Since the 17th century, the Circle of Fifths has been a prominent tool utilized by professional musicians and composers throughout Western Culture.

Knowledge provided by the Circle of Fifths is practical for many situations and will become automatic with consistent practice.

Musicians such as Bach (Baroque), Beethoven (Classical), Schubert (Romantic), Jerome Kern (Jazz), John Williams (Film), Selena Quintanilla (Teejano), Lin-Manuel Miranda (Broadway), Beyonce (Pop), and Armin Van Buuren (EDM), are just a few whose music is built around the Circle.

The Circle of Fifths offers fundamental knowledge which can be applied to any genre or style of music.

In this article we will learn what The Circle of Fifths is, how to read it, how to use it to further our understanding of keys signatures, and how to apply it in music theory and composition.

What is the Circle of Fifths?: Reading the Clock

The Circle of Fifths is a great tool in aiding musicians to learn and memorize all the basic diatonic key signatures.

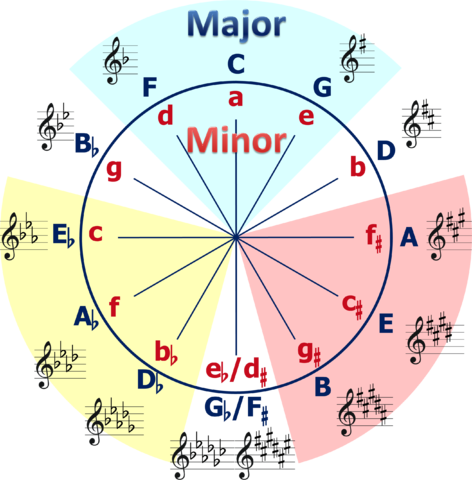

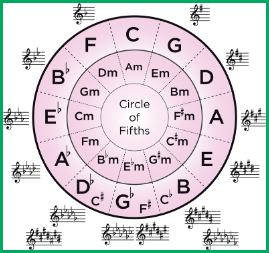

The diagram presents all the diatonic major and minor keys, in order, based on the amount of sharps or flats.

It can be thought of as the analog clock of music. Like an analog clock, the Circle of Fifths is divided into 12 points, but instead of numbers, there are letters. Whereas the numbers on the clock represent hours of the day, the letters on the clock represent the prominent major and minor key signatures in Western music!

If we start at the top of the circle, 12 o’clock on an analog clock, we can begin counting clockwise 1, 2, 3, just like an analog clock. The sharp keys move by perfect fifths, and are placed clockwise around the circle.

What's cool about the sharp keys is that one sharp starts on the number one, and moves up accordingly. The flat keys move by perfect fourths, and are placed counter-clockwise, starting at 11 o’clock, around the circle--adding a flat with each counter-clockwise move.

The Key Signatures

As mentioned above, the arrangement of the key signatures in the Circle of Fifths is based on the number of sharps or flats in each key. There are 7 sharp keys and 7 flat keys. However, the top of the Circle, 12 o’clock, is our neutral key, meaning no sharps or flats: C Major.

Enharmonic Keys

If the Circle of Fifths only has 12 spots, how can there be 7 sharp and 7 flat keys, plus our neutral key of C Major? The answer is, three of these keys are Enharmonic.

Enharmonic Keys are key signatures that have the same pitches, but different names. These keys are: B Major/Cb Major, F# Major/Gb Major, and C# Major/Db Major. These three sharp/flat keys are technically the same on the keyboard, and have the same spot on the Circle of Fifths, but they can be identified with two different names and function differently in music and aural theory.

Sharp Keys

Let's start by reading above the diagram clockwise starting on C major: G Major, D Major, A Major, and E Major, B Major, F# Major, and C# Major. Notice that it starts with one sharp, and increases by one sharp as we go around the clock, all the way to having a key signature with 7 sharps.

Flat Keys

If we go back to C, and read the clock counter-clockwise the same principle is applied, but with flats: F Major, Bb Major, Eb Major, Ab Major, Db Major, Gb Major, and Cb Major.

Relative Minor Keys

All major key signatures, sharps and flats, have a relative minor signature that shares the same number of sharps or flats.

To find the relative minor of a key signature, you can do one of the following two. Either: go down three half-steps from the major keys tonic note, or go to the sixth note in that key signature’s scale. Either way, you will end on the relative minor for that major key.

Ex: C Major: three half-steps down~B/Bb/(A): A minor, or the sixth in the scale~C/D/E/F/G/(A): A Minor.

Remember: We have our neutral key C major, seven Sharp Keys, and seven Flat Keys. Three of these keys are Enharmonic Keys, resulting in four independent Sharp and Flat Keys.

Keep in mind that every major key signature has a relative minor. It is vital that we memorize all our key signatures as musicians, including both versions of the Enharmonic keys.

How to Quickly Memorize the Circle of Fifths

The best and easiest way to memorize the Circle of Fifths is to remember a phrase, or saying, that really sticks.

A lot of people like to make up their own, and I have heard a lot of great phrases, but in my opinion none beat the original: Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle. The reason why this one is superior is due to the fact that we can say it backwards, as in counter-clockwise, and it still works!: Battle Ends And Down Goes Charles Father.

Rather than making up a different saying for both the sharp and flat keys, we have one master saying that applies to both. Say it over and over again until you have it memorized.

Remember & Repeat: Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle.

How to Read the Circle of Fifths

1. Identifying Sharp Keys

Let's start with the first phrase I mentioned: FCGDAEB.

- We say the phrase in this order to identify which sharp key we are in.

- The first letter of every word is the last sharp of the key.

- From there simply go up a half-step and that note is the name of the major key signature.

Let’s practice this.

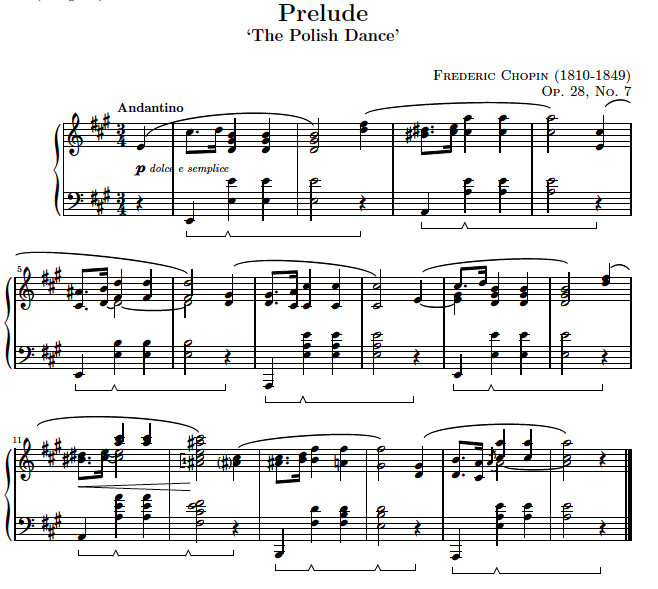

Practice: Here is a prelude by Chopin. Let’s find out what key it’s written in.

The key signature has three sharps. Using our mnemonic: Father Charles Goes, so we have G#. One half step up from G# is A. So the piece is in either A major or F-sharp minor. A quick way to know if it’s the major or minor key is by looking at which note this piece ends on. In the last bar, we see that the bass and the soprano are both A. So it’s safe to say this piece is in A major.

2. Identifying Flat Keys

As mentioned above the second phrase, BEADGCF is the same as the first phrase, but now we are saying it backwards, or counter-clockwise, to identify which flat key we are in.

- When we arrive on the last word, simply go back one word in the phrase.

- Then add a flat to the first letter of that word, thus identifying our key signature!

- This applies to all the flat keys EXCEPT the key of F Major/D Minor, which has one flat, Bb. F Major/D Minor is the only flat key you have to memorize.

- For the rest, go back one word.

Let's apply this technique.

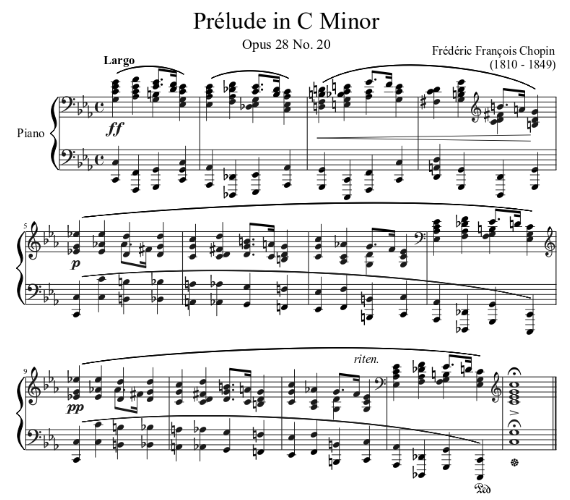

Practice: Let's look at another prelude by Chopin. How many flats do you see resting on the staff?

Yes, there are 3 flats. Using our mnemonic: Battle Ends And, one word back from And is Ends (Eb). So it is Eb Major/C Minor.

If a piece has 5 flats, we use mnemonic: Battle Ends And Down Goes, one word back from Goes is Down (Db); It is Db Major/Bb Minor

If a piece has 1 flat, you'd have to remember that the key of one flat is F Major/D Minor.

Benefits

Knowing the number of sharps or flats in a key will save you a lot of time when studying.

“Five sharps! Oh noo…” This is a common feeling for a lot of musicians, but don’t think that way! Instead say, “oh, five sharps, that’s …… B major/G# Minor!”

Now that we know what key we are in, we can practice the scale and arpeggio a few times and embrace the five sharps rather than being intimidated. This helps strengthen our relationship with the key and it will make reading in that key much smoother.

How Do I Know if the Piece is in Major or Minor?

Remember: To identify if a piece is major or minor, go to the last measure in the piece, and identify the last chord in that measure. Ninety-nine percent of the time, this is the key our key signature indicates.

Practice: Open a piece of music, look at the key signature and compare it with the last chord

- No sharps or flats, last chord is A C E: piece is in A Minor

- 1#, last chord is E, G, B: piece is in E Minor

- 5bs, last chord is Bb, Db, F: piece is in Bb Minor

- 7#s, last chord is C#, E#, G#: piece is in C# Major

Tip: If you are not sure how to identify the last chord, start by looking at the lowest note. This will be in the bass, and that note is the root of the chord. With that knowledge play the chord and try to hear if it is major or minor.

Tip: If you are still unsure, feel free to look up the key of the piece. After you have discovered the key, go back and listen again to the quality of the chord to help your aural recognition.

Picardy Thirds

However, some pieces in minor will end with a Picardy Third, which means that the minor third of the chord is raised a half-step to make the chord major.

This is more common in 17th century music and choral music. Nevertheless, whenever a Picardy Third is used to make a minor key end on a major chord, the bottom note of that chord is the same as it would be for the expected minor chord.

Example: If we are in A minor, a Key signature with no sharps or flats, we expect the last chord to be minor, A C E. However when we get to the the last chord in the piece we encounter an A C# E Major Chord. This is a Picardy Third, which raised the minor third in the chord to major.

Applying The Circle Of Fifths Theoretically

For those who do not know the fourth and fifth scale degrees in a major or minor key, Circle of Fifths offers a quick way to identify chords and the relationship between them. Once you have identified these two notes we can create major/minor triads, and then use them in common chord progressions.

1. Chord Progression I - V - I

The V chord, also known as the dominant is the strongest chord in a key, besides the tonic.

Whenever we play a dominant chord we feel this inner harmonic resistance that must be resolved.

For the most part, the V chord will go to the I chord.

Now some composers like to play with emotions. They will take the dominant on an unexpected journey by resolving to a chord that doesn’t feel quite like home yet. (This is also known as a deceptive cadence.)

2. Chord Progression I - IV - I

This progression is very popular, especially among pop music. Prior to the 19th century the IV-I progression was used primarily in the Catholic and Christian Church. Whenever we sing “Amen” we sing IV-I. “Ahhhh” is the IV, and “Meeeen” is the I.

Luckily to find the V and IV with the Circle of Fifths, all we have to do is find the key that we are in and look at the two neighbor notes. If we are in C major, the top of the circle, to the left we see F(IV), and to the right we see G(V). This holds true for all the keys.

3. Chord Progression I - IV - V - I

The IV chord, also known as the subdominant, was used primarily as a bridge to smoothly navigate to the dominant V chord, which then leads back to the tonic I chord, IV-V-I, for almost two centuries. This period in music history is known as the Common Practice Period. In recent decades, this progression is also commonly heard in pop songs and various styles of music.

Luckily to find the V and IV with the Circle of Fifths, all we have to do is find the key that we are in and look at the two neighbor notes. If we are in C major, the top of the circle, to the left we see F(IV), and to the right we see G(V). This holds true for all the keys.

That “Baroque Sound?”

A lot of composers in the 17th century were inspired by the circle, and implemented a chord progression moving down by fifths, or up by fourths, in their music. Today, a lot of people describe this as the “Baroque Sound.”

This sound is easy to recreate and can open up a lot of possibilities.

Start on the tonic of the key, and then create your chord progression going down by fifths, or up by fourths.

Remember: For the Baroque sound, the secret is to play the chords in the same key signature--use the same number of flats or sharps, don’t add or subtract from the key signature. Ex: C Major: C(I) - F(IV) - Bdim(viio) - Emin(iii) - Amin(vi) - Dmin(ii) - G(V) - C(I)

Each of these chords is a fifth away when going down, or a fourth away when going up. Whether you go up or down is entirely up to you. The “Baroque Sound” is often a fourth up, fifth down.

This ideology has been used in compositions in every century and is still used to this day.

Armin Van Buuren also uses this, but with a little twist at the end by going for the V suspension to the Major I chord in second inversion. It begins at 2:01-2:08, then repeats.

In Conclusion

Regardless of your path in the musical arts, learning the Circle of Fifths can open a lot of doors for both knowledge and creativity. With it, you can identify any key signature regardless of the number of sharp or flats, have quick access to the identity the IV and V chords in any key, and teach you that “Baroque Sound.” Keep coming back to our blog for more helpful musical tools and lessons about complicated topics and browse archives!

Ready to learn music?

Start learning with our 30-day free trial! Try our music courses!

About Liberty Park Music

LPM is an online music school. We teach a variety of instruments and styles, including classical and jazz guitar, piano, drums, and music theory. We offer high-quality music lessons designed by accredited teachers from around the world. Our growing database of over 350 lessons come with many features—self-assessments, live chats, quizzes etc. Learn music with LPM, anytime, anywhere!

Wonderful and useful web-site! Thanks a lot! Thanks once again!

Thank you for the feedback. I appreciate all feedback.

A very good explanation of the Circle of fifth!!! Thanks

Thank you for explaining compositional uses of this, especially the Baroque Sound!

I’ve always found the circle of fifths useful for visualizing Modes:

If you take the set of 7 notes used in a scale/mode/key, e.g. clockwise F-B (F-B=no sharps or flats), you get a semicircle on the circle of 5ths. The tonic notes of the modes are ordered in the semicircle from “brightest” mode (Lydian, F) on the left to “darkest” mode (Locrian, B) on the right.

Conversely, you can choose a mode you’d like to move to (e.g. modulate from Bb major to Bb Dorian) and re-position the semicircle to find the notes used (the Dorian tonic note is in the ‘middle’ of the semicircle so 4 flats are used, Db-G clockwise on the circle)