The Romantic Period, spanning from around 1820 to 1910, contains some of the most beloved music from the classical music tradition. A lot of music from this time period is probably already familiar to you, due to its frequent use in television shows, commercials, movies, and video games! The highly expressive nature of Romantic music tends to resonate with the emotional sensibilities of the modern world, and it is this trait perhaps above all others that has contributed to its lasting appeal.

What is Romanticism?

Musical Romanticism was influenced by the Romantic movement in art and literature that began in the late 1700s. The Romantics reacted to the growing rationalism of the 18th century, choosing instead to emphasize the importance of the individual, and of emotional experience. Of the many emotional experiences highlighted through Romanticism, the most common is longing--longing for a love that is unattainable, longing for a homeland that cannot be returned to, longing for the return to a “simpler” life from the past (or just a better life in the present), and a longing for God and salvation.

The time period of Romanticism also coincides with important political and economic changes in Europe and the Americas. Political revolutions of the late 1700s and early 1800s sought to give more rights to individuals. These revolutions included the American Revolution (1776), the French Revolution (1789-1792), the Revolutions of 1848 and the publishing of the Communist Manifesto, and the abolition of slavery and serfdom in Europe and the Americas. In these revolutions, the rights of the individual and their longing for freedom were valorized.

Another important context to consider when discussing the music of Romanticism is the Industrial Revolution, which had a tremendous impact on world economies, and on people’s daily lives. Within the Industrial Revolution, more people were making more money, creating a new “middle class” in society. The rise of this middle class meant that it was no longer just aristocrats and royalty who had disposable incomes and access to leisure activities, and the population of music lovers who could afford to attend concerts and take music lessons grew exponentially. To fill the demand created by this new middle class, art, literature, poetry, and music were created in greater quantities for people to enjoy in their homes.

Topics of Romanticism

Writers, artists, and musicians of the Romantic period chose to depict stories tied closely to the individual, and to emotional expression. However, unlike the popular plays and operas of the previous century, the plots of Romantic stories tended to end tragically, with elements of unfulfilled longing. The popularity of love stories exploded during this time, but often that love was unrequited, unreturned, or ended with the tragic death of one or both of the lovers, as in Wagner’s opera Tristan und Isolde.

Ruminations on death, religion, and the supernatural were also rife in Romantic music. In Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, the hero of the story falls in love, murders the object of his affection, is executed by guillotine, and then witnesses a witches dance in the afterlife. The most common type of Mass to be written during the Romantic period was the Requiem Mass, also known as the Mass for the Dead. Many composers of time provided at least one Requiem Mass as part of their catalogue of works.

In connection to the political changes happening during the period, many composers took part in political movements and wrote pieces to celebrate their country or national identity. Such pieces are a part of the movement known as Nationalism. One musical example of Nationalism is Bedřich Smetana’s cycle of six symphonic poems titled Má Vlast (or, My Homeland). Each symphonic poem from Má Vlast depicts various aspects of Czech landscape, history, or legends, all common preoccupations of the nationalist mindset

Additionally, in connection with Nationalistic depictions of various natural spaces, and also in reaction to the Industrial Revolution, many composers focused on composing music to depict natural landscapes, both from their current time and from an idealized past. For example, Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony no. 6, also known as the Pastoral Symphony, depicts the German countryside through which he would walk. The individual movement titles from this symphony include: “Awakening of cheerful feelings on arrival in the countryside,” “Scene by the brook,” “Merry gathering of country folk,” “Thunder, Storm,” and “Shepherd’s song.”

Musical Traits of Romanticism

Composers brought their musical narratives to life in sound by making each work a unique expression of emotions, creating organic unity for each piece, breaking the rules of form established in the Classical Period, using more dissonance, and expanding instrumentation.

In the Romantic period, for the first time, it was taboo for composers to recycle their own musical material in new works. Composers like Johann Sebastian Bach, George Friedrich Handel, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart would frequently take entire chunks of music from their early works and rework them in later pieces. During the Baroque and Classical periods, this was entirely acceptable, and helped composers to write vast amounts of music very quickly. However, with the new emphasis on individualism and the individual’s emotions in the Romantic period, composers risked ridicule if the material for each piece was not new. The effects of this trend can be seen in the numbers: Mozart and Haydn, both of whom recycled musical material in their works, composed 41 and 109 symphonies respectively, whereas Beethoven, who insisted on writing new material each time, only composed 9.

This emphasis on individual expression and uniqueness also led to the rise of the “genius” composer, who was, traditionally, a misunderstood soul in possession of great wisdom to impart to the world through their music. The framing of a composer as misunderstood and struggling against the world is a very Romantic idea and can be seen in the biographies of Romantic composers like Beethoven, Robert Schumann, Richard Wagner, and Gustav Mahler.

One way composers created unique, individual works was by connecting the movements of works through an organic unity. “Organic unity” is a fancy way of saying that works with multiple movements, like symphonies, operas, and sonatas, were tied together with a recurring melody or “theme.” An example of this is the four-note “fate” motif from Beethoven’s fifth symphony. Not only is the first movement of the symphony centered around those four notes, but the motif comes back in all the subsequent movements as well. These unifying themes were called different things by different Romantic composers. For example, Berlioz called this an “idée fixe,” while Wagner called it a “leitmotif,” a term still in use today.

Composers of the Romantic Period often relied on the forms established in the Classical period, but they also made changes to these forms to encompass their expressive musical interests. One way Romantic composers broke the rules of the Classical style was by expanding forms--making them longer and adding lengthy introductions, longer developments, and dramatic closing codas to individual movements. These expansions took the balanced, two-part Classical Sonata Form and turned it into a three-part form, with the development section gaining in emotional intensity and added length. Additionally, composers during the Romantic period modulated to a wider variety of key areas than those in the Classical period, adding more dramatic tension in the process.

19th Century Sonata Form

| Slow Intro | Exposition | Development | Recapitulation | Coda | |||

| A | B | A’ | |||||

| Primary Theme (Pt) | Secondary Theme (St) | Closing Material (K) | Pt St K | ||||

| Major | I | i, V, VI, III | I | Unstable key areas | I I I | I | |

| Minor | i | V, v, VI, III | i | Unstable key areas | i i i | i | |

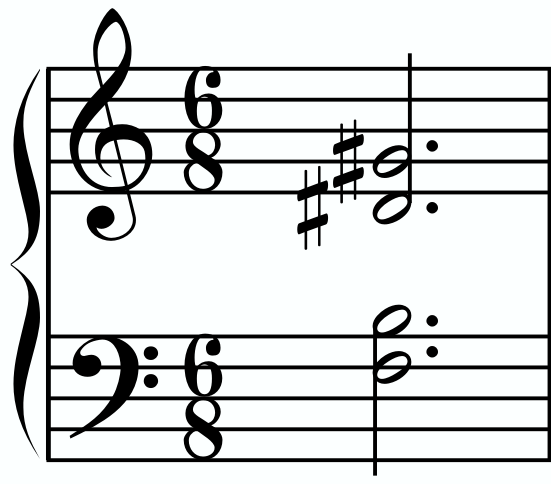

Composers further enhanced the dramatic tension of their works through the increased use of dissonance and unconventional harmonic relationships. A great example of such dissonance can be found in the famous “Tristan” chord used in Wagner’s opera Tristan und Isolde. This chord contains the dissonant interval of a tritone, an augmented 6th, and a raised 9th above the bass:

Wagner’s “Tristan” Chord

In Classical music, a dissonant chord like this would almost always occur in passing, and would resolve to a familiar, stable harmony, instead of the less stable Dominant chord it resolves to in Wagner’s opera.

Finally, composers expanded the instrumentation they used in their compositions. This included increasing orchestra sizes to have larger string sections, and employing winds in groups of three instead of the pairs found in orchestras of the Classical period. Composers also added higher and lower instruments to the orchestra to increase its pitch range. In the Romantic period, it was common for symphonic works to use piccolo, English horn, bass clarinet, contrabassoon, trumpets, trombones, and even tubas! Some symphonic works were also joined by full choruses, as in Berlioz’s dramatic symphony Romeo and Juliette.

The range of the piano was also expanded in the Romantic period, increasing in size from a four to five octave range to the modern day seven-octave range, an expansion that was well-exploited by piano-centric Romantic composers like Frederic Chopin and Franz Liszt. Pianos also acquired a more robust construction process, and were made using stronger materials like steel and cast-iron, giving them the ability to play louder, and giving composers the ability to reach for even greater dynamic extremes.

Contexts for the Romantic Period

Concert Life

Concert life flourished during the Romantic Period. The public concerts that had been gaining popularity in the Classical Period exploded in the early decades of the 19th century. Governments, as well as music societies, established concert series to be held throughout the year in a variety of venues. Large concert halls were erected to accommodate large performing orchestras and huge audiences. Composers could now earn money from the performance and publication of their works for such public concerts, rather than through composing solely for noble patrons or churches.

Public concerts also took on numerous forms. The majority of public concerts, those that were not opera performances, took the form of variety shows, in which many performers would perform many different styles of music. Performances could start with an orchestral overture, then have a singer performing an aria from an opera, then a violinist performing a romance, a pianist performing virtuosic transcriptions from a popular opera, a speaker reciting poetry to musical accompaniment, and a choir, all performing together as a part of a single concert.

The nineteenth century also saw the rise of the virtuosic performer, which led to the format of the solo recital with which we are familiar today. Performer composers would write works to show off their brilliant technique and astound their public audiences. One of the first of these virtuosic showmen was the violinist Niccolò Paganini (1782-1840), who wowed his audiences with brilliant displays of virtuosic musicianship--fast passage work, double stops, harmonics, and pizzicato effects. Rumors swirled around Paganini, stating that in order to be so good at the violin, he must have sold his soul to the devil, a rumor that also followed many other virtuosic performers into the twentieth century.

Audience fandom for virtuosic performers lead to the Romantic “Cult of the Artist,” which elevated particular composers and performers to the level of “vaunted genius.” This fandom is similar to what we see in the twentieth century with big name celebrities like The Beatles, Elvis, Taylor Swift, Justin Bieber, and One Direction. Audiences would flock to concerts, strive to meet the artist, and buy merchandise adorned with the artists’ names. Two of the biggest stars of the nineteenth century were pianist Franz Liszt and opera singer Jenny Lind, who generated their own special brands of fan devotion, “Lisztomania” and “Lindomania.” Products sold with Jenny Lind’s name on them included: cribs, chairs, stools, ovens, fireplaces, perfumes, soaps, dolls, as well as songs and sheet music.

Additionally, the Romantic Period witnessed a change in audience behavior during concerts. In the Classical and early Romantic periods, audience members would converse, dance, and eat while a concert was being performed. Audiences would often cry out with cheers or boos, depending on their appreciation of what was being performed. As the nineteenth century continued though, new restrictions were added to concert halls, which called for the audience to sit quietly and receive the “emotional wisdom” from the composers and performers on stage.

Music for the Home

Domestic music-making similarly experienced a large boom during the Romantic Period. As mentioned earlier, due in large part to the Industrial Revolution, Europe and the Americas gained a new middle class that possessed leisure time and a degree of disposable income. In a world without TV’s and smartphones, one of the most popular uses of leisure time and disposable income was for music. Families hired music teachers for their children; sons would learn how to play string or wind instruments and daughters would learn to sing and play piano. In fact, it was considered a sign of a family’s elevated social status to have a daughter who could play piano for the family’s entertainment. To fill the demand of such private performances, composers wrote in more intimate genres like the German Lied (song), character pieces for solo piano, sonatas for a solo instrument and piano, and piano trios.

Famous composers and performers also participated in home music-making for their close friends and family. The composer Franz Schubert held renowned “Schubertiads” where he would perform some of his latest compositions, and host friends and family in the reading of poetry and in the debate of political issues. Pianist and composer Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel also hosted musical performances every Sunday in her family’s Berlin home. Performances at Hensel’s musicales could include full orchestral performances, choirs, as well as performances of chamber music and solo instrumentals. Some notable attendees and performers at Hensel’s musicales included composers Robert and Clara Schumann, virtuoso violinist Joseph Joachim, the composer Johannes Brahms, and of course, Hensel’s brother, Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy. The room these concerts were held in could fit up to one hundred people, but since they were held in a private home and for only those invited, they were still seen as private, domestic performances.

Music was an essential form of entertainment in both the home and in public life during the Romantic period. At the end of the 19th century, new technologies, such as the invention of recorded sound and images, would have a major impact on daily life. Composers of the Early Modern period to come in the beginning of the twentieth century would have to grapple with these changes and invent new ways of perceiving and creating music.

Check out this list of major Romantic composers to learn more:

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809-1847), Amy Beach (1867-1944), Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827), Vincenzo Bellini (1801-1835), Hector Berlioz (1803-1869), Georges Bizet (1838-1875), Johannes Brahms (1833-1897), Cécile Chaminade (1857-1944), Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849), Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904), Mikhail Glinka (1804-1857), Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829-1869), Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel (1805-1847), Franz Liszt (1811-1886), Gustav Mahler (1860-1911), Giacomo Meyerbeer (1791-1864), Modest Mussorgsky (1839-1881), Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924), Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868), Franz Schubert (1797-1828), Clara Schumann (1819-1896), Robert Schumann (1810-1856), Bedŕich Smetana (1824-1884), Richard Strauss (1864-1949), Arthur Sullivan (1842-1900), Piotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893), Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901), Richard Wagner (1813-1883), Carl Maria von Weber (1786-1826)

And here are some musical examples to help you explore the sounds of Romanticism:

Musical Examples from this Period

Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel: Schwannenlied

Franz Schubert: Gretchen am Spinnrade

Fryderyk Chopin: Nocturne in D-flat Major, Op. 27, No. 1

Robert Schumann: Waldszenen Op. 82, No. 7: Vogel als Prophet

Clara Schumann: Piano Trio, Op. 17

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy: Violin Concerto in E Minor

Franz Lizst: Piano Concerto No. 1 in Eb major

Hector Berlioz: Symphonie Fantastique, movement 5: “Witches Sabbath”

Johannes Brahms: A German Requiem

Vincenzo Bellini: “Casta Diva” from Norma

Giuseppe Verdi: “Che Gelida Manina” from La Bohème

Thanks for reading! Keep an eye out for more articles on music history, and for our Composer Bios article series, where we will survey the lives and music of your favorite classical composers.

We made a video tutorial to go with this article, check it out.