In this article, I will talk about the origins, functions and structure of music in Sonata form. I will also dive into our musical analysis of Haydn's renowned composition.

If you have performed a piece of music by either Haydn, Mozart, or Beethoven, then you have probably encountered a work in sonata form. Most first movements1 of the symphonies and concertos, as well as the chamber and solo instrumental works, by these composers are organized into sonata form. Typically, the tempo of these opening movements is fast, which is why it is sometimes referred to as sonata-allegro form.

This type of structure was common during the late 18th century, but we only know it as “sonata form” from the writings of the music theorists of the following century. No composer or theorist used the exact (translated) words, “sonata form,” until the German critic Adolf Bernhard Marx (1795–1866) introduced the concept during the mid 19th century in his Die Lehre von der musikalischen Komposition, praktisch-theoretisch (1845). Marx focused primarily on Beethoven’s sonatas and concludes that sonata form basically consists of three distinct parts—what we refer to now as exposition, development, and recapitulation. Although Marx was the first to coin the concept of sonata form, other musicians and theorists alive during the lifetimes of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven—such as Francesco Galeazzi (1758–1819) and Anton Reicha (1770–1836)—describe the form in their own way.

Historical Background

[Joseph Haydn] [W.A. Mozart] [Ludwig van Beethoven]

The sonata forms of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven were composed during a period of social-political change (e.g., the downfall of monarchies and the birth of democracy) and stylistic changes in music. Musicologist Charles Rosen identifies two radical periods of stylistic change in which a simplification process unfolded during the mid- and late-18th century. The first massive change (1730–1765) reduced the complexity of textures while the second transformation (1765–1795) served several purposes: the growth of amateur musicians among the middle and upper classes needed less complex music to perform; the growth of public concerts demanded “easily comprehended” and “dramatically conceived” music; there was a growing taste for the simple and natural instead of complex; and a new focus inward to personal expression of feelings and emotions (Rosen, 13).

Consequently, when writing works for public consumption, composers gained a certain degree of expressive freedom. As Richard Taruskin points out, the symphonies of C. P. E. Bach (1714–1788), exceptionally “stern and stormy, harmonically restless and unpredictable,” were more difficult and not for “the average partygoer”; in contrast, his younger half-brother, J. C. Bach (1735–1782) wrote “high-class party music” (Taruskin, 508). Although the 19th -century historians—especially E. T. A. Hoffmann—in favor of the works of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven overlooked much of the works of the Bach sons, by the time the latter three were writing symphonies and instrumental chamber works, their sonata forms had grown to become as dramatic and expressive as the operas of the same period.

The structure and function of sonata form

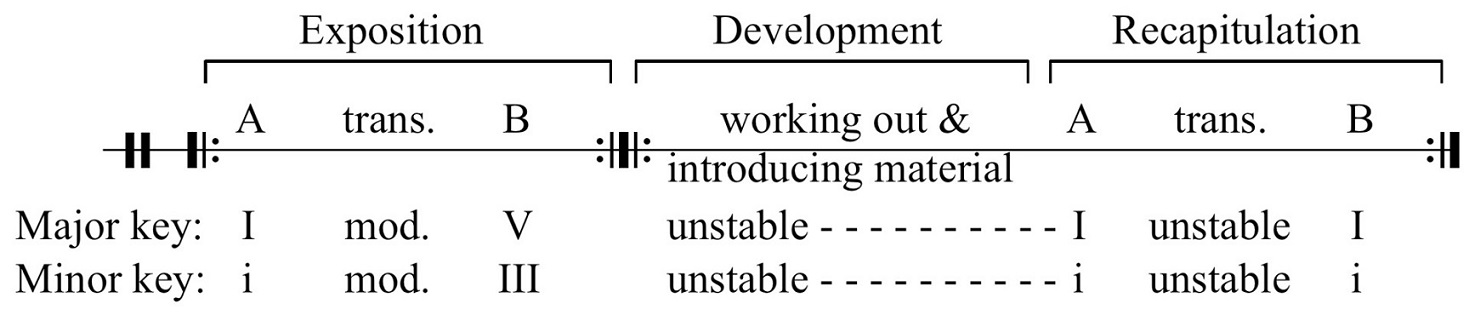

Sonata form mixes binary2 and ternary3 form. Harmonically, a sonata form movement in sonata form has two halves: the exposition is the first half, and the development and recapitulation are the second half. In terms of thematic development, it has three main sections: exposition, development, and recapitulation.

(Image from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sonata_form#/media/File:Sonata_form_two-reprise_continuous_ternary_form.png)

Exposition:

The first section, exposition, often has two themes: primary theme in tonic and second theme, often in dominant for major pieces or relative major for minor pieces. A transition section often functions as the harmonic catalyst to prepare the new key in the second theme, but not always. Following the perfect-authentic cadence (V-I cadence with both chords in the root position and tonic in the highest voice of the last chord), which functions as a confirmation of the new key.

Development:

The development is the most unstable section; anything can happen here. It usually begins in the new key only to quickly depart on an exploration of other key areas before returning to a dependent dominant that creates a strong expectation for a double-return recapitulation in the opening key. Composers might use a variety of tricks to reuse thematic materials previously used: fragmentation, sequence, variation, etc. Occasionally, a development section features a “false” recapitulation—one that sounds like a melodic restatement of the opening theme, but, upon examining the music (or if you have perfect pitch), the key is not the same as the beginning of the exposition.

Recapitulation:

The recapitulation section is the “homecoming” section; after all the adventures, the characters return home with slightly different outlooks. The section often opens with the primary theme in tonic key, termed “simultaneous return”: the return of key and theme. The “sonata principle” also applies, meaning the second theme is in tonic this time. In other words, both themes are in the tonic key, in which the form begins, to close the entire sonata form.

In short,

A large-scale harmonic tension-resolution schema begins with harmonic instability in the transition section of the exposition, which is amplified and put on display in the development and finally resolved during the second theme’s perfect-authentic cadence in the recapitulation. The movement can open with an optional introduction and an optional coda4, but we won’t get into these in this article.

The function of sonata form: dramatic and harmonic

A sonata-form movement is dramatic because it contains at least two contrasting themes. Listeners follow the two themes, primary and secondary (or main and subordinate), through their introductory statements in the exposition section, their transformations in the development section, and their restatement in the recapitulation. On the one hand, the three large structural areas of a sonata form typically contain elements of thematic contrast, which elucidates a simpler narrative than the complex contrapuntal5 techniques of the Baroque period.

On the other hand, however, sonata forms also contain a harmonic narrative of tension–resolution. Harmonically, the goal of the exposition section is to move away from the “home” (tonic) key, which is typically the key of the dominant (V) in major keys and the key of the mediant (III)—which is also the relative major—in minor keys. The exposition, just as it contains more than a single melodic theme, thus contains more than one key area.

So this is all you need to know about sonata form’s history, structure, and function. If you would like to see how it works in music, continue reading.

The function of sonata form: dramatic and harmonic

A sonata-form movement is dramatic because it contains at least two contrasting themes. Listeners follow the two themes, primary and secondary (or main and subordinate), through their introductory statements in the exposition section, their transformations in the development section, and their restatement in the recapitulation. On the one hand, the three large structural areas of a sonata form typically contain elements of thematic contrast, which elucidates a simpler narrative than the complex contrapuntal5 techniques of the Baroque period.

On the other hand, however, sonata forms also contain a harmonic narrative of tension–resolution. Harmonically, the goal of the exposition section is to move away from the “home” (tonic) key, which is typically the key of the dominant (V) in major keys and the key of the mediant (III)—which is also the relative major—in minor keys. The exposition, just as it contains more than a single melodic theme, thus contains more than one key area.

So this is all you need to know about sonata form’s history, structure, and function. If you would like to see how it works in music, continue reading.

Musical Example: Haydn’s keyboard sonata in G major (Hob. XVI: 27)

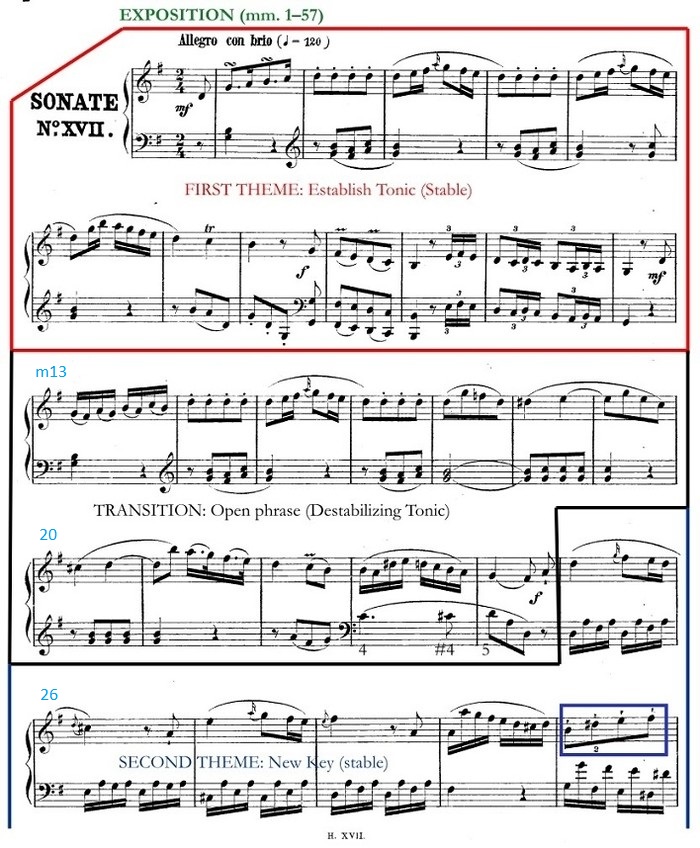

The first movement contains all three major sections of the sonata and provides an excellent major-mode example of the procedure outlined above.

In the exposition, the first theme (mm. 1–12), enclosed in a red box, is a harmonic progression in G major that remains harmonically stable because it does not modulate6. The transition (mm. 13–24), highlighted with a black square, also fundamentally remains in G major, but ends with a half cadence instead of an authentic cadence. In other words, the phrase is left open on the dominant harmony (D major)—we expect another phrase in G major to close this section on the tonic—and thus initiates harmonic instability.

Melodically, however, you will also notice Haydn’s introduction of the C# in m. 20 (top staff) and in m. 23 (bottom staff). The former is part of a sequence and the latter is part of a chromatic intensification (scale degrees 4–#4–5) of the half cadence at m. 24. The C#s belong to the key of D-major, the dominant key (V), the key in which Haydn begins the second theme (mm. 25–55).

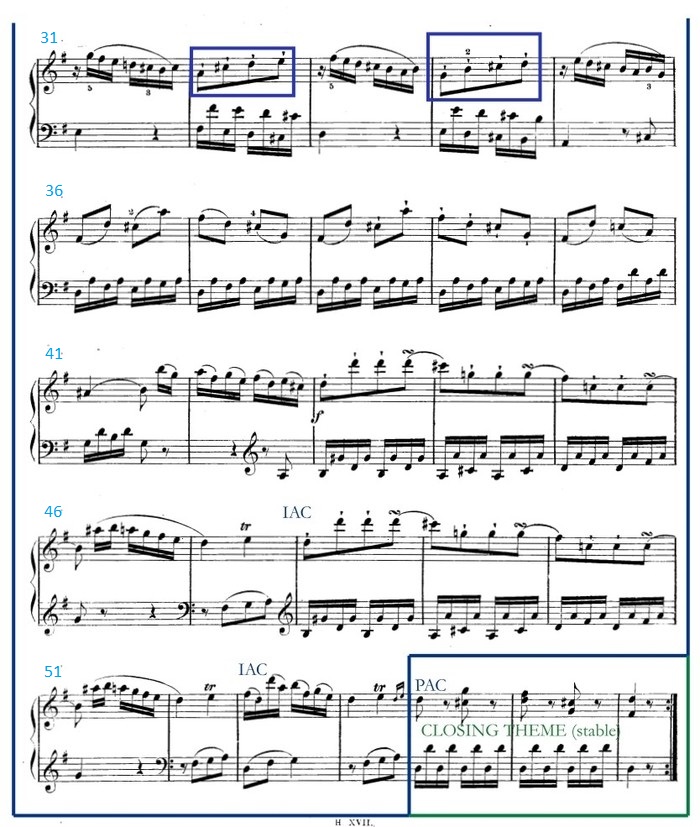

Except for a few brief harmonic departures, the second theme, in dark blue, ends firmly in D major with a perfect-authentic cadence at mm. 55. Haydn could have ended this theme at either m. 48 or m. 53, but he chose to delay the perfect-authentic cadence until m. 55 by using the imperfect-authentic cadences at those two points and restating mm. 43–47 during mm. 48–52—as if Haydn exclaimed, “let’s hear that one more time!” (a trick also common in Mozart’s expositions).

The short closing theme (mm. 55–57), in green on the score, sustains the D-major goal and functions as extra confirmation of the new key. (For more on the “one more time” trick, see the work of Janet Schmalfeldt—especially her book, In the Process of Becoming.)

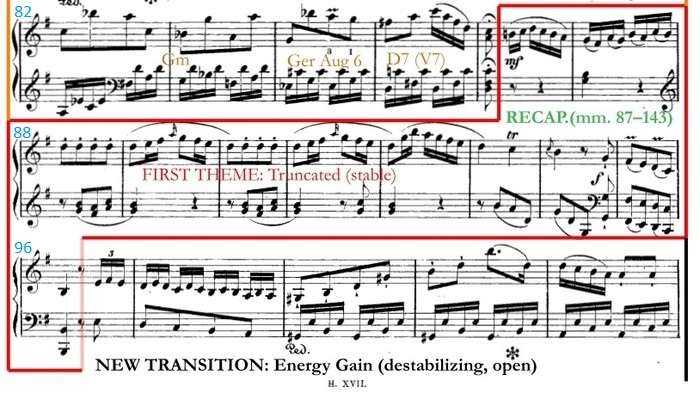

Encapsulated by orange borders on the score, the development section (mm. 58–86) takes motives from the second theme as its melodic subject (see the staccato eighth-notes in the top staff). By doing this, Haydn incorporates previous thematic material into the development.

However, the development’s harmonic path is completely unstable beginning with the abrupt move to the minor dominant in the first measure. The next harmonic event features a prolonged rising circle-of-fifths harmonic progression (D–A–E) moves the key to the submediant minor for a period of brief stability (mm. 65–73). A quicker-moving falling-fifths progression with seventh chords follows (mm. 73–77) and actually returns to the home key (G-major) for a moment before it too transforms into its minor-mode counterpart (mm. 79–85). The fermata on the dominant seventh in m. 86 is a huge signal of an impending return of familiar sounds—the period of harmonic flux is coming to rest and the storm may be over.

While the recapitulation (mm. 87–143) does correspond with the exposition’s phrase and thematic structure, you will notice a few deviations. For example, the first theme is shortened because its final sub-phrase dissolves into the a novel transition section that was not present in the exposition (compare mm. 13–24 with 97–106).

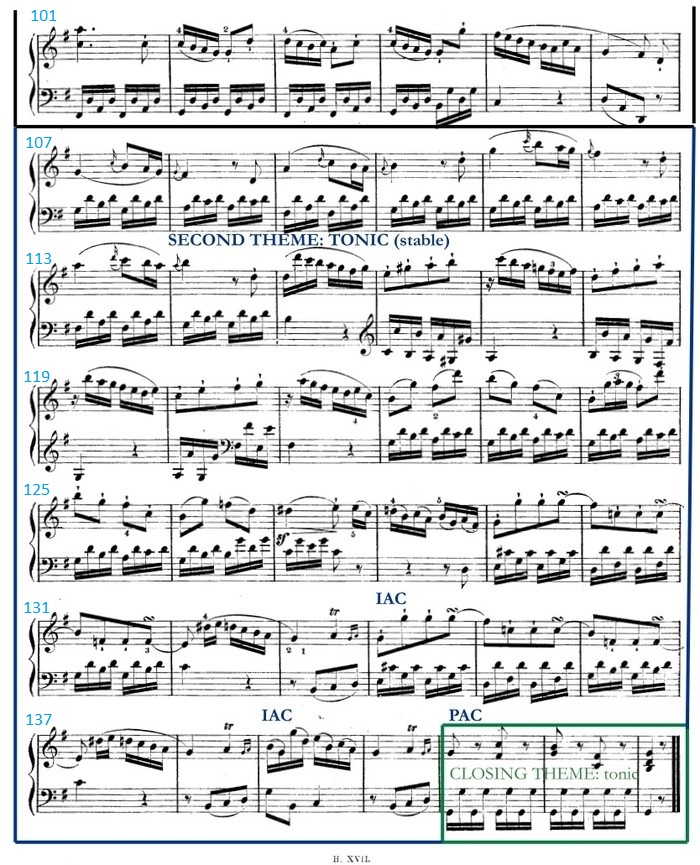

Remember, In the recapitulation, the transition typically does not modulate from the tonic key. Haydn plays against this expectation by influencing the transition with references to the lively motives and harmonic sequences of the development. It also functions as a clear energy-building and exciting contrast to the first theme. At m. 106, though, Haydn ends the transition with the same half cadence as m. 24, which marks a clear indication that the second theme could start in G-major.

At the onset of the second theme in m. 107, it is clear upon comparison that Haydn intends to end the movement in G major. With the exception of the transposition7 down a perfect fifth (to comply with the key of G major) plus four added measures (mm. 111–114), the second theme corresponds measure-by-measure with its earlier statement in the exposition. Haydn even reuses the “one more time” technique of the exposition’s second theme in the recapitulation with imperfect cadences at mm. 134 and 139. Following the perfect-authentic cadence at m. 141, the G-major closing theme (mm. 141–143) echoes its dominant-counterpart in the exposition and the movement is effectively closed.

This article introduces the history and specifics of sonata form as well as how it works in music, when you go to a concert that includes a movement in sonata form, you can try to spot the themes and the different sections and hear what the composer is trying to communicate!

Glossary

1. Movement: An individual section that is part of a complete composition which comprises other movements as well

2. Binary form: Consists of 2 related sections, A-B

3. Ternary form: Consists of 3 sections, usually structured as A-B-A

4. Coda: A designated passage that brings a musical composition to the end.

5. Contrapuntal: Related to counterpoint, consists of 2 melodic lines playing simultaneously.

6. Modulation: A change from one key to another

7. Transposition: Moving a musical passage to a different pitch, by a consistent interval

References

Charles Rosen, Sonata Forms (New York: W. W. Norton, 1980).

Richard Taruskin, Music in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (Oxford University Press, 2009).

Ready to learn music theory?

Start learning with our 30-day free trial! Try our music theory courses!

About Liberty Park Music

LPM is an online music school. We teach a variety of instruments and styles, including classical and jazz guitar, piano, drums, and music theory. We offer high-quality music lessons designed by accredited teachers from around the world. Our growing database of over 350 lessons come with many features—self-assessments, live chats, quizzes etc. Learn music with LPM, anytime, anywhere!

Great help, thanks! What’s IAC? You putted it at 48, 53 and in other measures.

IAC= imperfect authentic cadence. An “authentic cadence” is a cadence ending with a V-I progression. A “perfect authentic cadence”, or “PAC”, would have both chords in root position: the roots of both chords are in the bass, and the tonic (the same pitch as root of the final chord) is in the highest voice of the final chord. An IAC is an AC that is not a PAC. A common example of an IAC is that one of the two chords (either V or I) is inverted, or the ending I chord does not have the tonic in the highest voice. Let me know if this clarifies. 🙂