The Classical Period follows the Baroque and lasts approximately from 1750 to 1820. Many of the traditional practices of Western Music as we know it were codified during the Classical Period - a reflection of which can be found in the name itself. Synonyms for classical include “authoritative” and “traditional” - fitting adjectives for the period that established many of the rules that composers follow even today!

In everyday conversation, “classical music” is a catch-all term for any music that is not Pop, World, or Jazz music. Generally, what people actually mean when they say classical music is “music of the Western Art Tradition.” “Western Art Music” includes music made from the Middle Ages through the 21st century in Western Europe, North America, and other continents with a history of European colonization. What we’re talking about in this article is the specific time period of that tradition that has been labeled by music historians as the “Classical Period,” lasting from around 1750 to around 1820.

Composers, musicians, and audience members during the Classical Period were reacting to the musical trends of the Baroque Period, which was known for its highly decorated melodies, complicated textures and structures, and emotional extremes. As a response, composers in the Classical Period used Baroque genres but focused on formal balance along with memorable and singable melodies.

Forms and Genres of the Classical Period

Many of the forms and genres invented during the Baroque Period were adapted to fit these new aesthetic sensibilities. Examples of these include the Baroque French opera overture which evolved into a stand-alone four movement symphony, Baroque Trio Sonatas with basso continuo, which evolved into Classical string quartets, and sonatas for solo instruments, which became standardized in their movement tempos and key relations. These newly standardized forms became the authoritative versions that musicians continue to expand upon.

Symphonies and String Quartets

The technique of counterpoint carried over from the vocal polyphonic practices of the Renaissance era and reached some of its greatest heights under the quills of the Baroque composer. In contrapuntal compositions, multiple lines of musical material (melodies) are woven together as independent and equally important “voices.” Check out this example, from Johann Sebastian Bach’s Prelude and Fugue in C-sharp minor, BWV 848.

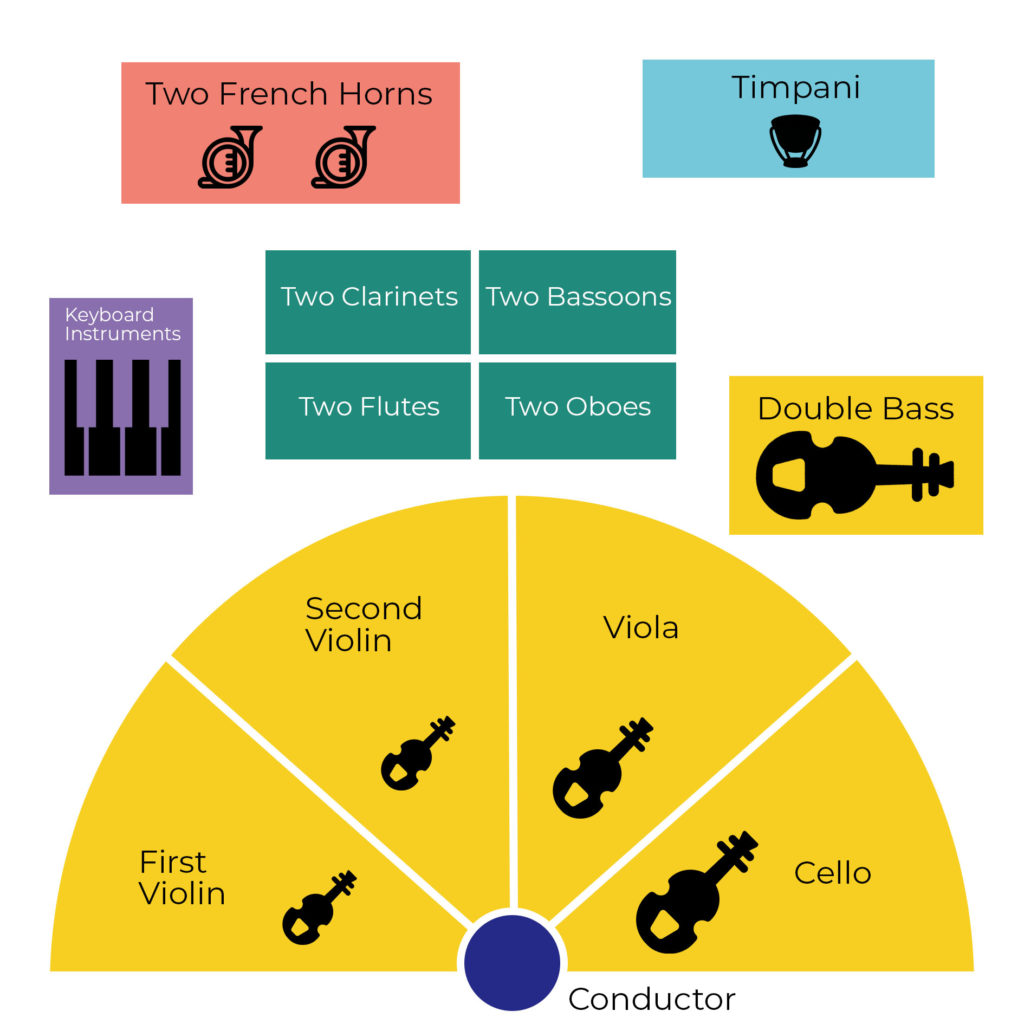

The genres of the orchestral symphony and string quartet began during the Classical Period and became essential genres for many composers. Orchestral instrumentation likewise became standardized during the Classical period, as opposed to earlier periods where composers would simply write for whatever instruments were available at their church or court. Classical Period symphonies become standardized as having a medium string section in four voices:

1st Violin - 2nd Violin - Viola - Cellos and Basses

And additionally included wind instruments in pairs:

2 Flutes - 2 Oboes - 2 Clarinets - 2 Bassoons - 2 French horns - Timpani for percussion

Early string quartets were closely related to early symphonies, with many compositions able to be performed by a string section of the orchestra or by a string quartet featuring a similar organization of voices:

1st Violin - 2nd Violin - Viola - Cello

Most commonly, early string quartets and similar chamber music were performed in parlors for the entertainment of the players and close friends--many of which involved amateur players who also happened to be emperors, kings, and princes. For example, Haydn wrote many works in which his patron, Prince Nikolaus Esterházy I (1714-1790) played the baryton (a large string instrument related to the string bass). Prussian King Frederick the Great (1712-1786) was also an avid flautist and composer who used music for courtly events as well as personal entertainment. Later string quartets became important vehicles for virtuosic showmanship, requiring greater levels of skill to successfully perform.

Sonatas

During the Baroque period, solo instrumental sonatas became an important vehicle for individual instrumental expression. In the Classical Period, sonatas became standardized as a three movement genre (Fast-Slow-Fast) and each movement had specific forms to follow. A good example of a typical sonata from this period is Mozart’s Sonata No. 10 for Piano, K. 330. This sonata takes place over three movements, with a fast Allegro moderato first movement, a slow Andante cantabile second movement, and another fast Allegretto third movement.

Common Forms of the Classical Period

Let’s look at the movements from this Mozart sonata in greater detail to examine the expected forms:

Sonata Allegro Form

The first movement of the Sonata is in the Classical version of Sonata Allegro form, which developed out of the rounded binary form of the Baroque period. The Classical Sonata Allegro form has an A B A’ outline, with the first A section, called the “Exposition,” consisting of a first theme that’s composed in the primary key of the piece, a second theme written in the Dominant key or relative major key, and then a conclusion back in the tonic key. The entire exposition then repeats, and enters the B section, called the “Development,” where the themes are manipulated in various ways and through various other keys. Finally, we return to the A section material in the last section, the “Recapitulation,” which is altered harmonically to land on a final cadence in the home key. In Classical Period Sonata Allegro Form, the Development and Recapitulation are repeated, as shown in the diagram below.

| Exposition | Development | Recapitulation | |||

| 𝄆 A 𝄇 | 𝄆 B | A’ 𝄇 | |||

| Primary Theme (Pt) | Secondary Theme (St) | Closing Material (K) | Pt St K | ||

| Major | I | V | I | Unstable key areas | I I I |

| Minor | i | V | i | Unstable key areas | i i i |

For more on sonata form check out the article - “What is Sonata form?” on the Liberty Park Music blog.

Ternary Form

The second movement from this sonata is slow and songlike with the marking “cantabile” (or “songlike”), as is expected of the second movements of sonatas. In addition, this movement follows the Baroque Ternary form adapted from Da Capo Arias in opera.

| A | B | C | D | A | B | |

| a a’ | b b’ | c c’ | d d’ | a | b | |

| Major | I | V - I | x* | x* - I | I | I |

| Minor | i | V - i | x* | x* - i | i | i |

*x in this diagram means that the key is neither the tonic or dominant, but can be some closely related key.

Rondo Form

The final movement from our Mozart example is another lively Sonata Allegro Form; however, final movements of sonatas could be either Sonata Allegro Form or Rondo Form. Rondo form consists of repeating A material separated throughout the movement with areas of contrasting or developmental material. The A material serves as a main, anchoring theme that comes back throughout the movement, and is known as a “ritornello.” The contrasting “episodes” between ritornellos are shown here in the B and C sections.

| A | B | A | C | A | B | A | |

| Major | I | V | I | x* | I | I | I |

| Minor | i | V | i | x* | i | i | i |

*x in this diagram means that the key is neither the tonic or dominant, but can be some closely related key.

Binary Form and Rounded Binary Form

Another common form used during the Classical Period in compositions with multiple movements is the Binary or Rounded Binary Form. In four-movement sonatas, symphonies, and string quartets, these binary forms could be used for second or third movements.

Binary Form

| 𝄆 A 𝄇 | 𝄆 B 𝄇 | |

| a a’ | b b’ | |

| Major | I | V - I |

| Minor | i | V - i |

Rounded Binary Form

| 𝄆 A 𝄇 | 𝄆 B 𝄇 | |

| a a’ | b b’ a | |

| Major | I | V - I |

| Minor | i | V - i |

It’s important to note here that Binary Form and Rounded Binary form get used in almost every genre of Classical Period music!

Tonality

As noted in the diagrams for these movements, each section moves through specific key areas. While some Baroque music used the same key areas in their sonatas, the system of tonality that was codified during the Classical Period was not written out until Jean Philippe Rameau’s Treatise on Harmony in 1722. In his treatise, Rameau incorporated mathematics to argue for a harmonic gravity, whereby a “fundamental bass” served as the musical ground from which all harmonic movement originates and must necessarily return to by the end of a piece. Rameau coined the terms “tonic,” “dominant,” and “subdominant” to represent the I, V, and IV chords of a key and the goal of harmonic progressions to lead back to I. Much of Baroque music, while using some of the tonal practices laid out in Rameau’s Treatise would still be considered modal rather than tonal, and the core principles of tonality as we know it became much more prominent during the classical era.

Classical Textures

Homophonic textures with individual melodies and chordal accompaniment predominate in Classical Music, due in large part to the period’s emphasis on chordal harmonic progression over contrapuntal line development. This emphasis on melody also leads to instrumental melodies that move more in stepwise motion, with fewer leaps than in the Baroque Period. The results of this were tuneful melodies that audience members could remember and sing long after a performance had ended.

Public Concerts

These tuneful melodies and simpler textures also appealed to a rising population of new audience. During the late Baroque Period, public concert houses were being established for the first time, allowing more people to hear concert music. The number of public concert houses with a ticket-buying audience increased in the Classical Period, and became an important way for composers and musicians to support themselves. Finally, musicians no longer had to rely solely on the Church or Court to perform their music, and the practice of writing music for public concerts - a practice that serves as the origins for today’s concerts and live performances - was born.

Check out this list of major Classical composers to learn more:

Thomas Arne (1710–1778), Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714–1788), Johann Christian Bach (1735–1782), Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827), Luigi Boccherini (1743–1805), Domenico Cimarosa (1749–1801), Muzio Clementi (1752–1832), Christoph Wilibald Gluck (1714–1787), François-Joseph Gossec (1734–1829), Joseph Haydn (1732–1809), Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791), Antonio Rosetti (1750–1792), Antonio Salieri (1750–1825), and Giovanni Battista Sammartini (c. 1700 – c. 1775)

Of course, listening to musical examples is the best way to truly learn about a musical style, so here are some musical examples from the Baroque period for you to enjoy:

Musical Examples from this Period

- Haydn: Piano Sonata No. 50 in D Major

- Haydn: Symphony No. 45 in F# Minor, “Farewell”

- Mozart: Piano Sonata No.10 in C Major, K. 330

- Mozart: Symphony No. 41 in C Major, “Jupiter,” K551

- Mozart: Opera - “Papageno-Papagena” from The Magic Flute

- Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in Eb Major, “Eroica”, Op. 55

- Beethoven: String Quartet No. 7 in F Major, Op. 59

- Beethoven: Piano Sonata No. 8 in C Minor, “Pathétique,” Op. 13

Thanks for reading! Keep an eye out for more articles on music history, and for our Composer Bios article series, where we will survey the lives and music of your favorite classical composers.