The name “Beethoven” is one of the most recognizable in all of classical music. Ask anyone to name a few classical composers, and among the short list you’re likely to get, one of names will almost certainly be Ludwig van Beethoven. Beethoven’s music continues to receive regular airtime through both performances and media spots, and a number of the most popular melodies from the classical world come from his compositions.

In this article we’ll take an introductory look into the life and music of Ludwig van Beethoven.

Life and Times

Early Life

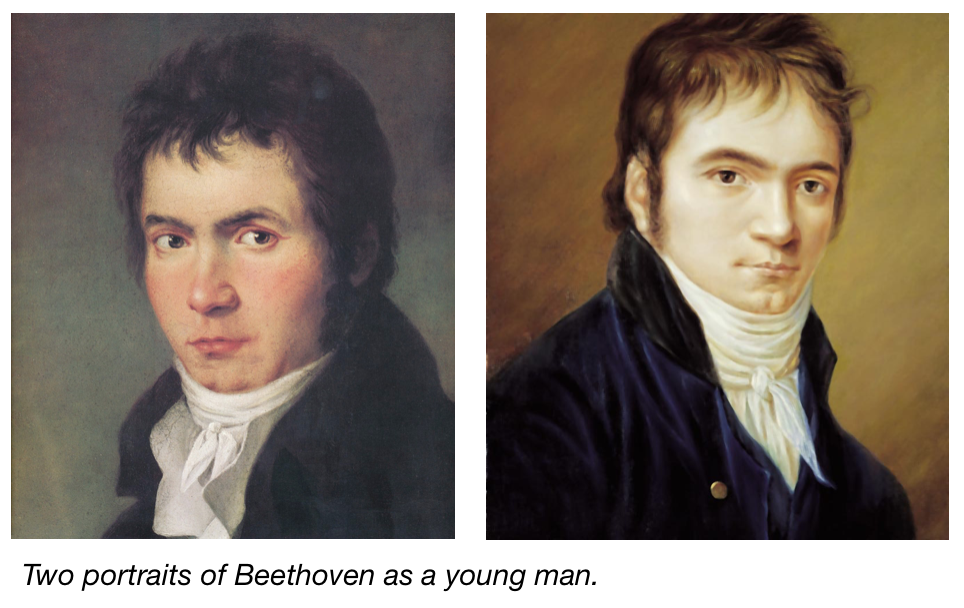

Ludwig van Beethoven was born in 1770 in the German city of Bonn, which at the time was part of the large, central European political conglomerate known as the Holy Roman Empire.

Beethoven’s grandfather (also named Ludwig) was a notable singer and Kapellmeister (musical director) in Bonn, working for the aristocratic court of Clemens August, Archbishop-Elector of Cologne. Beethoven’s father, Johann, failed to recreate the elder Ludwig’s successes, and much of his son’s early life was punctuated by his overbearing presence and alcoholism.

Beethoven’s profound musical talents were evident from an early age, and Johann van Beethoven was quick to take advantage of the financial benefits he could reap by exploiting that talent. Well aware of the successes of Leopold Mozart with his own prodigious son, Wolfgang Amadeus, Johann subjected the young Beethoven to a tyrannical practice regime, and the involvement of additional teachers only added to the workload. In addition to keyboard training (at which he excelled), Beethoven was also trained to play string instruments such as the violin, and was also tutored in the art of composition.

Like many musicians seeking to make a name for themselves during this time, Beethoven would ultimately relocate to the Austrian capital of Vienna, which was the center of the European musical world at the end of the 18th century. The residence of famed figures like Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart further functioned to centralize the city as the core of Western art music.

Beethoven in Vienna

Beethoven’s first trip to Vienna occurred in 1786. While it is generally acknowledged that he intended to study with the legendary Mozart, it is uncertain that they ever met, and Beethoven’s visit to the city was cut short by his mother’s failing health and his father’s increasing incompetence, the combination of which necessitated his return to Bonn. Beethoven’s mother died shortly after his return, and Johann’s increasingly alcohol-induced ineptitude left the teenaged Beethoven to look after both the family’s financial straits (which he partially accomplished by assuming control of part of his father’s income), as well as his two younger brothers, Johann and Kaspar, both of whom would later come to aid Beethoven with the business side of his musical affairs. A second trip to Vienna occurred in 1792, when Beethoven ultimately studied for a year with Haydn. While the details of Beethoven and Haydn’s relationship as student and teacher remain largely unknown, the evidence of Haydn’s (and Mozart’s) musical influence on Beethoven is clear in his early compositions.

Beethoven’s initial fame in Vienna stemmed more from his skills as a virtuoso pianist than as a composer, with his prowess as an improvisor being of particular note. Beethoven’s official output as a composer began with the 1795 release of his Opus 1, a set of three piano trios, which was written for one of his most prominent patrons, Prince Karl Lichnowsky. Throughout his life Beethoven’s patrons would remain his most significant source of support and income, which was not uncommon for artists of particular skill in Vienna and other major cities at the time. Beethoven also stepped into the ring of teaching, and, in addition to the obligatory demographic of aristocratic daughters and well-to-do amateurs, aided in the development of several notable composers.

Hearing Loss and the Heiligenstadt Testament

In 1798, after an event that has been variously described as a pronounced illness or physical ailment brought on by a fit of stress, Beethoven first realized that he was losing his hearing. While it would be more than a decade before the effects were profound enough to incapacitate his performance career, the advent of this malady was alarming enough to send him into a great depression, and in 1802 (on the orders of a physician), he retired for the summer months to the idyllic town of Heiligenstadt, just north of Vienna. There, he wrote a tragic missive of despair and determination in which he revealed his struggle with his encroaching deafness, his thoughts of suicide as a possible solution to this struggle, and his conclusion that he would instead persevere for the sake of his art and its benefit to the world. This document, written as a will to Beethoven’s brothers, is now known as the Heiligenstadt Testament, and in its wake Beethoven entered into the fertile phase of productivity and creative innovation known as his “middle period.”

In 1798, after an event that has been variously described as a pronounced illness or physical ailment brought on by a fit of stress, Beethoven first realized that he was losing his hearing. While it would be more than a decade before the effects were profound enough to incapacitate his performance career, the advent of this malady was alarming enough to send him into a great depression, and in 1802 (on the orders of a physician), he retired for the summer months to the idyllic town of Heiligenstadt, just north of Vienna. There, he wrote a tragic missive of despair and determination in which he revealed his struggle with his encroaching deafness, his thoughts of suicide as a possible solution to this struggle, and his conclusion that he would instead persevere for the sake of his art and its benefit to the world. This document, written as a will to Beethoven’s brothers, is now known as the Heiligenstadt Testament, and in its wake Beethoven entered into the fertile phase of productivity and creative innovation known as his “middle period.”

Middle and Later Years

After facing the reality of his approaching deafness in 1802, Beethoven committed himself wholeheartedly to his work. In addition to the increasing liberties Beethoven began to take with musical expression and form, many of his works from this time assumed a grand, determined quality that is often interpreted as “heroic” in character. For this reason, Beethoven’s middle period is occasionally referred to as his “Heroic” period.

After facing the reality of his approaching deafness in 1802, Beethoven committed himself wholeheartedly to his work. In addition to the increasing liberties Beethoven began to take with musical expression and form, many of his works from this time assumed a grand, determined quality that is often interpreted as “heroic” in character. For this reason, Beethoven’s middle period is occasionally referred to as his “Heroic” period.

By 1810, Beethoven was approaching the peak of his professional career, accruing both artistic and financial success through performances, sales of published works, and on the good graces of his patrons.

But while Beethoven’s professional success waxed, his personal well-being fell into greater disrepair, and the effects of his deafness soon became unmanageable. By 1811, Beethoven was almost completely deaf. He ceased performing in public, and began to avoid social engagements. During the last 9 years of his life he relied on notebooks to communicate with confidants and associates, reading the written questions or statements and responding either verbally or in writing. While many of these “conversation books” were lost in the aftermath of Beethoven’s death (possibly destroyed at the hand of one of Beethoven’s closest devotees, Anton Schindler), the books that do remain offer significant insight into the day-to-day interactions of the great composer.

Beethoven faced trials beyond those related to his hearing loss as well during this period. In 1814, Beethoven’s brother Kaspar died after a lengthy fight with tuberculosis, leaving his son Carl in the joint custody of Beethoven and the boy’s mother, who Beethoven determined was too unsound of character to adequately provide for Carl’s upbringing. Thus ensued a prolonged custody battle, after which Beethoven assumed responsibility for Carl as a dependent. This relationship was far from harmonious, and Carl unsuccessfully attempted suicide 1826. While the two men would eventually come into good terms before the final year of Beethoven’s life, the entire experience was no doubt stressful for the aging composer. In addition to all of this, Beethoven struggled with his own illnesses throughout this time, and his output dropped as a result.

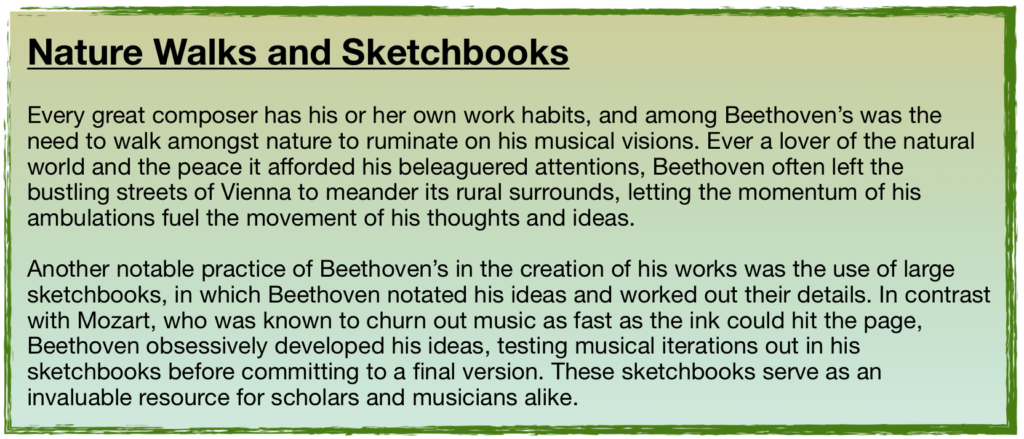

In early 1818 Beethoven had sufficiently recovered from his emotional and physical afflictions to resume a more regular pace of composition. Beethoven’s designs had shifted into incorporating the older, more focussed contrapuntal styles of composers such as J.S. Bach and Handel into his own style, and the results yielded a unique and powerful blend of Beethovenian grandiosity and Baroque complexity. This period is known as his late period, and the compositions from this time include piano works such as the final five sonatas and the remarkable Diabelli Variations, the final string quartets (including the aforementioned Große Fuge), the Ninth Symphony, and the great choral Mass setting, the Missa solemnis (solemn mass). Much of this music was challenging for audiences and musicians of the time to comprehend, and, while many critics touted Beethoven as the greatest musical genius of the generation, others were less impressed with his insistent iconoclasm.

Despite this, Beethoven still achieved some success through performances of his work, and his premiers were generally well attended. By this point, Beethoven had relegated himself to watching from the sidelines, and by the premier of his Symphony No. 9 in 1824 Beethoven had not been onstage for 12 years. The announcement that Beethoven would attend the premier concert, which took place at Vienna’s Theater am Kärntertor on May 7th, 1824, attracted droves of fans and fellow musicians. It is from this engagement that we have one of the most poignant anecdotes of Beethoven’s life. As the story is recalled, Beethoven was insistent on conducting the premier alongside the venue’s musical director, Michael Umlauf, but his deafness guaranteed major logistical issues, so alternative plans were made. Beethoven would stand aside Umlauf to conduct, but the orchestra was directed to focus solely on Umlauf’s cues. This proved a wise course of action: in addition to his wild physical articulations and gestures, Beethoven also ended up several measures off at the piece’s end, and was still flailing his arms as the music stopped and the ovations began. Unable to hear the thunderous applause, Beethoven had to be turned around on the stand to experience the acclaim of his audience.

Beethoven’s final years were mostly spent battling the effects of his failing health, and in the late months of 1826 he suffered an acute illness from which he would not recover. Friends and relatives gathered in preparation for his passing, and on March 26, 1827, Ludwig van Beethoven died. Accounts of this event agree that a thunderstorm raged outside during Beethoven’s death, and this point of interest has provided a fertile backdrop for a number of romanticized renderings of Beethoven’s final moments.

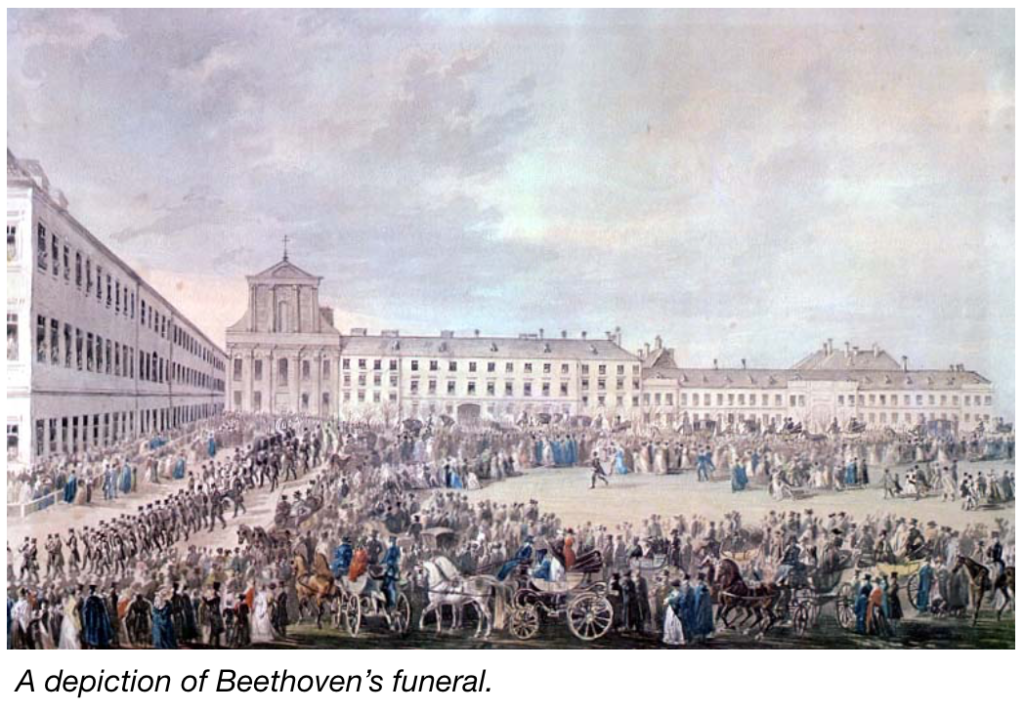

Beethoven’s funeral in Vienna was attended by an estimated 20,000 people, and among his torchbearers were several estimable composers, including Franz Schubert, and Beethoven’s most famed student, Carl Czerny. While this would hardly be the end of the city’s musical legacy, Beethoven’s passing coincided with the passing of musical eras: Classical period had run its course, it was time for the Romantics to take the reins.

The Music of Beethoven

Beethoven wrote in a variety of different genres, and produced works in most of the accepted genres of the time. He wrote songs, piano trios, choral music, marching band music, masses, and a single opera, Fidelio, which found significant success during Beethoven’s time but has largely fallen into secondary recognition today. His piano concertos are considered essential additions to the format, setting the standard for similar entrees to the genre in the decades to come. Despite all of that, Beethoven is most commonly remembered for his symphonic works, string quartets, and works for solo piano.

Beethoven often pushed the boundaries of dramatic expressivity, and tested the limits of the traditional structures of Classical form. Indeed, some of the most identifiable features in Beethoven’s music are its dynamic extremities and extended development sections. Raging fortissimos and delicate pianissimos are written adjacent to one another, defying the traditional Classical expectation for expressive evenness. In the same vein, while Beethoven rarely broke the Classical “rules” of form and function, he often hyperextended them beyond anything previously seen or anticipated.

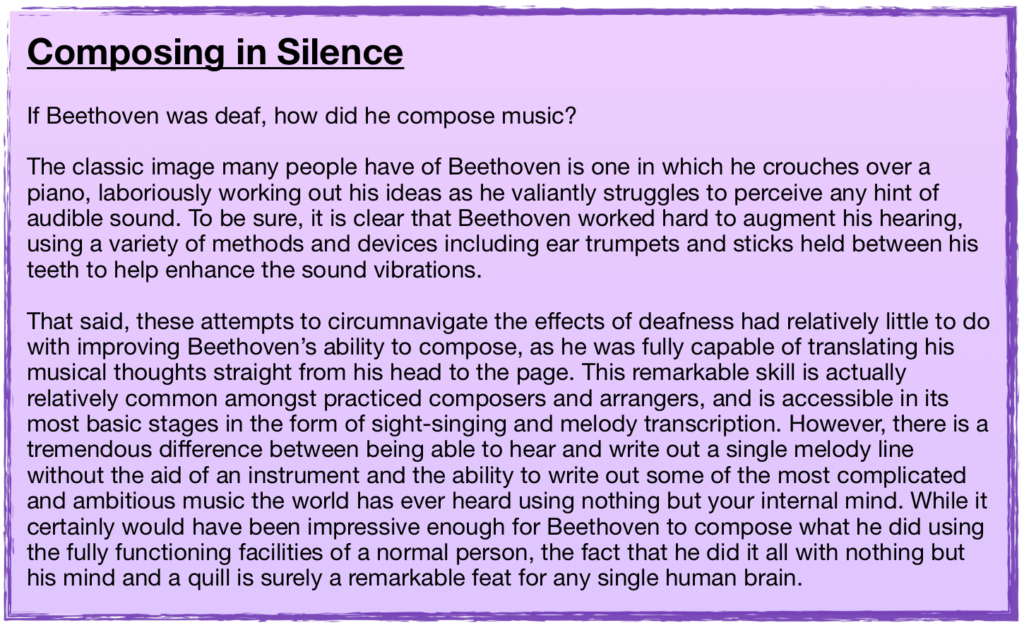

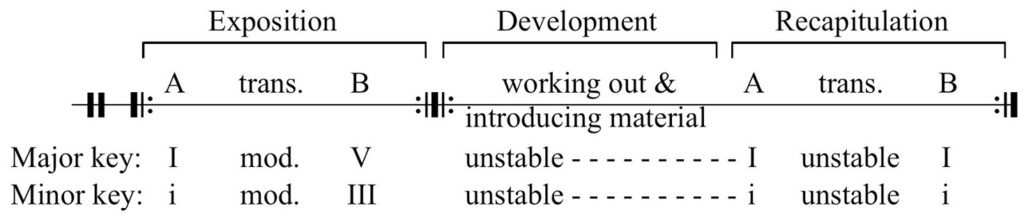

Take, for example, the quintessential form of many first movements from the Classical period, sonata allegro form, which can be seen in the diagram below:

The development section in sonata allegro form is typically where composers expand the core thematic material with varied iterations, modulations, and sequential restatements. Whereas the development sections of Mozart and Haydn are relatively short affairs, Beethoven’s development sections become vast, adventurous musical expeditions that seem bent on exhausting every conceivable option for tension and resolution. To provide a quick example: the first movement of Mozart’s famous late Symphony No. 40 in G Minor (K. 550) has a development section that is 62 measures long, while the development section of the first movement of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony weighs in at a whopping 128 measures long. This exploratory insistence is a key characteristic in Beethoven’s music, and it became a prototype for the evolutionary ideals that governed much of classical music for over a century after his death.

Symphonic Works

Beethoven’s symphonies are some of the most recognized works in the Western classical canon, and nearly all of them were composed during Beethoven’s middle period, (1802–c1814). In contrast with the likes of Haydn and Mozart, who each wrote large numbers of symphonies, Beethoven only composed nine. Beethoven’s nine symphonies are often revered for their creative depth, their technical mastery, and their deviation from key aspects of the traditional Classical paradigms.

Beethoven’s two early symphonies, No. 1 in C Major and No. 2 in D major (published in 1800 and 1803, respectively), clearly resemble the symphonies of Haydn and Mozart in Classical aesthetic and form, but also demonstrate Beethoven’s penchant for grander gestures and increased dynamic extremes. While typically considered preliminary in the greater scheme of Beethoven’s output, they are nonetheless important precursors to the symphonies of the middle period.

Beethoven’s realization of his impending deafness in 1803 sparked the most productive decade of his life, and he soon presented the world with the ambitious work that would jostle standards and eardrums alike. Performed for the first time publicly in 1805, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 in Eb Major (dubbed “Eroica,” or “heroic”) was hailed as brilliant by some, and nonsensical by others. For starters, the first movement (which can clock in at almost half an hour) is as long as an entire Mozart or Haydn symphony, and much of its thematic material is developed seamlessly over the course of its hybrid form. This work is also often considered to be the first true expression of the musical identity for which Beethoven would come to be known.

Listening: Symphony No. 3, Op. 55, “Eroica”

Perhaps the most famous of Beethoven’s symphonies is his Symphony No. 5 in C Minor, Op. 67. This symphony’s tempestuous first movement continues to be one of the most popular works from Beethoven’s oeuvre, and also possesses arguably the most recognizable motif in all of Western classical music. The development of the da-da-da-duuum motif is often touted as an exemplification of Beethoven’s tendency to whittle melodic, rhythmic, or harmonic ideas down to a small, core structure, which is then represented in various iterations throughout the composition. While this sort of fragmentary development of musical material was hardly uncommon at the time, the extremity of Beethoven’s deconstructive process is unique. Listen to how the opening motif is developed throughout the opening movement of the 5th Symphony:

Listening: Symphony No. 5, Op 67

Another symphony of note is Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125, which, in addition to its vast size and expressive extremes, incorporates a choral element into its final movement, and features another of Beethoven’s most recognized themes, the musical setting of Friedrich Schiller’s poem, “Ode to Joy.” In addition to acting as a precursor to the Romantic period in terms of its dramatic aesthetic, this symphony is notable for its quasi-programmatic characteristics. Recall that a programmatic piece employs extra-musical material in the construction of its creative narrative. This extra-musical material can be a story, an event, or a characterization. In the Ninth Symphony, this is most evident at the beginning of the fourth movement, when a progression of restatements of the thematic material from previous movements are apparently tossed aside one after another by a stern and powerful cello line, to be replaced by the unassuming and peaceful melody of the “Ode to Joy” setting. This cello part has occasionally been interpreted as being the voice of Beethoven dismissing the conceits and extravagances courted by humanity in favor of a purer, simpler truth.

Listening: Symphony No. 9, Op. 125, “Choral”

Piano Sonatas

The 19th-century pianist and composer Hans von Bülow, who was the first to perform all of Beethoven’s sonatas from memory, famously called Johann Sebastian Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier the “Old Testament” of keyboard music, and Beethoven’s complete collection of piano sonatas the “New Testament.” Alongside the works of other major names like Chopin, Bach, Debussy, and Mozart, Beethoven’s sonatas are the most well-known and frequently-played keyboard pieces in classical literature.

Of the 32 sonatas Beethoven wrote over the course of his life, nearly 20 were written before the Heiligenstadt Testament of 1802. While many of these early sonatas are clearly marked by the influence of Haydn and Mozart, some notable exceptions stand out as quintessentially Beethoven. Sonata No. 8, commonly referred to as the “Pathétique” sonata demonstrates Beethoven’s ability to transform the opera-inspired sense of drama found throughout Mozart’s music into powerful and technical gestures of instrumental acumen. Its intensely somber, grave entrance is unlike any found in the sonatas of Haydn or Mozart:

Listening: Sonata No. 8 in C Minor, Op. 13, “Pathetique”

Composed slightly later and just before Beethoven’s move into his middle period are the two sonatas of Op. 27, entitled “Sonata quasi una fantasia” (“Sonata in the manner of a fantasy”) by Beethoven on his manuscript. The second of these sonatas, dubbed “Moonlight” by a critic some years after Beethoven’s death, is one of the most popular pieces in piano literature, and its somber, funereal first movement has been used in countless pieces of modern day media. You’re probably familiar with this ubiquitous first movement, but did you know that the final movement of this sonata is a fierce exhibition of pianistic speed and drama? Give it a listen!

Listening: Sonata No. 14 in C# Minor, Op. 27, “Moonlight”

The sonatas of Beethoven’s middle period exhibit similar changes to those in his symphonic writing. Development sections became longer, unusual key changes became more common, and technical gestures resulting in unique and evocative piano soundscapes continued to broaden the scope of what could be done with the instrument.

Several especially famous sonatas emerged from this time frame, and they all exhibit one or another of the features mentioned above. Sonata No. 21 in C Major, called the “Waldstein” after its dedication to Beethoven’s friend and frequent patron, Count Ferdinand Ernst Gabriel von Waldstein, vacillates between tight formations of repeated chords and sweeping arpeggios, and includes a unique modulation to the key of E Major for its second theme. (An analysis for this can be found in the final article of our What are Keys? article series, found here.)

Meanwhile, Beethoven’s predilection for the contrast between aggressive displays of virtuosic brilliance and gentle interludes of subtle harmonic intensity was being developed in works such as the challenging Sonata No. 23 in F Minor, popularly known as the “Appassionata.”

The piano sonatas of Beethoven’s late period pushed the boundaries of the musical conventions of his time. Starting with Sonata No. 28 in 1816 and ending with Sonata No. 32 in C Minor in 1822 (just five years short of Beethoven’s death) these sonatas remain some of the most engrossing and demanding works in classical literature. One in particular, Sonata No. 29 in B-flat Major, called the “Hammerklavier,” despite the diversity of its compositional elements (which include everything from flowing passages of airy arpeggios, to slammed octave melodies, to detailed fugal passages) is known almost exclusively for its tremendous difficulty. Much like the later works of Bach, Beethoven’s late piano sonatas reach for the zenith of the stylistic possibilities of their time and foreshadow developments that occurred long after their final notes were penned.

Listening: Sonata No. 29 in B-flat Major, Op. 106, “Hammerklavier”

String Quartets

Another genre in which Beethoven composed a remarkable body of work was the string quartet. The format of the string quartet as it was inherited by Beethoven was developed almost exclusively by his one-time teacher, Joseph Haydn, and, as with his early piano sonatas, Beethoven’s early string quartets (Op. 18) possess features similar to those of Haydn or Mozart. Beethoven’s true contributions to the genre began in his middle period, with the three Op. 59 quartets known as the “Razumovsky” quartets, after the man who commissioned them, Count Andrey Razumovsky.

The string quartet format affords composers a vast palette of polyphonic and homophonic combinations to spread beneath the four instruments. String instruments such as the violin, viola, and cello, are capable of powerful expressivity, and offer a diverse array of effects and articulations. For Beethoven, these options provided a veritable playground for musical interaction, and many of Beethoven’s characteristic compositional preferences for expansiveness and expressive manipulation can be found throughout his string quartets. For example, take note of the great length of the opening movement of the first of the three “Razumovsky” quartets, and listen to how the opening cello and violin lines of the introduction seem to float over the gently pulsing background, never quite committing to an arrival at the home key until a full 19 measures into the piece.

Listening: String Quartet No. 7 in F Major, Op. 59, No. 1, “Razumovsky”

The string quartets of Beethoven’s late period were composed in the final five years of his life, and are often highly regarded for their expressive creativity and structural depth. These works demonstrate a broad spectrum of technical and emotional diversity, ranging from ferocious passages of contrapuntal drama such as those featured in the fantastically difficult and immense Große Fuge, Op. 133, to achingly beautiful adagios such as the opening movement of quartet No. 14 in C Minor, Op. 131. Franz Schubert requested that Op. 131 be the final work that he heard before his death.

Listening: String Quartet No. 14 in C# Minor, Op. 131

Conclusion - Why Beethoven?

Beethoven’s music holds a place of importance in the trajectory of Western music. While it might not be apparent to the casual listener, many of the musical developments pioneered by Beethoven can be traced through time to their effects on music in the modern day. We hear the remnants of his harmonic and expressive innovations in music for film and TV shows, and students of composition still turn to Beethoven’s deconstructive methods of thematic development to better understand the possibilities of their musical ideas. Beethoven’s musical identity has consistently withstood the attrition of time, and knows fewer boundaries of geography and society than that of perhaps any other composer. And while not everybody has a preference for Beethoven’s musical aesthetic or the typically laudatory character of his heritage, few can argue the influence of his music and his name in the history of classical music.

So go check out some Beethoven! And don’t forget to look out for further entries to Liberty Park Music’s Composer Bios series.