Introduction

Have you ever watched a great pianist perform a complicated piece from memory? Impressive, isn’t it? All those notes and details, perfectly remembered and then fantastically re-created in the moment. There’s something about a performance of memorized music that makes it feel somehow more authentic, more intimate and honest. To be sure, this is a subjective perception, as many of the greatest performers used sheet music when playing, but the appeal of a memorized performance certainly exists.

The practice of memorizing music is different from the more standard modes of practice to learn music off the page. In some ways memorizing music may seem easier, as our minds form a kind of magnetic attachment to repeated material. Indeed, you’ve probably found yourself inadvertently memorizing parts of your pieces simply from playing them again and again. But there is a difference between this inadvertent memorization and the kind that results in glorious, sheet-music free concerto performances by ecstatic looking piano superstars. Intentional memorization is methodical, detailed, and driven towards internalizing as much of the music as possible. The ease and musical connectivity you witness in those great performers comes from an utter confidence of knowledge; they know the music inside out, upside down, and backwards, and they’ve left no wiggle room for uncertainty. This kind of memorization is a practice unto itself, and it’s a valuable pursuit that every pianist should try at least some of the time.

Fortunately, while the results of concentrated memorization practice can soar to great heights of performance acumen, the work itself is grounded in accessible strategies.

Let’s take a look at some strategies to practice memorizing music.

Repetition, Repetition, Repetition…

As we’ll see, there are a number of ways to complement your efforts at memorizing music, but at its core memorization revolves around one activity: repetition.

No matter how good their strategies of memorization, most musicians will have to repeat their chosen material many times before it can be truly memorized. This is not dissimilar to using repetition to learn music while practicing, but in this case we’re talking specifically about repetition with the intent to memorize.

The reason repetition forms the foundation of memorization practice comes back to the physiological objective of memorizing; we want to have the music in the “muscle memory” of our hands, and the most basic action we can take to achieve this goal is to repeat the material until we’ve sufficiently minimized the mental effort it requires to think about the music consciously. Thinking about whether the notes you’re playing are the right ones or are being played the right way is a train of thought that belongs in the practice room, not on the performance stage. We want the music deeply settled within the boundaries of our understanding, and constant, confident repetition of the material is the simplest way to make this happen.

Many experienced musicians, regardless of style or genre, will employ some form of memorization strategy when learning music, but no matter how effective the memorization strategy, repetition is an essential part of the equation. Many methods of classical pianism continue to emphasize sheer repetition in the development of musical memorization, which works fine if you have four to eight hours a day for practicing. But if the time you can dedicate to musical efforts is limited, coupling your memorization practice with the methods detailed below will help you to memorize more quickly and thoroughly.

Slow down and Break Down

Perhaps the most basic memorization strategy borrows tactics from the general strategies of slowing down and breaking down during regular practice. The logic behind this strategy is simple: information is tends to be easier to assimilate when it’s coming more slowly, and in smaller, less complicated chunks.

Slowing down as a process may seem self-explanatory; you slow down your execution of the music so that your brain can more easily absorb the material and log it to memory. However, there are a few recommendations to be made concerning how you go about it, such as using a metronome to lock yourself into a particular speed and adhering to a steady beat (with which the metronome can also be of help). We explain these methods in detail in our (6 Strategies Missed by Pianists) article, so be sure to check out that article here. Slowing down should be a de facto filter through which you solidify any practicing strategy.

We find a more diverse array of options in the breaking down process, such as identifying and applying technical or theoretical labels, picking out specific phrases or visual structures, and even drawing attention to parts of the music through highlighting or other non-musical aids.

Breaking Down: Know Your Theory and How it Applies

The term “music theory” may elicit winces and grimaces from those who dread to tread its occasionally convoluted pathways; however, most musicians encounter music theory throughout the course of their day-to-day practicing. Scales, chords, intervals, arpeggios…these all fall under the umbrella term “music theory,” and you don’t have to know a thing about the more elaborate forms of theory to help with memorization.

Using the elements of music theory to bolster your memorization practice is actually a double-edged strategy. On the one hand, you’re breaking down the music into more manageable pieces, but you’re also recasting the more minute details of notation into bigger structures. For example, picking a recognizable scale out of a longer passage not only serves to helpfully break down the passage, but also compiles all of the smaller notes of the scale into a single, larger entity with a clear function.

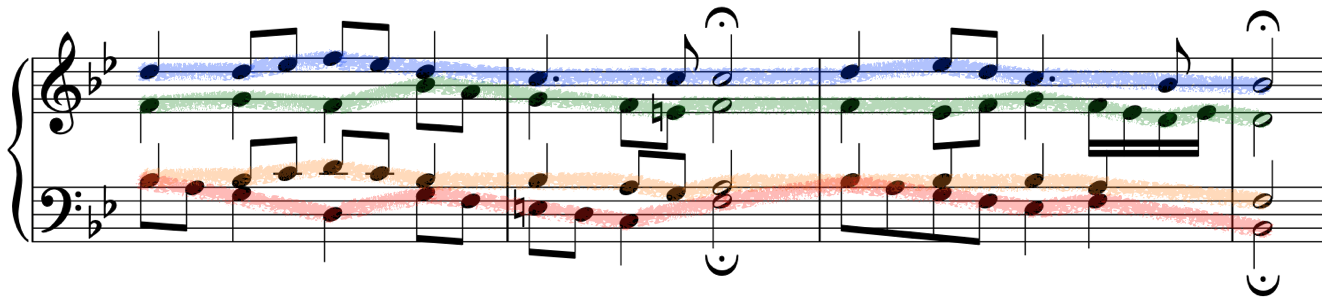

Let’s take a look at some music to see how this kind of theory identification works:

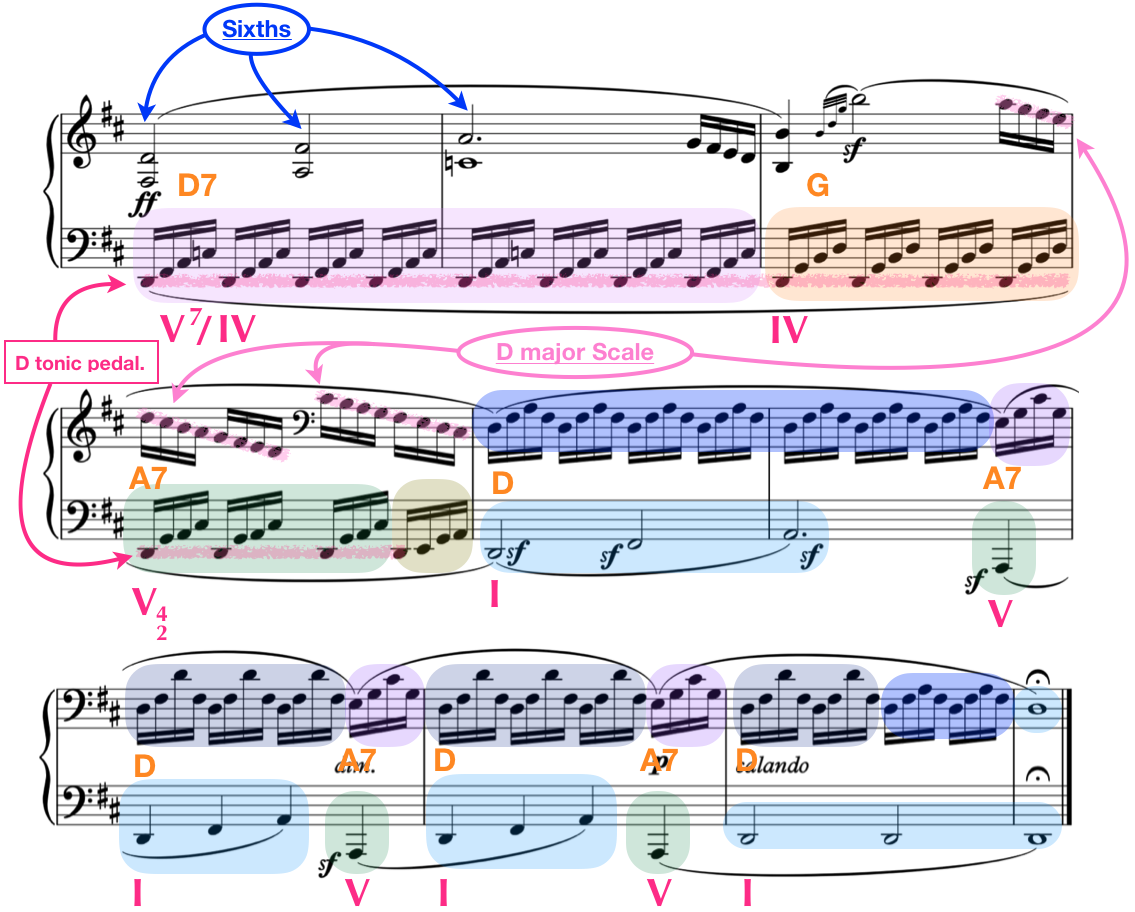

This busy looking passage of music is from the final measures of the first movement of Muzio Clementi’s Sonata in D Minor and Major, Op. 40, No. 3. This passage is a good example of music that looks impressive and daunting to less experienced pianists, but that more experienced pianists (particularly those with a deeper knowledge of theory) are unintimidated by due to the relative simplicity of its theoretical material.

Let’s see how this passage might look through the eyes of a pianist using theory to break down its structural properties:

Notice that we have several kinds of theoretical identification happening. On a more basic level we can see the continuous lines of 16th notes broken down into chords and scales, represented here via different colors. On a more advanced level we can see the roman numeral analysis indicating the direction of tonal movement (in magenta), pointing to the inevitable final cadence. The pianist adept in breaking down the music will see most of these things at a glance, and require significantly less time to memorize this passage.

A pianist’s ability to break down and assimilate this passage using theoretical tools is an excellent example of the value of applied music theory. The more theoretical tools you can incorporate into your memorization practice, the more effectively you’ll be able to break down complex passages into memorizable pieces.

Breaking Down: Melodies

Melodies are some of the easiest elements of music to memorize, and the evidence for this is everywhere. How many times have you walked through the grocery store or the mall only to come out with the melody to some pop song you’ve never heard before aggravatingly (or pleasingly) stuck in your head? In fact, our brains find it so easy to memorize melodies that you can probably think of (or even sing) far more melodies off the top of your head than you can play on your instrument!

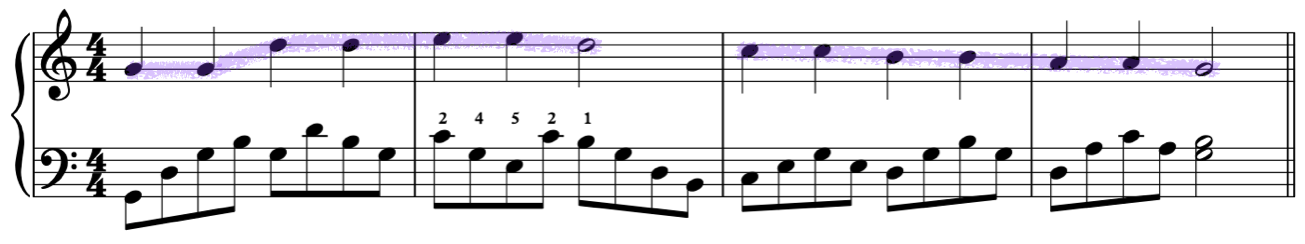

To repurpose some of that ease to our advantage when trying to memorize things at the piano, the first thing to understand is that melodies can be found in a wide variety of guises, particularly within piano literature. As a beginning or intermediate pianist, the most common kind of melody you’ll encounter is the prime melody, or the part of the music that would typically be sung be a vocalist:

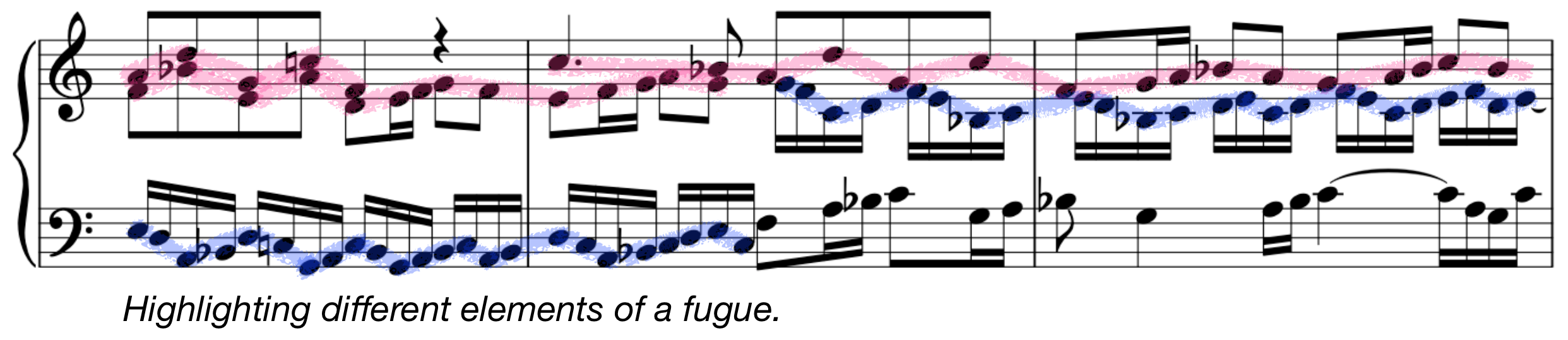

At some point you’ll probably encounter music that is built using the interweaving of multiple melodies (known generally as polyphony, or more specifically as counterpoint):

Once you learn to see melodies in different ways throughout your music, you’ll be able to pick them out even within dense musical textures. The ability to translate a broad spectrum of musical material into a melodic language will greatly enhance the efficacy of your memorization.

Beyond simply recognizing melodies, we derive form-based memorization from melodic phrases, which often have clear beginning and end points. To better envision how this works, conjure the melody to Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star in your head. Now imagine it or sing it only up to the word “what,” and then stop: “Twinkle, twinkle, little star, how I wonder what–”

Weird, right? The strangeness you’re encountering is not entirely due to how ingrained the melody is in your memory; this kind of cut off would probably sound strange in most circumstances. Having a sense of the balance of melodic phrases is a key component of melodic memorization.

Finally, don’t be afraid to sing the melodies you want to memorize in your piano music. You don’t need to sing them perfectly, but attaching the seamless bridge between your brain and your voice to the more distant functions of your fingers is often helpful when memorizing.

Non-musical Aids: Colors, Numbers, and Words

Assuming you’re reading this past the age of childhood, your mind is most likely equipped with a wide array of associative tools that you can use to piece together unfamiliar material. Colors, numbers, and words can all be used in conjunction with your logic and associative reasoning to imbue seemingly random information with recognizable value. Whether or not you believe music notation is akin in character to a language, it is at best a second language for most people and therefore requires aid from our other rational capabilities to subsume into a natural (and easily memorizable) understanding.

All of which is an elaborate way of saying: Draw on your music!

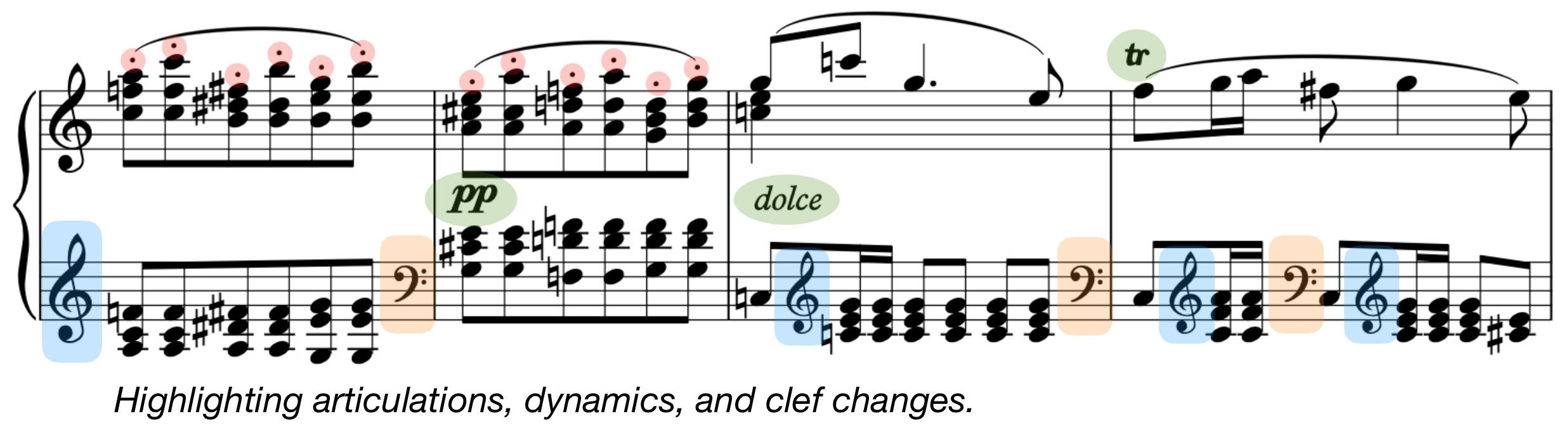

Well, don’t necessarily draw on your music, but do take advantage of being able to color or otherwise mark up your scores to aid with memorizing.

In our wonderful world of black and white manuscripts, colors can be useful for illuminating important musical components. Highlighters, colored pencils, even colored pens (preferably erasable ones) can be used to draw attention to everything from small details to large formal structures. With regards to memorization, coloration can helpfully push aspects of the music to the forefront of your scrutiny, which lets you internalize (and therefore memorize) them more easily.

We’ve already seen a few examples of highlighting in the previous sections, but let’s look a few more:

Words are another non-musical aid you can use to help with memorization.

Going through your music and writing out descriptions of sections, figures, or phrases is a good way to involve the more developed areas off your knowledge in the process of musical perception. For example, describing the movement of a passage in words (instead of leaving a relatively blank mind to absently play through the notes without any qualifying concentration) can help you think about that movement in a more familiar light, which will make it easier to memorize.

A second, somewhat more creative way to use words to your advantage when memorizing is to assign lyrics to melodic content that doesn’t have any. This can be especially helpful with rhythms.

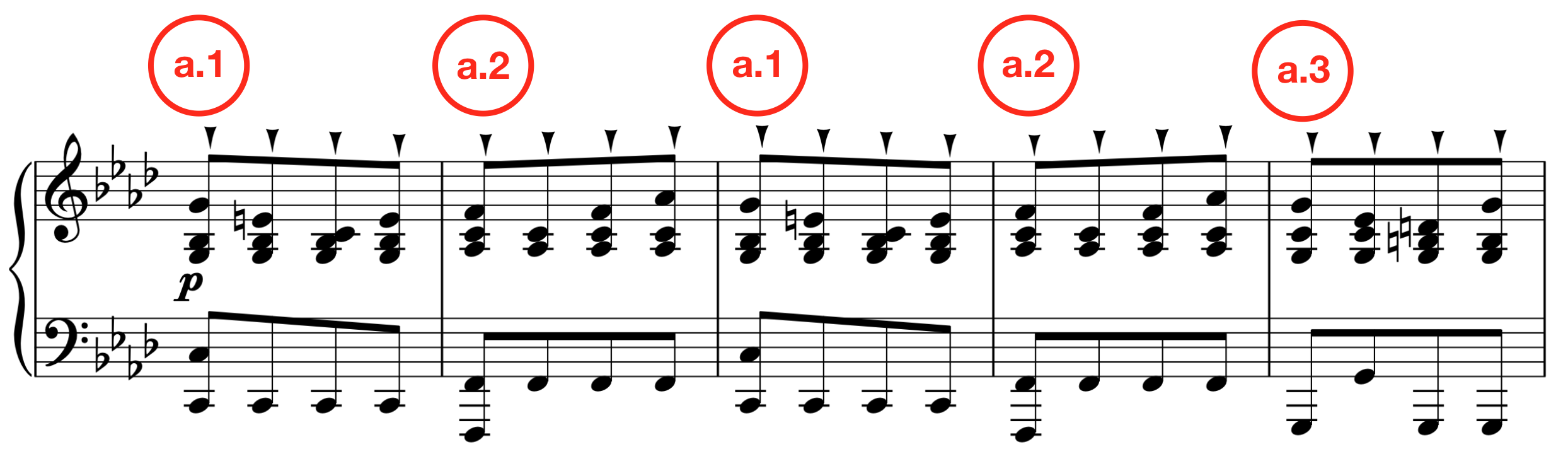

Finally, you can use numbers to organize and categorize parts of your music. The Western notation system of using measures and rehearsal letters is a built-in way to help performers keep track of the music, but you can take it a step further by numbering figures and phrases and then associating those numbers with their relevant content. This can be helpful when you try to memorize numerous, similar sounding figures that have slight differences:

Additional Tips

Here are some additional tips for you to consider when memorizing:

- Memorize often: The more you exercise your memorization muscle, the stronger it will become, and the more efficient you can get the notes through your brain and into your muscle memory.

- Avoid memorizing too much at once (at least until you’ve gained some experience with memorization). Memorizing tends to work better when done in smaller chunks over a number of practice sessions. You can increase this amount with practice experience, but if you’re just starting off, less is more.

- Different styles of music can require different methods of memorization, and stepping outside the boundaries of your normal style to engage some of these alternate methods can bolster your skills in your home style. For example, if you’re primarily a classical pianist but you know a bit about chords and improvisation, you might try memorizing a jazz or pop chart, which requires you to think less about specific notes and more about note ranges, chord voicing options, and stylistically appropriate accompaniment.

- Don’t forget that a little strategic listening can be a big help when trying to memorize. Listening to recordings of the music you’re working on will certainly get the sound of the music into your head, which helps with memorizing. Be careful though: not everyone appreciates the same kind of interpretation, so if you’ve been getting the sound of a particularly idiosyncratic interpreter’s rendition into your ears, be prepared to field some questions!

- If you know you’ll be performing a piece from memory that you haven’t played in a while, feel free to go back and do a read through with the score. Make sure you practice more slowly than you might normally, and be ready to close the sheet music again once you’re confident that your memory banks have been sufficiently dusted off.

Conclusion

Being able to perform with sheet music is great, but nothing says that you own a piece quite like being able to play it from memory. The process of memorization can be daunting if you don’t know how to get started, so we hope that the tips for memorizing in this article have given you some confidence.

For more on practice strategies, as well as all things piano, stay tuned to Liberty Park Music!