Introduction

Why do we practice music? Your answer may be something to the effect of, “well, we practice so that we can play the music,” which is pretty much correct, but can be stated a little more succinctly: whether you’re planning to play in front of a blowout crowd at Carnegie Hall, a modest gathering of friends and family at a holiday gathering, or simply for yourself in the privacy of your own home, the goal is the same, we practice to perform.

Ok, but what exactly is practicing? Or, more importantly, how do we practice? What are we supposed to do when we practice?

You’ve probably acquired some practicing habits through your studies thus far, but how would you explain your practicing process if asked?

As a piano teacher, I ask this of my students fairly often, and all too often I get some pretty indistinct answers. Many of these answers involve starting at the first note and ending at the double bar, with whatever happens in between left up to good fortune and dogged determination. While this may seem intuitive, it describes what is probably the least efficient version of practicing, and students who do little to expand the breadth of their practicing strategies often fall prey to a range of similar issues.

In this article we’re going to explore six of the practice strategies commonly overlooked by pianists. This list is loosely prioritized from front to back, with the strategies at the end being more consistently valuable to the practicing process, but any of these can take priority depending on your specific practice needs. As an added caveat, this list is not meant to represent all of the important strategies a practicing pianist might neglect. Your teacher, or another experienced musician, may be able to help you further if the strategies herein don’t seem to help.

So, without further delay, let’s get started.

Listening

You may be thinking to yourself, “Really? Listening? What does listening have to do with practicing?”

When was the last time you listened to a piece of solo piano music? More to the point, when was the last time you listened to a piece of solo piano music that was not a piece you were working on? For some the answer will be, “quite recently,” but for many listening misses the priorities list, which is a shame because it really is an essential part of improving our musicianship.

Nearly all of the best musicians you’ve ever heard have one thing in common: musical saturation. They eat, drink, and breath music. Their lives (and ears) are constantly saturated by the sounds of their art, such that even when they’re not practicing, the melodies, harmonies, and rhythms of their music are perpetually swirling around inside their heads. This is part of the reason why performance majors in colleges and conservatories are pushed to seek out as many performance opportunities as possible; there are few better ways to absorb the sounds and performance practices of music than to be absorbed by them.

For musicians not in a collegiate setting, daily listening can be the best way to create a musically saturated environment. This is a different kind of listening than concentrated listening, where you sit and listen to a piece you’re working on to get it in your ears (though that too should be a part of your initial musical research). Here we’re referring more to the practice of general daily listening, in which you try to engage in music-listening whenever you can throughout your day. This is listening as much for your subconscious mind as for your conscious one, and you may find that the benefits of it appear unbidden as you work on your music.

Here are some tips you can use to help you get the most out of your listening.

First, don’t be afraid to put on music in the background of your daily activities, even if you can’t spare the brainpower to listen to it directly. Cleaning the house? Put on some music. Taking the train to work? Put on some music. Cooking dinner? Put on some music. While being able to concentrate on the music you’re listening to is important, you can still reap the benefits of getting the sound in your ears through frequent, less formal listening.

Second, try to listen to styles of music that are related to the music that you’re practicing. While you can certainly gain some worthwhile musical insight listening to the Beatles, doing so is probably not going to help you internalize the sound of Chopin. You can also listen to music that is similar in style, but different in genre or theme. Working on a Mozart sonata? Listen to other Mozart sonatas, as well as to his symphonies, operas, and chamber music. You can also benefit from listening to composers from the same period, even those whose styles may not be particularly similar. Practicing some Debussy? Check out some Ravel for music in a relatively similar vein, and some Mahler for something totally different.

Finally, be sure to listen to different recordings of the pieces that you’re working on. The range of interpretative variations of a written piece of music when played by different players can be astounding. In addition, don’t forget that some older works were written for keyboard instruments other than the piano, and that listening to them performed on those instruments can be illuminating. Ever heard Bach played on a harpsichord? It’s a very different experience than listening to Bach on a piano.

In no particular order, here’s a short list of piano works for your listening pleasure. Input one as the radio station on a streaming service like Spotify or Pandora and see what else comes up!

-Bach: Prelude and Fugue in F minor, Well-Tempered Clavier, Bk. II, BWV 881

-Mozart: Fantasia No. 4 in C minor, K. 475

-Beethoven: Sonata No. 30 in E major, Op. 109

-Chopin: Sonata No. 3 in B minor, Op. 58

-Clara Schumann: Drei Romanzen, Op. 21

-Brahms: Intermezzo in A minor, Op. 116, No. 2

-Debussy: Reflets dan L’eau, Images, Bk. I

-Boulanger: Trois morceaux pour piano

-Shostakovich: Prelude and Fugue No. 2 in A minor

-Ligeti: Étude No. 13, L’escalier du diable (The Devil’s Staircase)

Focus on the Details

Here we’re talking about all the piano’s, the forte’s, dots, and the lines; anything that describes what is supposed to be done to a note when it’s played falls under this category.

One of the biggest differences in the performance of music between more and less experienced players is that less experienced players tend to neglect the execution of details, while more experienced players emphasize them. There are two parts to this, recognition and rendition, both of which contribute to making performance more musical.

Recognizing details in the music is when we are able to identify the articulations and dynamics in the music. This can be challenging when the music has a large number of articulations and dynamics to identify, or when it doesn’t. Have you ever had your teacher raise an eyebrow at you because you missed one of the few dynamic markings in the first movement of a Haydn sonata? Indeed, it can be easy to overlook these details if you’re struggling to get the notes under your fingers, which is why detail identification should be a process unto itself when learning a piece of music.

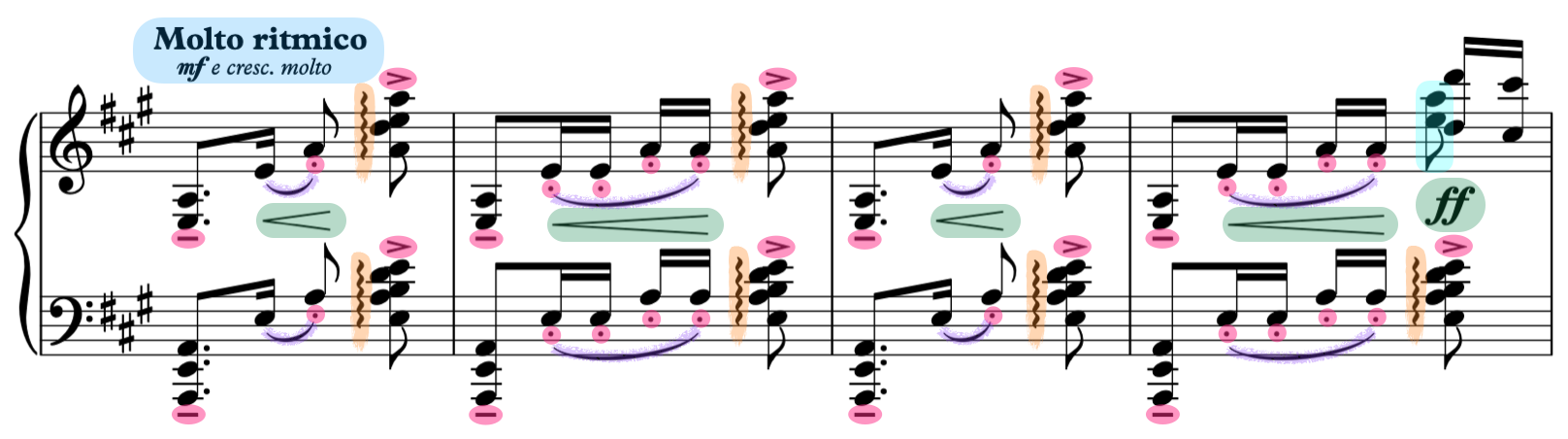

Let’s take a quick look at a snippet from a heavily detailed piece of music:

Looks a little scary, doesn’t it?

This is a section from Debussy’s famed work, La soirée dans Grenade, and in it we can see some good examples of Debussy’s meticulous articulation detail. To be sure, this is a fairly extreme example, but it can be good practice to analyze the details of a busy piece of music to acquire the ability to see things more easily in moderately articulated music.

Before we highlight all of the different details in this passage, see if you can go through and pick them out.

How did you do?

Going through with a highlighter or colored pen and marking all of the details is probably the easiest way to make sure that you’ll be able to see them as you continue working on your music.

The second part of focussing on the details, rendition, has to do with the performance of dynamics and articulations. Have you ever marveled at the way your teacher brings so much life to the music when demonstrating the piece you're practicing? Much of that performance energy comes from realizing articulations and dynamics.

To work on the quality of your rendition, try emphasizing each detail to a greater degree: make your louds louder, your softs softer, your staccatos shorter, and your legatos smoother. Try rendering your piece a caricature of itself by making every dynamic and articulation super extreme, and then dialing back to a more moderate version once you’re confident that you’ve infused your performance with the details.

Listening Link: Debussy: La soirée dans Grenade, L. 100, No. 2

Fingering

Yes, those little numbers above the notes in your music are actually important…

One of the most common handicaps in beginning piano literature (i.e., learning pieces) is the reliance on close hand positions to contain figures and phrases. In other words, beginner pieces tend to avoid more complicated hand movements like crosses, leaps, and wide spans, so that students can become accustomed to depressing the keys that naturally fall under their fingers when they put their hands on the keyboard. This is when we first learn to think of our fingers numerically, and when we first learn that associating the location of our fingers with the relevant hand position helps us play a piece successfully. We spend a lot of time going back and forth between thinking about the note names and thinking about our finger numbers, until we can think of them both more seamlessly.

Once we advance towards the intermediate stage of our skills and have some experience with reading notation, our instinct when beginning a new piece of music is to sightread through it as best as we can to get a sense of its sound and form. This is natural and worthwhile, but the problem is that many pianists never move past this stage to the more studious method of identifying and adhering to a certain fingering, so it can be effectively choreographed into the hands.

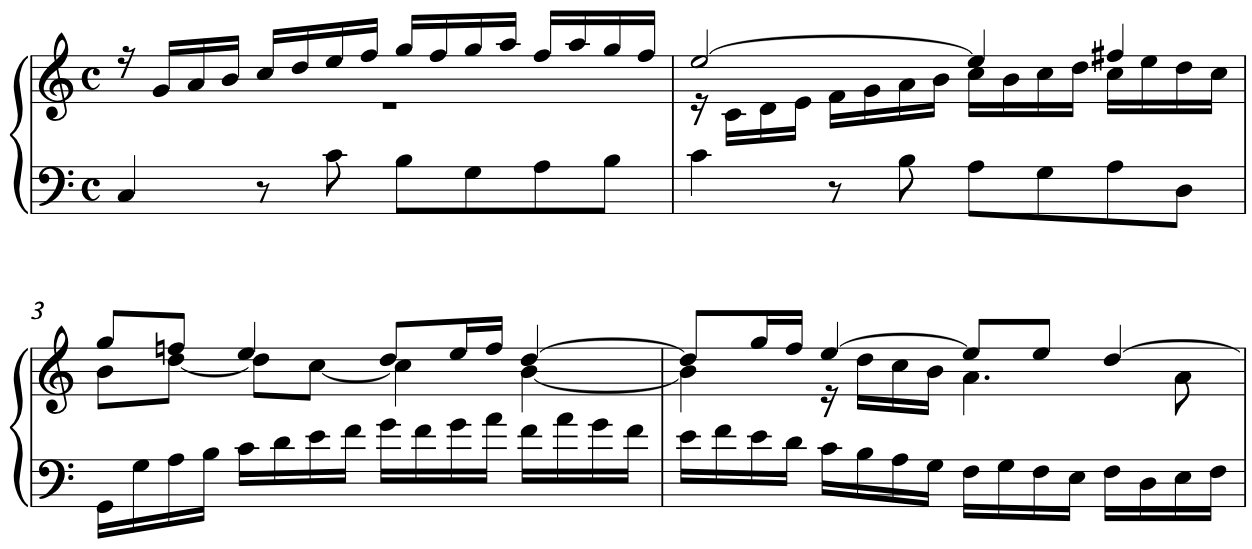

Let’s take a look at the opening measures of Bach’s Sinfonia No. 1. Before we do, go ahead and give it a listen:

Listening Link: Bach: Sinfonia No. 1 in C major, BWV 787

Pretty, yes? This is a relatively gentle piece of literature that sounds peaceful and effortless. What you’re not hearing is that it requires the player to overcome a few fingering bramble patches, which can be a surprise if you’re simply planning to dive in for a quick read-through. See if you can slowly sightread your way through the first couple of measures of this unmarked, urtext version:

Did you run out of fingers? Sometimes difficulty in piano music has little to do with pianistic pyrotechnics, like high-flying arpeggios or sweeping scales, but rather with the deft recreation of musical passages that require specific fingering, exemplified by the music of J.S. Bach. Practicing Bach is a great way to train your mental muscle to internalize precise fingering needs.

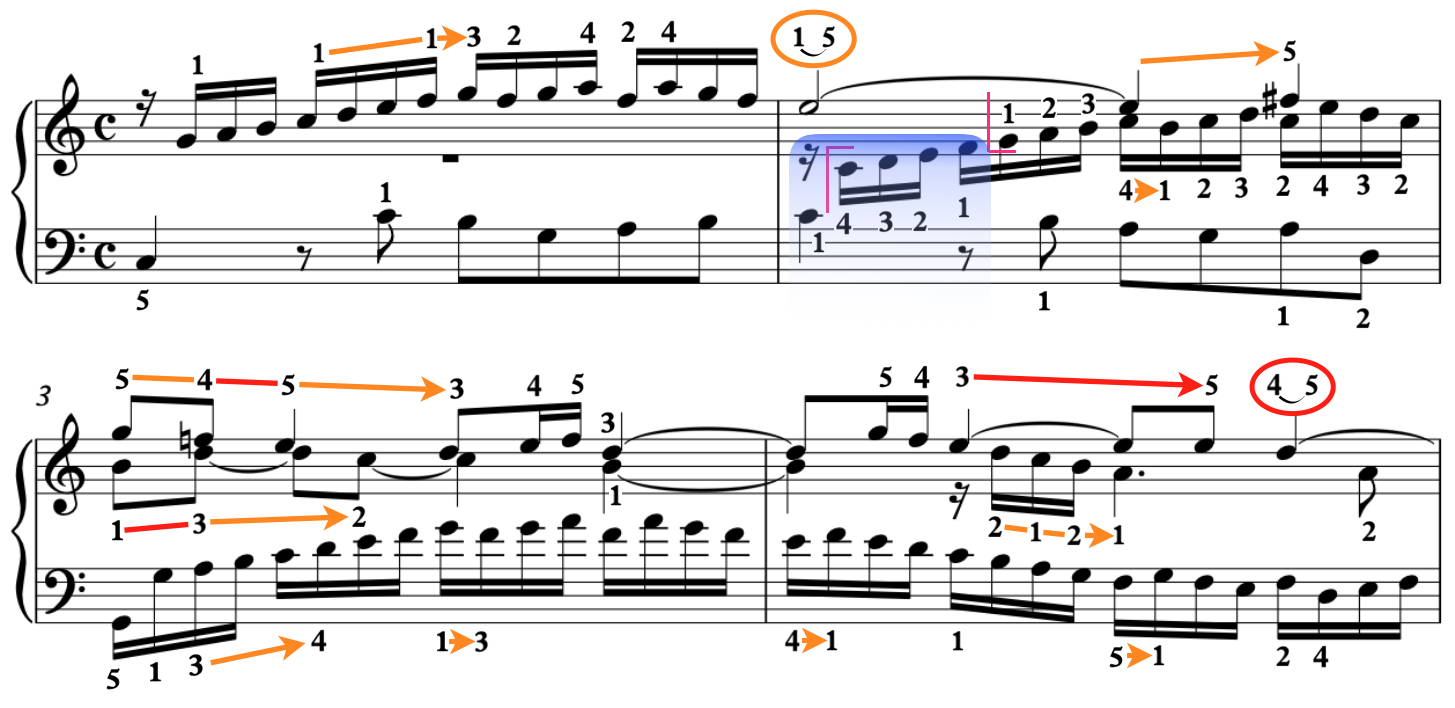

Let’s take a look at this passage with the fingering added. See if you can slowly follow along at the keyboard:

While choices in fingering can be subjective, there are only so many ways we can move our fingers, and, as the above selection demonstrates, sometimes the correct fingering path is very narrow. The arrows between the fingering numbers show spots where the player will likely need to pay extra attention to which fingers are being used, with the orange color indicating slightly unusual movements, and the red color indicating very unusual movements. The circles show fingerings in which the player must seamlessly switch between fingers while holding down a note to re-position the hand for upcoming material. The blue highlighted zone is an area in which the left hand must play the beginning of what at first seems to be a right hand passage, but that no part of the right hand can adequately reach to play smoothly while holding the E on top. The right hand, still holding the E, takes over halfway through the scale, as indicated by the upward bracket.

In many cases what is required from the fingering is predicated on the style of the music being played. In Bach’s music, we often have to use our fingers to hold onto notes while we play others with the same hand, and if we want these passages to flow as cleanly as they should, we need to integrate the particulars of this fingering into our hand choreography. In other words, your hands need to have the movements in their muscle memory, and if the fingering is more complicated, more effort and focus are needed.

The strategic pianist will go through something akin to the passage above, input the fingerings immediately, and never deviate from them. By doing this, the hands learn to move a certain way from the beginning, and before long the movement is automatic and easy. Even for music that doesn’t require such intense fingering to choreograph properly, getting in the habit of learning and sticking to the best fingering should be adopted by every pianist.

Set a Steady beat

Almost all music happens over a steady beat. This beat can be flexible, it can be interrupted by alterations in form or phrase, and in some cases it can be so slow that it doesn’t seem to exist, but it’s almost always there, and to practice without emulating it is a recipe for major performance issues.

Many students find it challenging to accept that our brains can’t efficiently maintain a steady beat. Until we have enough experience with combining multiple practicing tasks into a single effort, our brains will almost always have to leave something out to focus on other things, and the regularity of a steady pulse is usually the first thing to go.

Think about it: How many times have you started a section of music only to stumble at a problem spot? What usually happens? Your beat falters, and you slow the speed to try and manage the unfamiliar information. This is partially a dilemma of practicing too quickly (which will be addressed below), but also one of steadiness. Many students don’t think about starting the piece with a steady beat in mind, and so they have no gauge for what the beat should be to overcome problem areas. This can result in issues with rhythm, coordination, and musical cohesion.

The most obvious way to overcome this quandary is to use a metronome. While you may cringe at the necessity of locking yourself to the aural grid the metronome creates, it is by far the most effective way to ensure that your beats don’t waver while you practice. By removing the need to keep track of the steadiness of your beats, the metronome allows your brain to focus on other practicing tasks. We’ll talk more about how to set the speed of your metronome below, but no matter your speed, the ability to line yourself up to the metronome is a practicing strategy worth the extra effort to incorporate.

If you have no metronome handy, you can establish a beat by counting one out before you start playing (similarly to the way you might when playing with other musicians). Remember that you should be counting at the speed of your intended beat, and, if you find that your tempo is flagging, you’ll know that you’ve found a specific area in need of extra attention.

Break Down

The world of musical study is full of tools, tips, and tactics to help make the music-learning process more efficient. However, practicing musicians often seem to have an aversion to applying any of these aids, preferring instead to pursue their musical objectives through insistent, tactless repetition of as much material as they can possibly get under their fingers.

One of the worst problems with this approach is volume; we learn less effectively when trying to absorb greater amounts of material. This can be challenging to see when you’re deep in the trenches of learning a piece, but make no mistake, unless you’re able to sightread at a performance level, trying to inhale great numbers of notes and measures all at once hinders your practicing efforts instead of helps them.

The solution, as you may have already guessed, is to break down your piece (and pieces of your piece) into more easily digestible components. This can be done in a great variety of ways, many requiring little more than your own ability to detect visual cues.

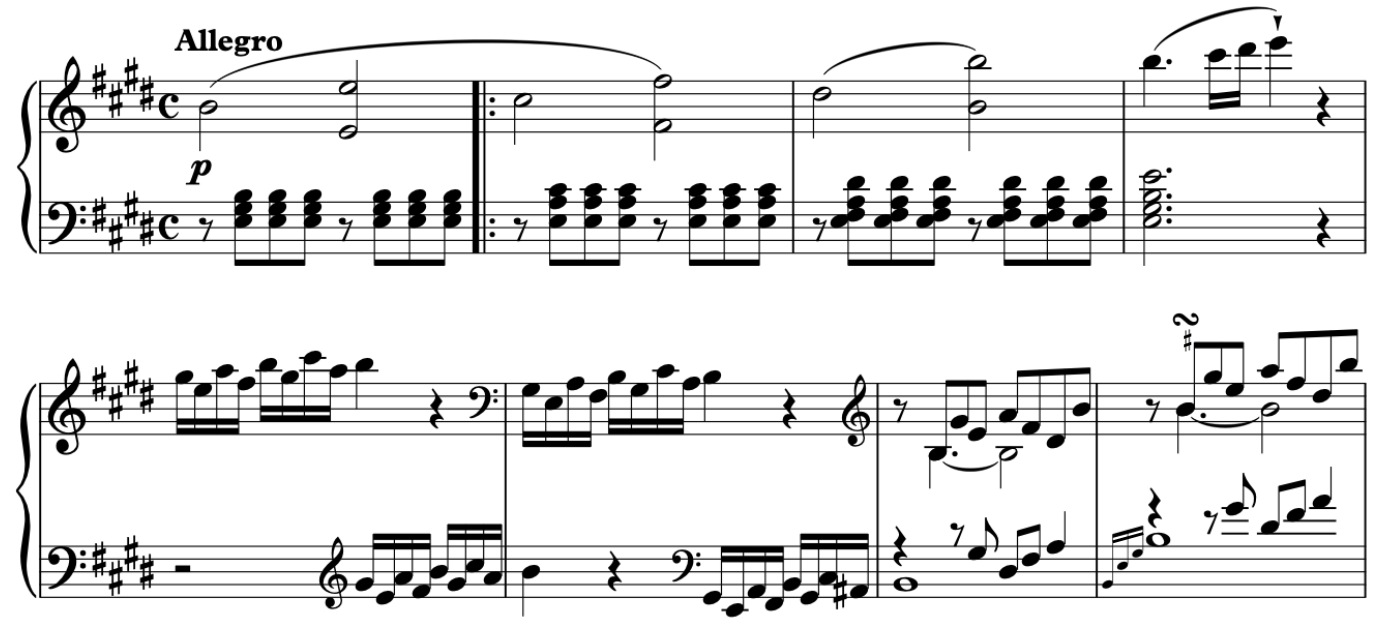

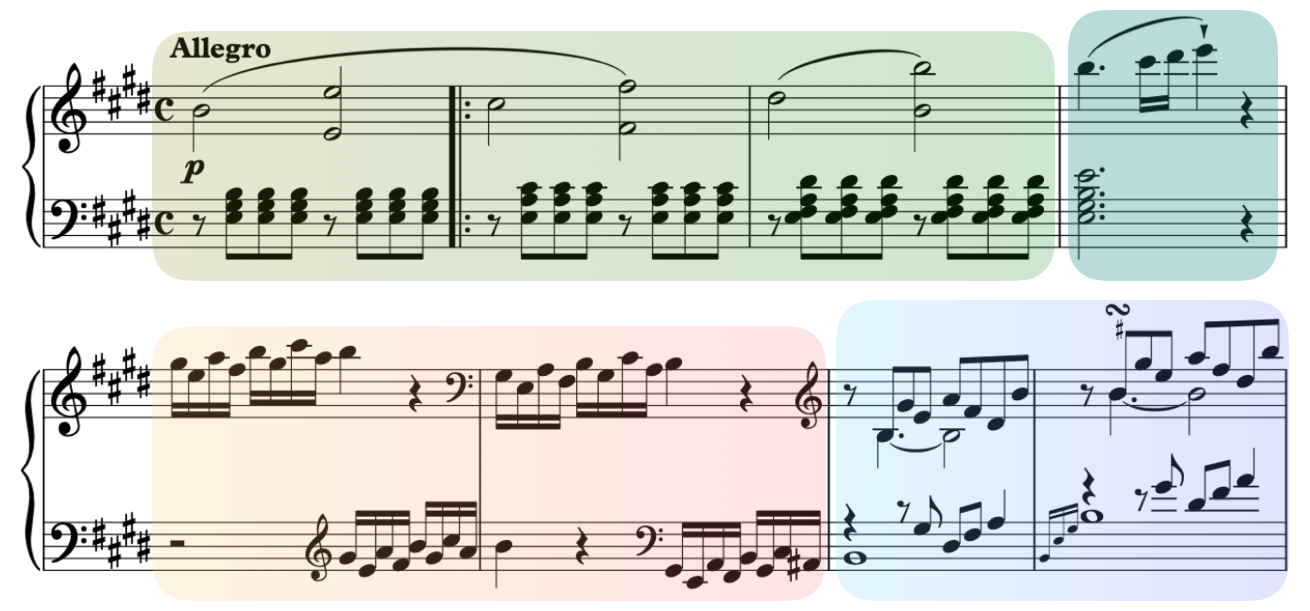

Let’s look at an example. Here are the first eight measures of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 9 in E major, Op. 14, No. 2.:

In case you’re wondering, we have omitted any fingering to make things a little easier to see.

Without even thinking of what the notes might be, can you perceive any areas that stand out visually? Which figures and phrases look like they go together?

Asking questions like these before you start practicing can help direct your attention to sections that can be broken down and worked on as independent units. For example, in this passage we have several visually distinct zones of material, each with its own needs in hand motion:

Once you’ve visually identified sections that look like they can be worked on independently, you can decide how to apply your understanding of the technical or theoretical aspects of music to learn it effectively. You can break things down further by practicing each hand separately, or even by practicing measure-to-measure. If you’re a beginner or even an intermediate player, you’ll probably find that it works well to break your music into two-measure chunks, and then to stitch those together into four-measure chunks, and then eight-measure chunks, and so on.

The goal here is not to be able to play each of these sections at tempo before putting them together, but rather to bring them up to speed once you’ve spent some time infusing your hands with their content at slower speeds. This last point is the topic of our final, and perhaps most important section…

Slow Down

In my years as a piano teacher I’ve seen students make one practicing misstep more than any other: they try to play their music too quickly, too soon.

Admittedly, the urge to play fast is powerful. So many keys! I wonder how fast I can play them? This urge settles early into most pianists’ practicing lives and rarely leaves. Even very experienced pianists can suffer from impatience, and the resulting acceleration of fingers almost always comes with a corresponding dip in the quality of practice. And it doesn’t help that the remedy for practicing too quickly–“slow down”–can be stated with such uninspiring austerity.

Fortunately, there are more detailed methods that you can use to incorporate slowing down into your practice strategy. Instead of simply slowing down to an arbitrary speed, you should try to control the value of slow down so that you can measure it against the goal of building the music up to tempo. Once again, a metronome can be your greatest ally in this endeavor, as no other timing method guarantees that you will know the speed that you’re playing as accurately.

A good first step towards controlling the value of slow down and measuring the tempo to your advantage involves finding two different speeds at which you can play through material: one that is slightly too fast, and one that is slightly too slow. At your slightly too fast speed, you are just starting to make mistakes (missing notes, dropping tempo for difficultly, panning articulations, etc.), while your slightly too slow speed should have you just on the edge of getting impatient. Make the faster speed your goal speed (the speed you want to build up to), and start practicing from the slower speed, aiming to achieve no less than three perfect repetitions of the material before you accelerate your tempo up a notch. If you start making mistakes, slow back down and try again. Depending on the unfamiliarity or difficulty of the material, this process may need to be repeated over several practice sessions, and you may not make your goal speed in the first couple. Make sure that you know the goal tempo of your piece (your initial fast speed might not be it), and use it to help gauge your progress.

Remember, slowing down is a strategy for practicing, but you should be working to build your speed up to the goal tempo of your piece. Much of the music you practice will not be equally difficult throughout; there will be harder sections and easier sections. We tend to play easier sections more quickly, and slow down when we hit harder sections, but ideally we should play no section of music any faster than we we can play its most challenging area. For example, if you’re playing four measures of music, you should only play through those measures as fast as you can comfortably play the hardest parts of those four measures.

Why is this? Remember our little maxim from the beginning of the article, we practice to perform; when we allow ourselves to practice with the “flexible” time of speeding up for the easy bits and slowing down through the hard bits, we’re building that into our performance, and it can be all too easy to think that we’ve mastered a problem spot only to have it fall apart during performance because we never actually worked it up to tempo properly. This kind of performance malfunction is often the result of inadequately developing an understanding of the music through the processes of breaking it down and slowing it down. In other words, if you’ve skimmed the analysis and practiced with tempos that are too fast or inconsistent, you’re likely in for a rough ride…

In fact, the previous three strategies–setting a steady beat, breaking down, and slowing down–create a golden pyramid of first-case remedies for many potential practice issues. Oftentimes, reinforcing your practicing with one or more of these strategies will help you overcome commonly encountered challenges, with slowing down and breaking down being especially effective.

As I tell my students, when in doubt, slow down and break down.

Be Strategic

Practicing is one of the maligned necessities of learning music: few want to do it, but everybody has to do it if he or she strives for musical excellence. Fortunately, the art of practicing is rife with strategies to make the process more manageable. Unfortunately, many of us neglect to incorporate these strategies into our practicing and end up suffering through ineffective music learning as a consequence. We hope that this article has given you a renewed perspective on what some of these strategies are and how you can best use them to your advantage while practicing.

For more articles about practicing, stay tuned to Liberty Park Music!

I play Guitar, Recently I just started to play Piano, this is the best article for me. Thanks for the article.

Learn to play Someone You Love Chords

I play Guitar, Recently I just started to play Piano, this is the best article for me.

Learn to play Someone You Love Chords