The piano is a “harmony” instrument, meaning that we can play many notes at once. Certain combinations of notes give us harmonies that we call chords, and the ability to play chords is an important skill, no matter what style of music you’re playing. One of the most efficient routes to knowing which chords to play is by having the ability to read chord symbols.

In this article, we’re going to teach you how to read chart-style chord symbols. Along the way we’re going to reinforce our understanding of what chords are and how they’re built.

As a bonus, we have a downloadable chart of all of the chord symbols covered in this article alongside their notated counterparts! Just click the link at the end of the article to download.

A Brief Reminder: What are chords?

Chords happen when two or more notes are played at once.

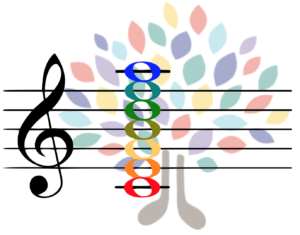

We think about building chords in thirds, starting with a “root,” which is the main note from which we name the chord or harmony. When you stack two more thirds on top of the root, each a third above the other, we get our core triad. On top of the core triad, another third can be added to give us a 7th, and we can continue this way into higher extensions, or “color” tones. Think of a fully filled out chord as being like a tree, with the roots and trunk on the bottom, the heavier, sturdier branches in the middle, and the more delicate branches and leaves on top:

Most of the chords you will see will only feature the root and trunk of the tree (the core triad and the 7th); however, the presence of the higher “color” tones is not unusual.

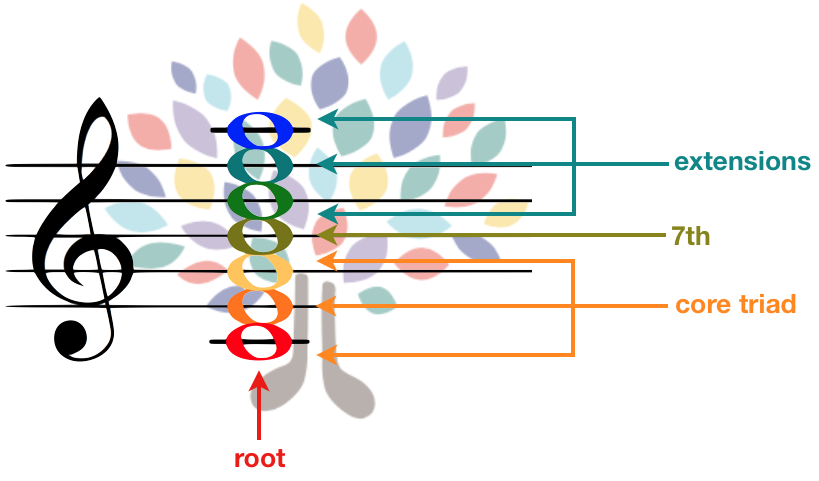

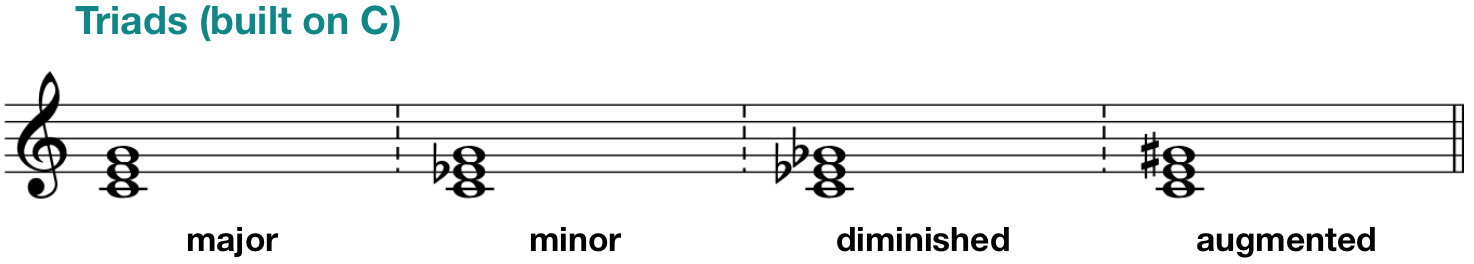

Manipulating the thirds that form the trunk of the tree alters the identity of the chords. For example, if we have a triad with a major third on the bottom and a minor third stacked on top of it, we get a major triad. Conversely, if the minor third is on the bottom and the major third is on top, we get a minor triad. Two minor thirds stacked on top of each other make a diminished chord and two major thirds stacked on top of each other make an augmented chord:

When any of the triads above make up the bottom three notes of the chord, they form that chord’s core identity triad, which is the primary quality of the chord and the place from which we derive the chord’s name (major, minor, diminished, augmented).

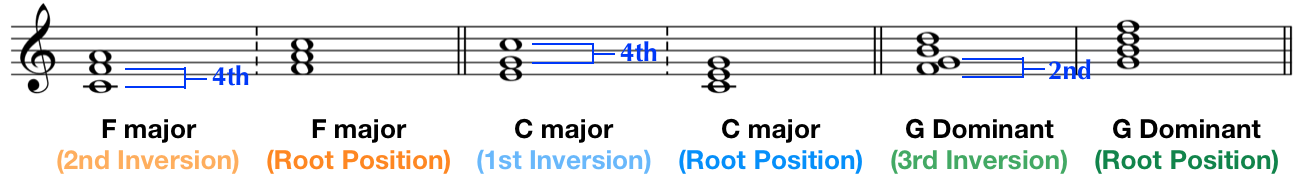

Chords are always named based on the most complete configuration of their thirds, which is called root position. This means that if you see a chord with a 4th or a 2nd in it, it is not in root position; you will need to reorient it back into root position to figure out its name and quality.

Chords are commonly found in positions other than root position, called inversions. We know we are in an inversion of a chord if a note other than the root is in the bass.

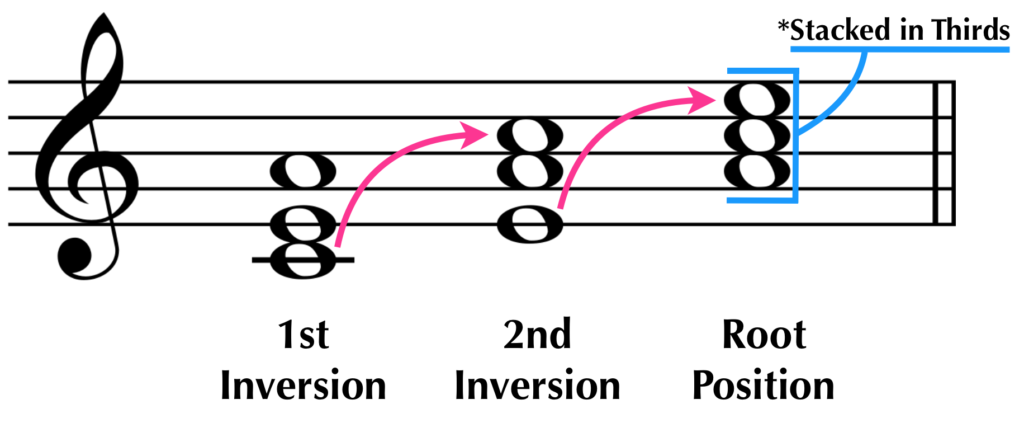

Including root position and all inversions, chords have as many positions as they have notes. For example, a three-note triad has three total positions (root position, 1st inversion, and 2nd inversion), while a four-note 7th chord will have four (root position, 1st inversion, 2nd inversion, and 3rd inversion). Chord inversions are numbered as they progress upward: if the 3rd of the chord is on the bottom, it’s a 1st inversion, if the 5th is on the bottom, it’s a 2nd inversion, etc.

A trick you can use to find the root position of a chord is to keep flipping the bass note up to the the top until you can stack the chord in thirds:

Being able to determine that a chord is in an inversion and convert it back into root position is a valuable skill for identifying chords as quickly as possible.

Here are some examples of inverted chords alongside their root position counterparts:

It’s important to remember what chords are, how they’re generated, and how they’re named when learning to read chord symbols. As we’ll see, reading chord symbols is about being able to recognize what a chord is based on a minimal amount of information, so the more familiar you are with the basics, the better.

Let’s see how all of this applies when reading chord symbols.

Looking at Chord Symbols: Root Position

Chord symbols use letters and numbers to indicate what harmonies we should play in a given portion of music. The key difference between reading notated chords and reading chord symbols is that notated chords will tell you exactly what to play and when to play it, while chord symbols afford greater freedom and creative flexibility (as long as you know which notes are supposed to be played).

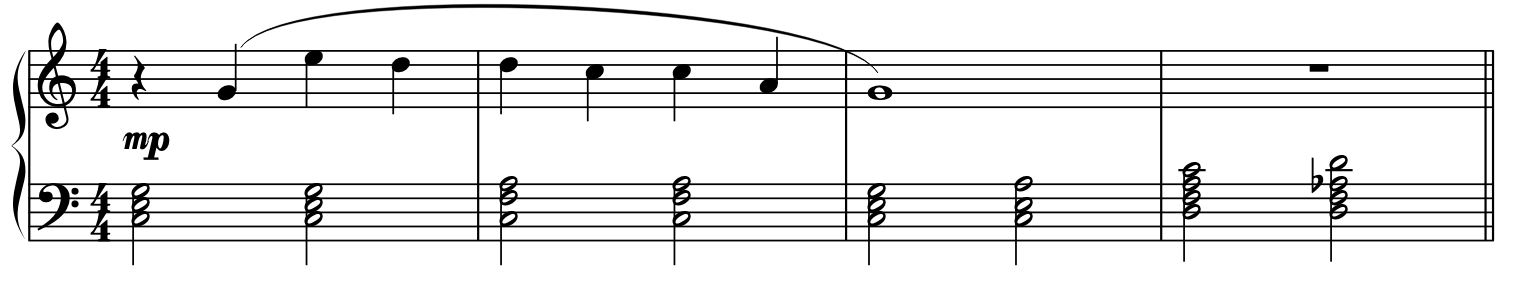

Below are two examples of the same melody, one with notated chords, and the other with just chord symbols. Listen to the differences between the chordal accompaniment:

As you can hear, in the first example I’m playing the chords exactly as written, but in the second example I’m generating not only the chords but also their rhythms based on my ability to interpret the chord symbols.

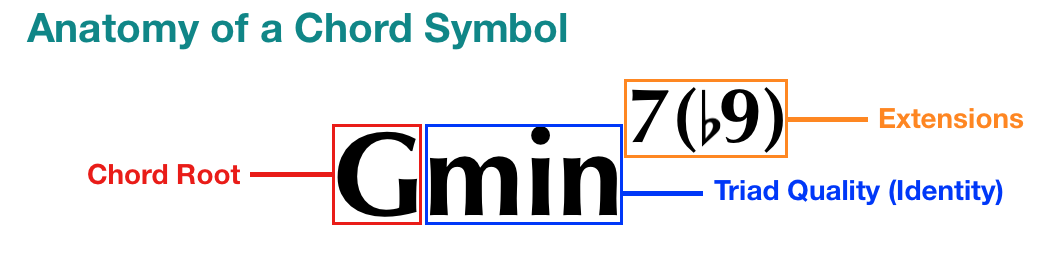

Let’s now take a look at the anatomy of a chord symbol to see exactly what it is that I’m thinking about when reading them:

The main letter and its qualifier indicate the core (root) triad identity of the chord (major, minor, diminished, or augmented), while the numbers on the upper right side indicate extensions of the chord, such as 7ths, 9ths, 11ths, and 13ths.

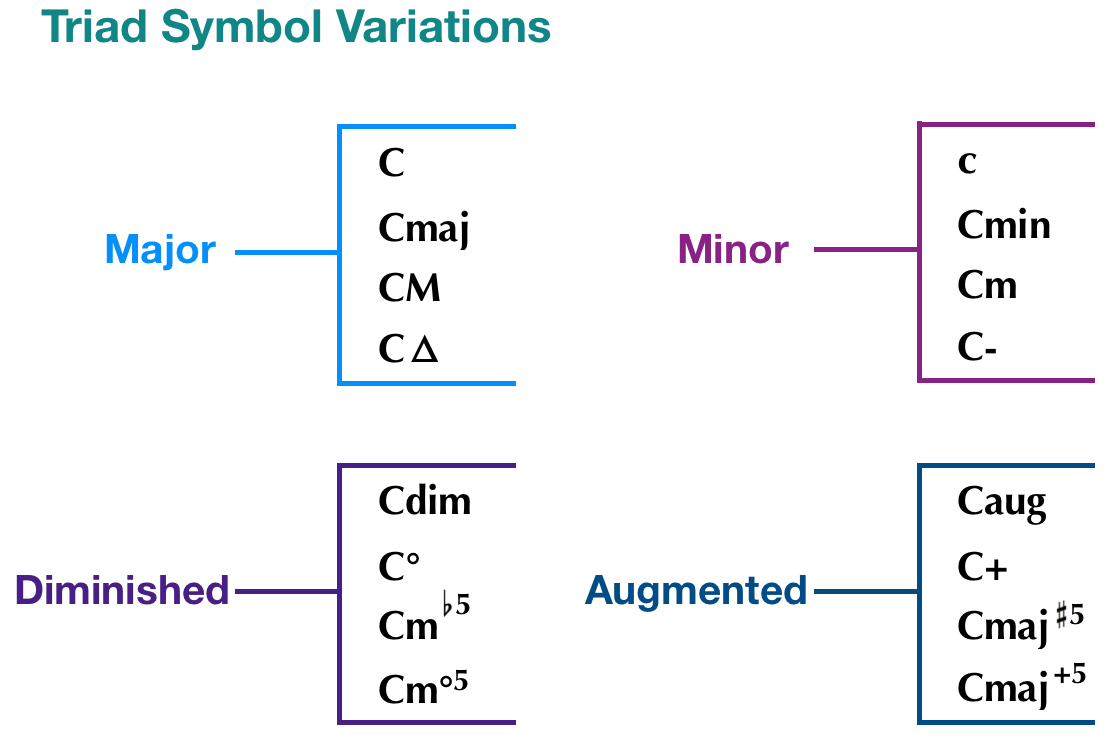

The symbols and abbreviations for triads can come in a number of different variations. For these examples, we will use C as our triad:

When we see a chord symbol, our first thought should be: What is the core triad? Then, we can consider what extensions it may have.

The most common extension you’ll see is the number 7, which indicates that there should be a 7th on the chord. You can think of adding a 7th to a chord like adding another third onto your triad stack.

7th chords are common enough to be considered a separate class from higher extensions like 9ths, 11ths, and 13ths. Some 7ths, like the Dominant 7th, play an important harmonic role, and have a more significant impact on the harmonic trajectory of the music. Others, like most Major 7ths, are more for adding color.

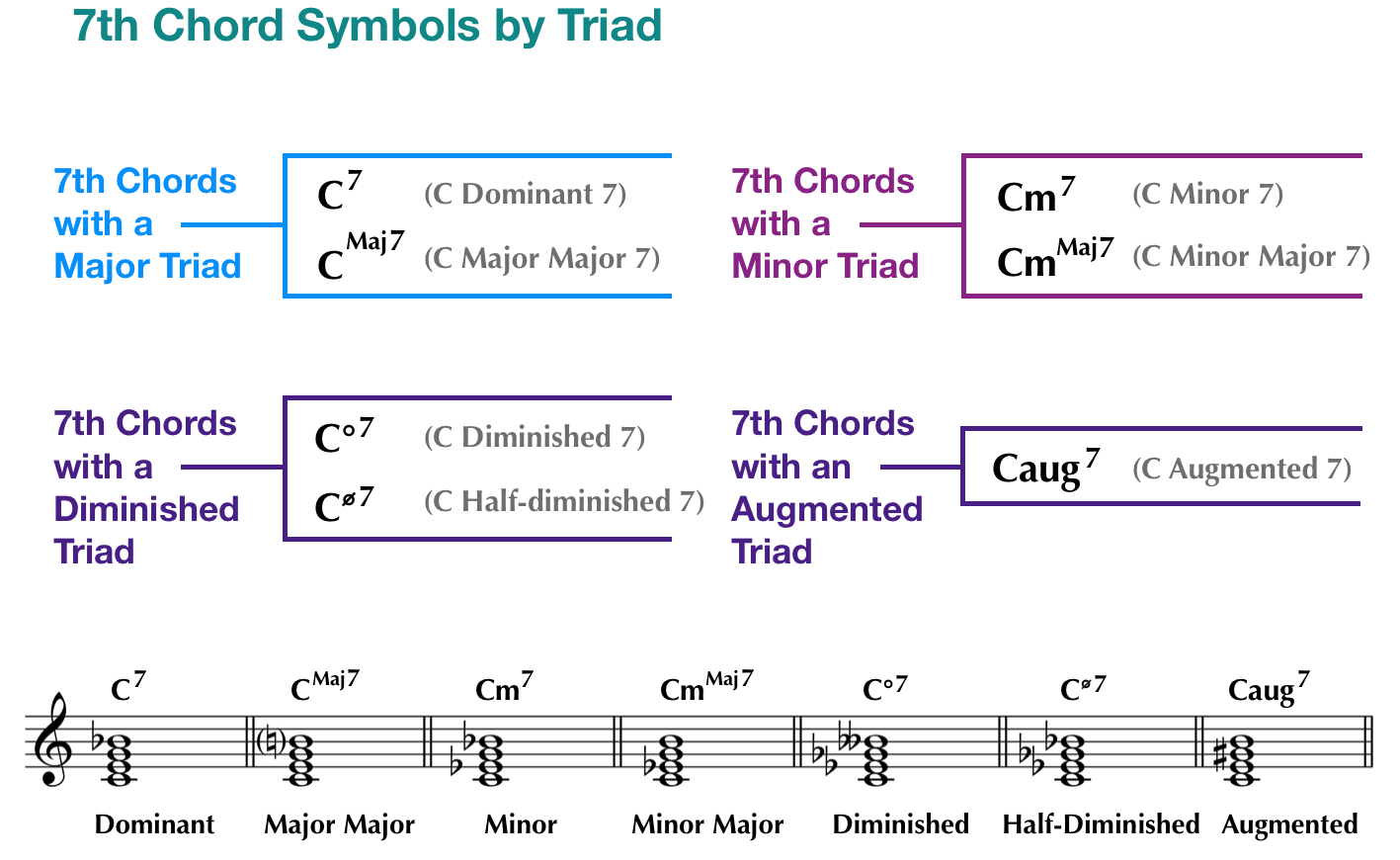

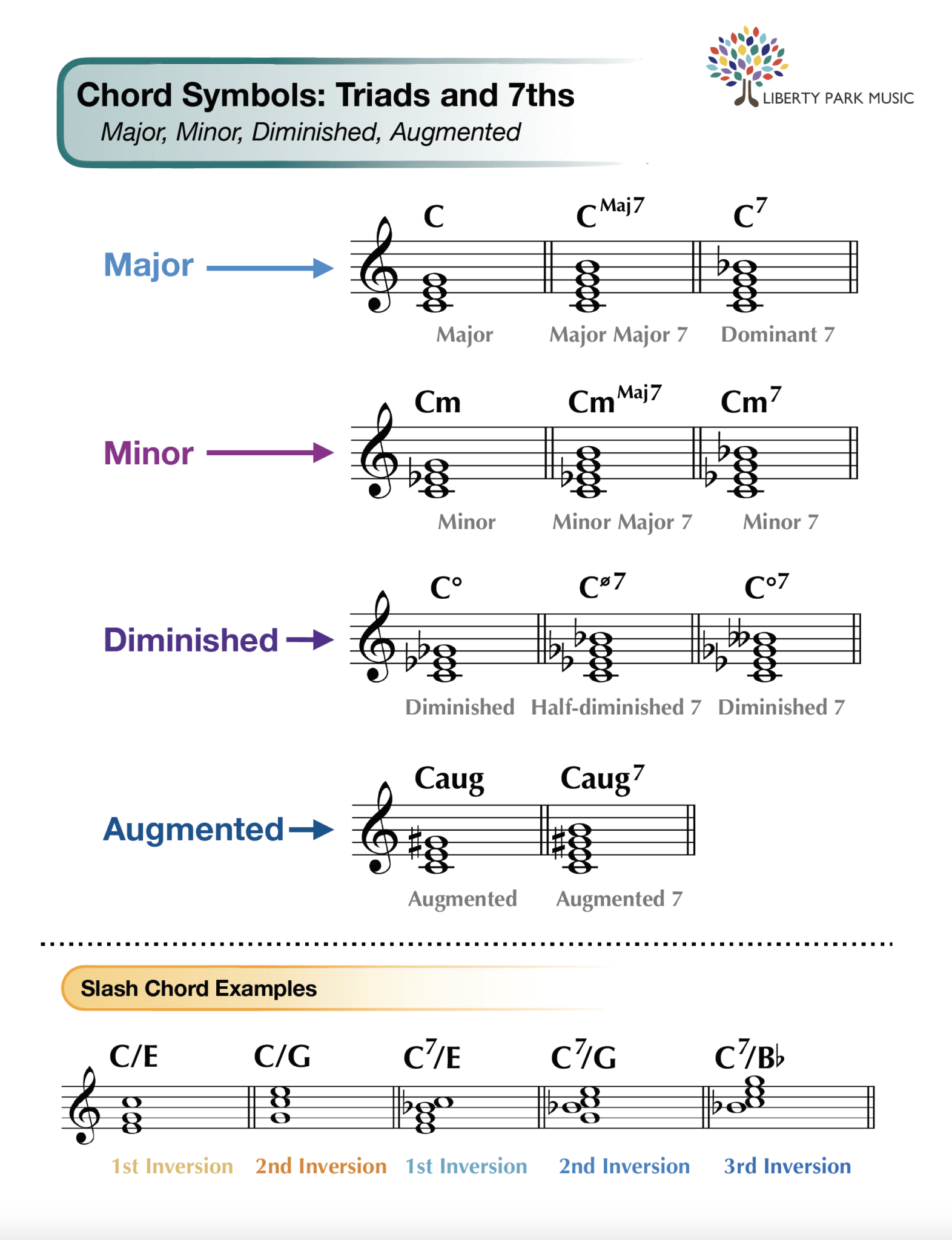

We can categorize the common types of 7th chords based on their core triad:

Be aware, we can see the same symbol variations regarding major, minor, diminished, and augmented when using 7ths. For example, you may see C°7 written as Cdim7.

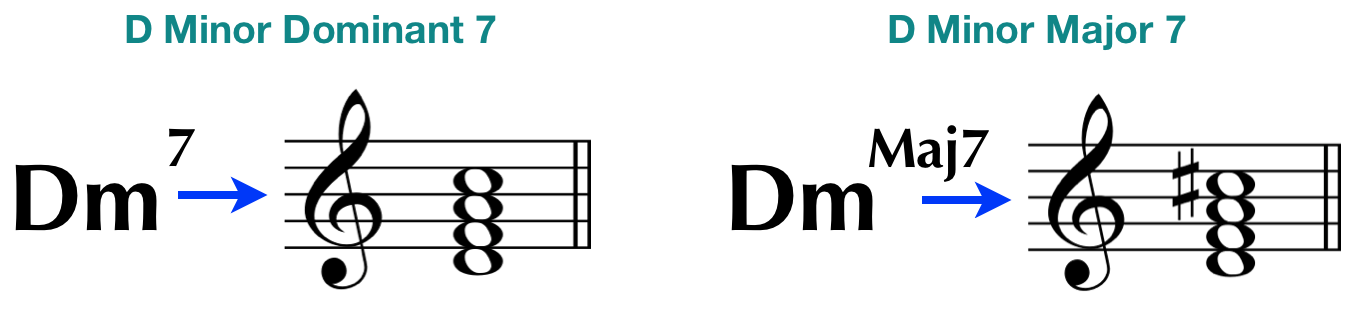

The most common kind of 7th chord is the Dominant 7th, which naturally has a lowered (or flatted) 7th. For this reason, chord symbols with a simple 7 attached to them are automatically assumed to have a lowered 7th.

If you want to know more about dominant and diminished, check out our article on the subject here.

Recall that a lowered, or “flatted,” 7th is a whole step lower than the root, while a raised or “major” 7th is only a half step lower. For example, if we have a D minor chord with a lowered 7th on it, our notes would be D, F, A, and C, which is a whole step down from the D above it. This is the configuration of notes we assume if we simply say “D minor 7.” If we want to have a raised 7th, we must indicate so in the chord symbol:

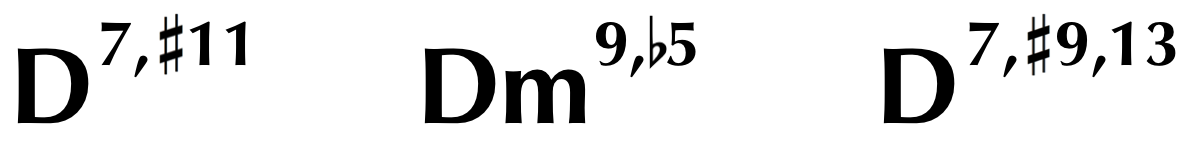

Further extensions can be included by adding the corresponding numbers to the top right of the letter symbol. Any modifiers to these extensions (sharps or flats) must go next to the extension numbers when they’re written, and they typically (but not always) extend from the main chord letter from smallest to largest:

Looking at Chord Symbols: Slash Chords

To reiterate, the most effective way to consider what chord symbols are is to envision the chords built up in thirds from their roots. However, as with notated harmonies, it is often more pleasing musically to have a note in the bass of the chord that is not the root. This can technically be any other note in the chord, but is usually the 3rd or 5th, and sometimes the 7th.

In notated music, we call these inversions. When seen using chord symbols, we call them slash chords.

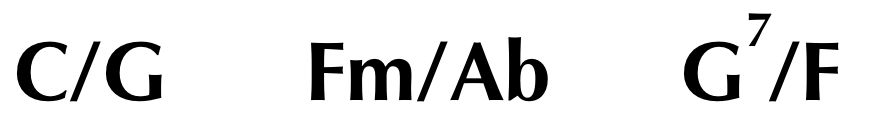

Let’s look at some slash chord examples:

As you can see, slash chords incorporate an additional letter into the chord symbol, separated by a forward slash. This means that the chord is to be played with the note featured under the slash (on the right side) as the bass of the chord.

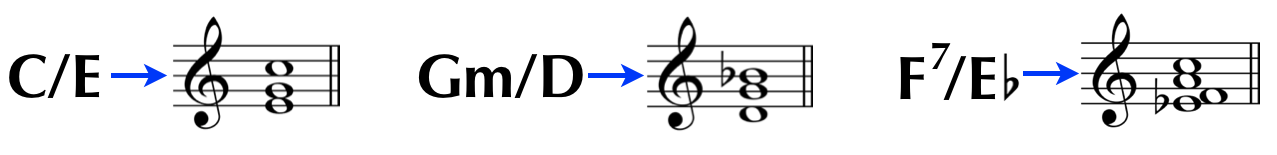

Let’s look at a couple of examples with their notated counterparts:

When spoken, the correct way to name slash chords is by using either slash or over. For example, the C/E chord symbol seen in the example above would be spoken: C slash E, or C over E, meaning over the bass note.

Remember, the root of the chord is still the note that would be on bottom if the chord were stacked in thirds, even if we’re using a different position of the chord that puts another note in the bass. This is important to memorize so that you don’t mistake the bass note in a slash chord for the root, and therefore mistake its identity.

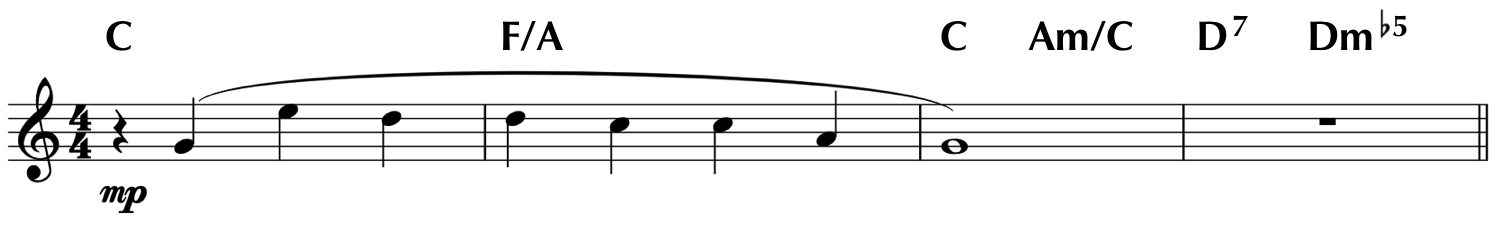

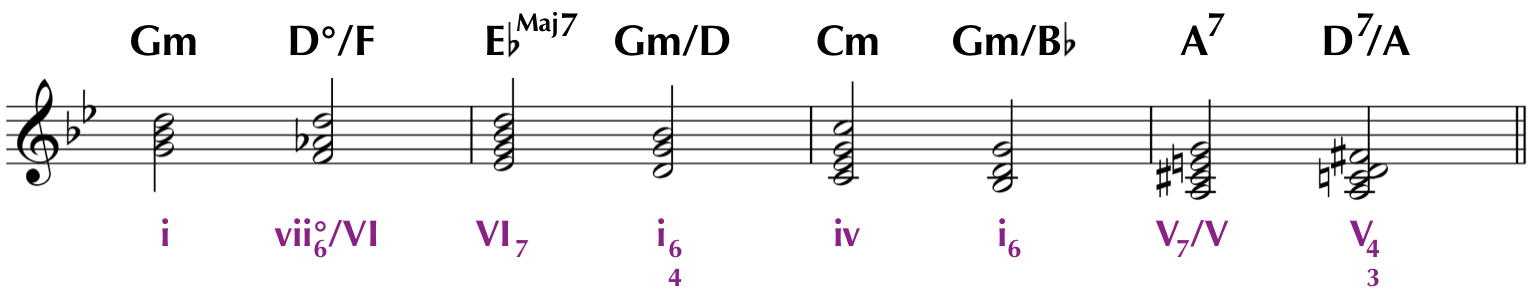

Let’s look at a few more examples of chord symbols in action:

The progression above has a series of descending chords, in both root position and inversions. Along with the notation, there are chord symbols above the staff, and a Roman numeral analysis below. Notice how the chord symbols mirror the chord inversions by using slashes to indicate the note in the bass, and compare the slash chord symbols with the Roman numerals. An important difference between chord symbols and Roman numeral analysis is that chord symbols simply state what the chord is and whether or not it is inverted, while Roman numerals also describe the functional relationship of the chord within the key.

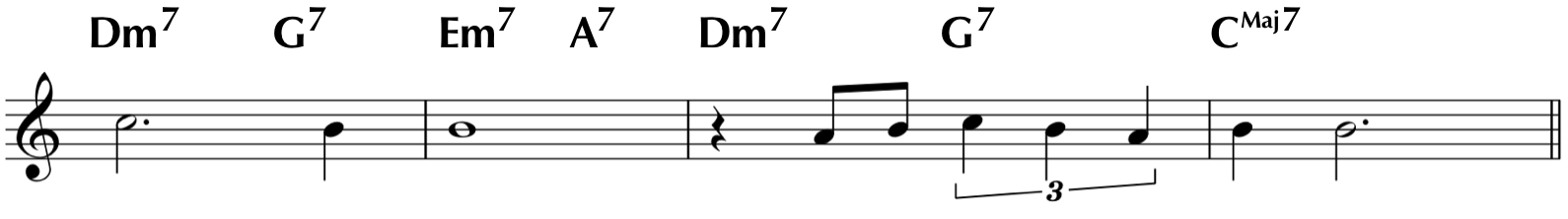

Let’s look at one more example of chords symbols, this time as they might be seen in a jazz chart:

In jazz charts, as well as in many pop song arrangements, it is common to only see the melody accompanied by chord symbols. Performers must know how to interpret the melody and the chord symbols together to generate the music. This approach demands more of the performer’s internal knowledge base, but also affords more creative fluidity in the moment, and allows for the structured freedom necessary for high-level group improvisation. To become competent at this, jazz musicians will exhaustively drill improvising and playing chord progressions in all different keys, so that they are in possession of a rich palette of musical tools to employ for whatever a chart demands.

Download and Further Reading

For your convenience, we've gathered all of the most important info from this article into one easy-to-read chart! Click the link below to open a downloadable PDF of all of the triads and 7ths chord symbols covered in this article.

Keep an eye out for our next article on chord symbols, in which we'll take a closer look at chord extensions, and explore the different ways we can play music by reading chord symbols.

And if you enjoyed what you learned, be sure to check us out at libertyparkmusic.com!