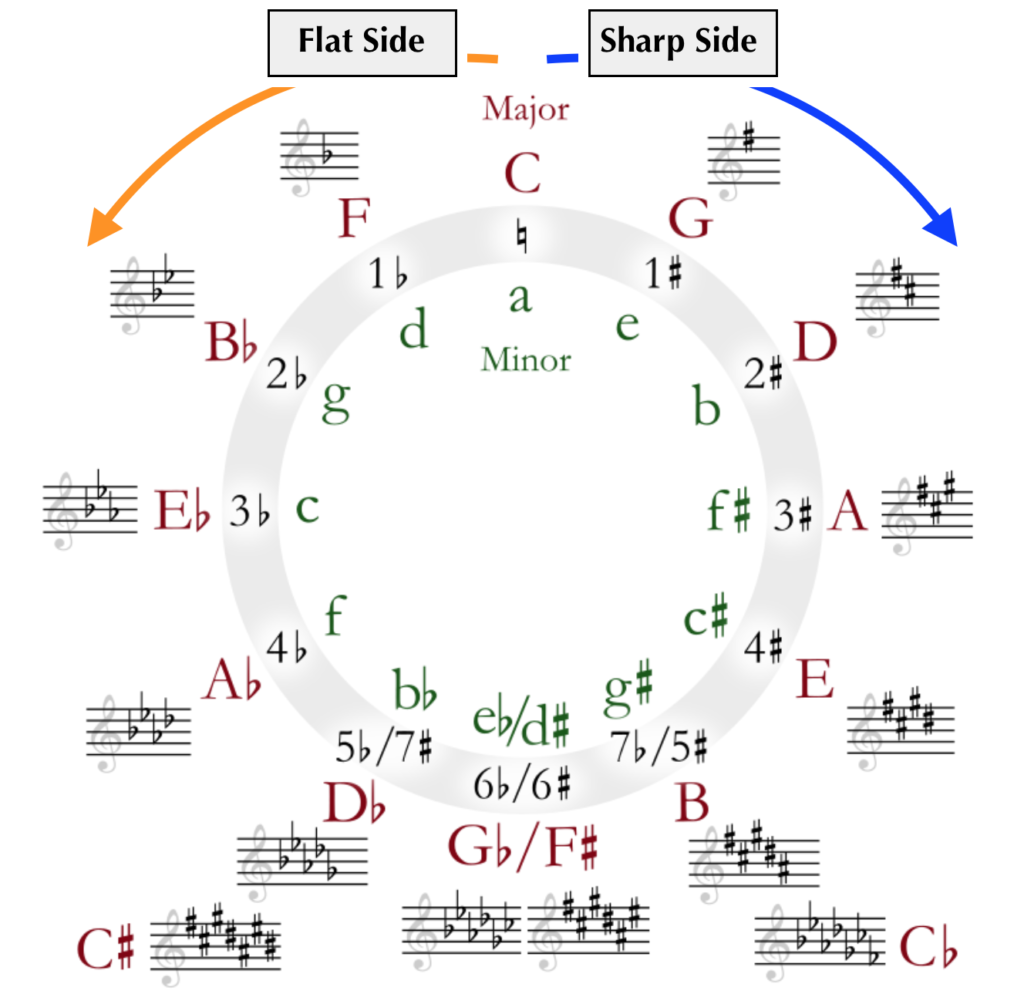

Until you’re familiar with the scales and which accidentals are associated with them, one of the easiest ways to determine which scales go with which key signatures is to use a Circle of 5ths diagram:

As you can see, the key signatures corresponding to the scales that use sharps are circling around to the right, while the scales that use flats are going to the left. The theory behind the Circle of 5ths is not important to know for key signature identification - you can use it very simply to tell you which scales go with which accidentals.

Notice that the names of the major scales are named on the outside of the circle, while the minor scales are named on the inside. Once again, you need to look at the first and last harmonies of the piece to help you identify whether the key/scale indicated by the key signature is major or minor. For most piano music, those harmonies will be either the “root” (1st) or “dominant” (5th) harmonies of the scale.

Why use Key Signatures?

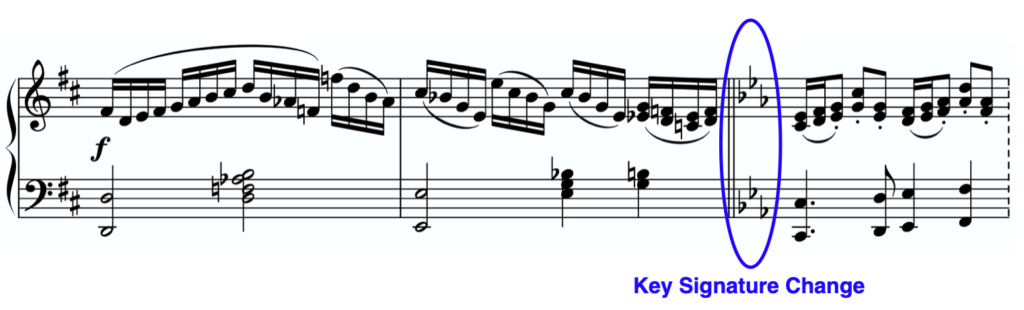

Part of the value of key signatures is that they allow the composer to avoid writing in the most common accidentals in the piece (those that are a part of the scale). The accidentals in a key signature are present on the notes they apply to for the entirety of the piece. For example, a piece with an F# in the key signature has all of its F’s sharped for its entire length, so the composer doesn’t need to write them in every time.

Thanks for checking out this article on key signatures from Liberty Park Music. For more articles and music lessons, be sure to visit us on YouTube, and at libertyparkmusic.com!

Sign up for our free newsletter

Useful articles for musicians

About the Author: West Troiano

West has over 10 years of teaching experience in settings that vary from private studios to college classrooms. In addition to teaching through traditional forms of piano pedagogy, West frequently produces music and teaching materials that cater to the needs of his students. Check out West's course on Piano Etudes for both beginners and intermediate pianists.

Very informative…

Thank You,

Michael