Few names are as closely linked to the history and performance of the piano as that of Frédéric Chopin. Called the “Raphael of the Piano,” Chopin composed a rich, diverse array of piano music that ranks among the most performed in the classical music repertory. An important figure in the early Romantic period of Western Classical music, Chopin lived during the artistically fruitful and politically charged early decades of the 19th century, and he crossed paths with many of the leading musical figures of his day. As a pianist, Chopin’s skills are reputed to have been prodigious, and his compositions helped to set new standards of technical and creative mastery for the piano.

In this article we will explore the life and times of this remarkable musician, and provide some context to his life’s endearing work. We will also explore some of the specific characteristics of Chopin’s style as both a pianist and a composer, and attempt to illuminate the identity of the man behind the music.

Chopin's Early Life

Frédéric François (Fryderyk Franciszek) Chopin was born to Mikołaj and Justyna Chopin on March 1, 1810, in the village of Żelazowa Wola, which at the time was a part of the short-lived Duchy of Warsaw. Mikołaj (originally Nicolas) was a French emigrant who had relocated to Poland, making his living as a French teacher and slowly garnering the trust and attention of Warsaw’s wealthy families as a noteworthy tutor. Justyna Chopin was the daughter of a recently deceased local administrator who had been brought on as a housekeeper in the home of one of Mikołaj’s wealthy clients. It was under these circumstances that Mikołaj and Justyna met, married, and commenced the creation of their family.

Despite his French ancestry, Frédéric Chopin would strongly identify with Poland throughout his life, and the violent turmoil sparked by the country’s political instability would become a lasting concern for him. The Poland of Chopin’s time was split between multiple governing powers in the aftermath of the Polish-Russian War and the Napoleonic Wars, and the eastern part of the country in which Chopin was born and raised was under the umbrella governance of the Russian monarchy. That Chopin was to land in the French capital of Paris for much of his adulthood was more of a happenstance than a deliberate decision, but Chopin’s expatriate state of being would greatly influence his social and musical world.

While much of Chopin’s early life was bolstered by this supportive and educative family setting, it was marked by one notable issue: Frédéric Chopin was born frail, and his early contracting of tuberculosis guaranteed that his consistently poor health would limit his physical capacity, both on and off of the performance platform.

Chopin's Early Life

Chopin exhibited a connection to the piano at an early age. After observing the interest her 4-year-old son took in the piano lessons she was giving her eldest daughter, Ludwika, Justyna Chopin began to tutor him as well. It became quickly apparent that Frédéric’s talents were substantial, and that professional tutelage was necessary to help foster them.

Chopin had only two official teachers throughout his life, both of whom proved well suited to aid in the education of their prodigious young pupil. The first of these, a colorful, snuff-loving local piano instructor named Wojciech Żywny (pronounced: voy-check ziv-nay), provided Chopin with a solid foundation of basic technique and historical music context. Żywny introduced Chopin to the 48 preludes and fugues of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, which Chopin memorized early, and would claim as one of his primary influences and inspirations. Chopin’s second teacher, Jósef Elsner, headed Warsaw’s High School for Music (a rival branch of the Warsaw Conservatory, at the time) and instructed Chopin on the principles and techniques of harmony, composition, counterpoint, and orchestration. As a student under Elsner, Chopin would compose his first significant works, including, notably, nearly his entire output for piano and orchestra.

Chopin’s connection to the piano was reflected in his performance and composition skills while at the High School for Music. By the time he graduated, he was one of the finest pianists in Poland. His unique and naturally fluent technique, which he employed to stunning effect during his constant improvising, afforded him the ability to tackle problems at the keyboard that might have otherwise seemed overwhelming for his slight physique and relatively small hands. In addition, he demonstrated a keen talent for composition, and would compose his first significant works before departing the school, including both his piano concertos, his Piano Trio in G-minor (Op. 8), a large number of solo piano pieces, and his impressive Variations on Mozart’s “Là ci darem la mano,” for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 2. After receiving a copy of the “Là ci darem” Variations, Robert Schumann extolled Chopin’s acumen with the now immortalized declaration: “Hat’s off, gentlemen, a genius!”

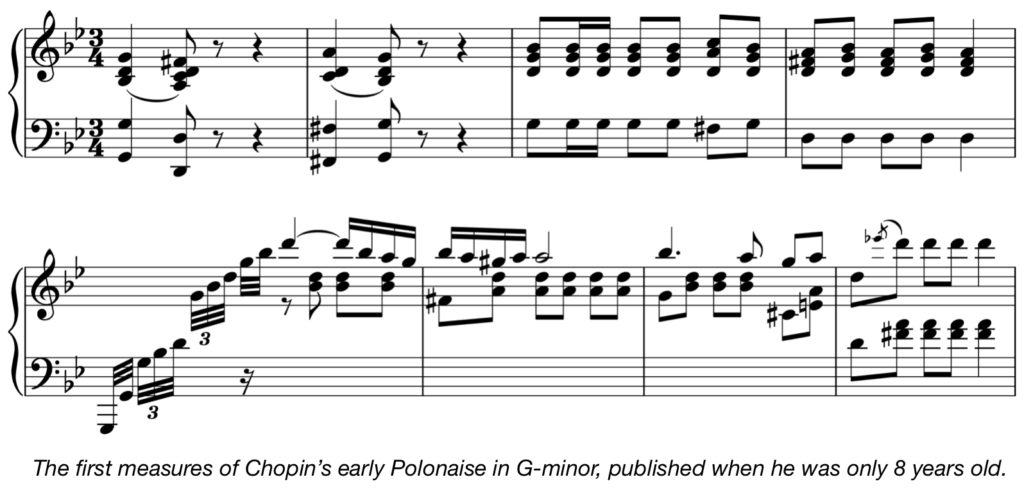

As with his piano skills, Chopin’s talents as a composer had also revealed themselves in his youth, with his earliest published work, a Polonaise in G-minor, appearing in 1817, when Chopin was only 8 years old:

Listening Link: Polonaise in G-minor, Op. 2

Later on, during his time at Elsner’s High School of Music, Chopin spent copious amounts of time in a local music shop perusing new music. This is where he probably encountered the nocturnes of Irish composer John Field, a genre he would go on to adopt and produce some of his most famous works within.

Some of Chopin’s earliest recognition as a maturing artist came out of his adolescent sojourns to Berlin and Vienna, the latter of which, home to such titans of music as Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, was considered the musical capital of the world. Chopin’s experience with the genteel attitudes and formal standards of the aristocracy (along with the aristocratic connections he carried with him from Poland), afforded him access to the courtly chambers and salons of the metropolitan elite, where he charmed his well-to-do listeners with his virtuosic technique, captivating compositions and improvisations, and cultivated personal manner. From Chopin’s visit to the salon of Prince Antoni Radziwiłł (who was a fine composer and cellist himself) we possess the following later-century depiction:

Chopin would largely shy away from major engagements throughout his life, giving only a few dozen performances in front of large audiences. The scene above portrays Chopin in a performance setting that was much more to his preference: intimate, comfortable, and familiar.

Upon returning from his travels abroad and after exiting the Warsaw High School for Music, Chopin realized that his professional and artistic destiny could not be confined to the borders of his home country, and he began preparations to depart for more fruitful environments. Chopin, infamous amongst his close friends for his powers of procrastination, took his time deciding where to relocate, but ultimately settled on the stable, prosperous city of London.

This decision was partially made by choice, but also by omission; Chopin’s original choices were Italy and Paris, but the Italian peninsula was experiencing political unrest, and the Russian authorities were reluctant to issue travel documents to a known sympathizer of Polish patriotism to a country with unfriendly Russian sentiments. While Chopin would never go so far as to partake in any genuinely revolutionary activities, he identified with the plight of his fellow Polish nationals against the overbearing yoke of Russian rule, and made no attempts to hide his pro-national relationships. Little did he know, the ignition of events in the wake of his exit from Poland would turn his expedition for professional elevation into lifelong exile.

Chopin the Man

Our description of Chopin and his character is compiled from a wealth of correspondences, diaries, and personal accounts penned by Chopin himself, and by his contemporaries.

Evidently precocious as a child, Chopin internalized his family’s respectful, well-mannered values from a young age, and his life-long association with elite patrons and friends fortified this sense of propriety. He was reserved, well-spoken, intelligent, and always immaculately groomed. He had a developed and somewhat surprising sense of humor, which he would employ when critiquing the many extravagant personalities and practices he encountered throughout his life. His powers of witty intellectual contempt would often come to bear in the criticism of what he perceived to be the world’s mistakes, as can be seen in his missives addressing the often inflated environment of the Parisian musical world.

For those privileged to know Chopin within his personal environment, he would occasionally display a masterful talent for mimicry, which he used to mock the more ostentatious fads of the virtuoso world. Particularly in his private correspondence, he could be outwardly emotional, effusive, and quite earnest; however, this version of Chopin was rarely observed by the outside world. From his later lover and caretaker, George Sand, we read that Chopin was virtually addicted to habit and routine, and could become agitated at even the smallest interruption of his daily schedule.

Chopin’s illness was the silent overlord of his world, and while he would occasion to complain of his suffering to family and close friends, to the outside world he presented an attitude of stoic acceptance. He often insisted that the world remain ignorant to the intensity of his health struggles, and hid his symptoms behind a carefully tailored image of statuesque dignity.

Departure from Poland

Chopin departed Warsaw for the last time on November 2, 1830. Not one month after his departure, on November 29, the Warsaw Uprising began, throwing Poland into ten months of some of the worst turmoil and strife in the country’s already turbulent history.

While the details of the Warsaw Uprising are beyond the scope of this article, its significance to Chopin is important for a few reasons. First, it prevented Chopin from returning to his homeland for the rest of his life. Secondly, it cast Chopin’s frame of mind into a frazzled tide of concern and despondence over the well-being of his friends and family. After receiving word of the strife, Chopin was eager to return to Warsaw in support of those closest to him, but a letter of admonition from his family deterred him, and he continued westward, finding solace in his composition and letter writing. Quite a few notable compositions were either completed or in production during this period, including the early mazurkas of Op. 6 and Op. 7, and the tempestuous Scherzo in B-minor, Op. 20, which was not published until 1835.

Listening Link: Mazurka No. 7 in A-minor, Op. 7, No. 2

Listening Link: Scherzo No. 1 in B-minor, Op. 20

Chopin’s travels took him through a number of significant cities, where he often stayed for short durations, making acquaintances and trying to manage the anguish of hearing the news of his continuously deteriorating homeland. Passing once again through Vienna, Chopin continued on through Munich, and landed for a week in the small German city of Stuttgart. Here he unleashed the despair and torment he felt concerning the fate of Poland into a notebook that has come to be known as the “Stuttgart Diaries,” in which he states, “I am…only able to pour out my grief at the piano.” This has come to be regarded as a kind of declaration of conviction and dedication for his art, which would only increase in ambition and depth in the years to come.

Chopin arrived in Paris on October 5, 1831. While his travel documents indicated that his official destination was “To London via Paris,” and despite the fact that Chopin had no intention to linger for long in France, the country of his father’s birth would become his home and place of exile for over fifteen years.

Life in Paris and Middle Years

Chopin’s first months in Paris witnessed him at once marveling at the combination of splendor and squalor contained within the city, and worrying about finding a place amongst the maelstrom of people and happenings. Aside from its standing as a mecca of European culture, power, distinction, and debauchery, Paris was also experiencing a period of unrest, as its monarch, King Louis-Philippe, popularly aligning himself with the people as their “citizen king,” contended with dissenting factions that did not believe he was the populist ruler he purported to be. Amid the excitement, the first waves of the “Great Emigration” were making their way into the city from the disintegrating Poland, and among them came a number of Chopin’s own companions, several of whom had connections within the city. These contacts, a couple of letters of introduction by Elsner and Dr. Malfatti, as well as the sheer magnificence of Chopin’s skills and compositions helped him to blend with the musical (and non-musical) elite of the city. Thus began Chopin’s years of attending Paris’s famed salon gatherings.

The cast of characters Chopin was to become acquainted with during this time reads like a “who’s who” of Romantic royalty: Berlioz, Liszt, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Clara Wieck (who was to become Clara Schumann), Rossini, as well as figures less known in our times but plenty famous in their own such as Henri Herz, Auguste Franchomme, Ferdinand Hiller, and acclaimed pianist Friedrich Kalkbrenner, with whom Chopin would strike up a lasting, if slightly stiff, friendship. A notable result of the relationship between Chopin and Kalkbrenner was Chopin’s introduction to the piano maker Camille Pleyel, whose instruments Chopin would come to favor over all others for the remainder of his life.

Chopin's Pianos

The pianos of Chopin’s time were different from modern pianos. The stouter, more muscular sound and action that characterizes many modern instruments had yet to evolve, so the instruments on which Chopin played were generally lighter to the touch, and more metallic in sound. They also tended to be shorter. While Chopin did have seven octave instruments available to him, his choices typically led him to the 78-key, six and a half octave instruments for the other qualities they possessed.

Chopin’s favorite boyhood piano was a Buchholtz grand that his father purchased for him, which was unfortunately destroyed by Russian soldiers during the January Uprising of 1863. While Chopin would come to appreciate the instruments of Conrad Graf during his initial travels to Vienna, it would be the instruments of Camille Pleyel that ultimately won him over. By Chopin’s reckoning, the Pleyel piano offered him an unparalleled depth of expressive possibilities, and the most control across the spectrum of dynamic range. Pleyel often went out of his way to ship his pianos to Chopin’s location, even if that location was challenging to reach. Chopin’s final Pleyel, loaned to him by the instrument maker in the final months of his life, is located in the Chopin Museum in Warsaw.

Chopin’s financial fortunes, which had always been dependent upon the good graces of his family, followed his social and artistic ones in turning for the better during this time. While the exact narrative is shrouded in some uncertainty, at some point Chopin was privileged to interact with one of the most powerful banking families in Europe, the Rothschild family. While attending a soirée in the home of Baron James de Rothschild, Chopin’s playing skills (and polished demeanor) so impressed the blue-blooded audience that he soon had a number of high-paying lessons, and a near endless supply of aristocratic sons and daughters to fill out his teaching schedule.

Within a few years Chopin had distinguished himself amidst the members of the Parisian cult of pianistic virtuosity that was all the rage in the city, known as “the flying trapeze school.” While a number of high quality composer-pianists, such as Liszt and Charles-Valentin Alkan, are often categorized under this derisive nomenclature, many others presented the world with little beyond ear-catching musical fireworks, and Chopin did not care to be listed amongst their ranks. Fortunately, Chopin’s enchanting improvisations and unique technique, in addition to the intricate richness of his growing repertory of compositions, set him apart from the ostentatious musical flamboyance of his fellow virtuosi.

Chopin the Pianist

Chopin was considered one of the greatest pianists of his day - no small feat considering that his musical counterparts included legendary players such as Franz Liszt, Sigismond Thalberg, and Friedrich Kalkbrenner. His light, nuanced, and precise style was fueled by his desire to present keyboard virtuosity as being in service to the expression of musical substance, rather than to simple, flashy displays of technical skill.

The sound of Chopin playing is purported to have seemed “small” in the wide open spaces of the concert hall, and was better suited to the more intimate interiors within which he did most of his performing. As was mentioned earlier, Chopin disliked the larger concert hall setting, and made little attempt to tailor his playing to it. Chopin is also said to have been a relatively motionless player, and he often mocked virtuosi who incorporated theatrical movements into their performance.

In addition to written testimonies, we can glean Chopin’s playing style from his own compositions, the specific instructions within them (e.g. fingering, dynamics, etc.), and his own teachings. Works such as the two series of “Studies” (Études), Op. 10 and Op. 25, clearly exhibit some of the musical techniques Chopin sought to regularly employ and surmount, and a veritable library of mazurkas exist to show off Chopin’s more casually remarkable creativity.

Listening Link: Etude in C-major, Op. 10, No. 1

Listening Link: Etude in G#-minor, Op. 25, No. 6

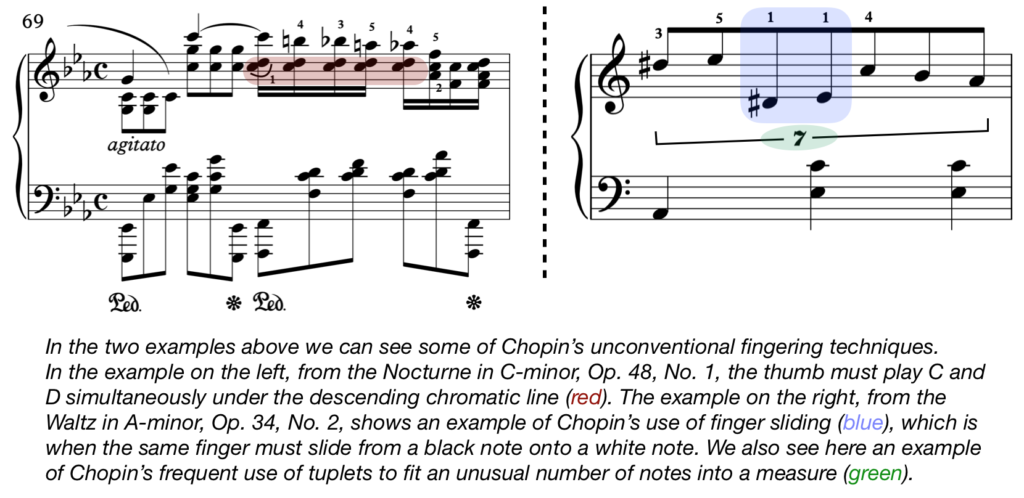

Chopin often employed unconventional finger techniques to achieve musical goals, which can be seen by inspecting the fingerings on numerous compositions:

Listening Link: Nocturne in C-minor, Op. 48, No. 1

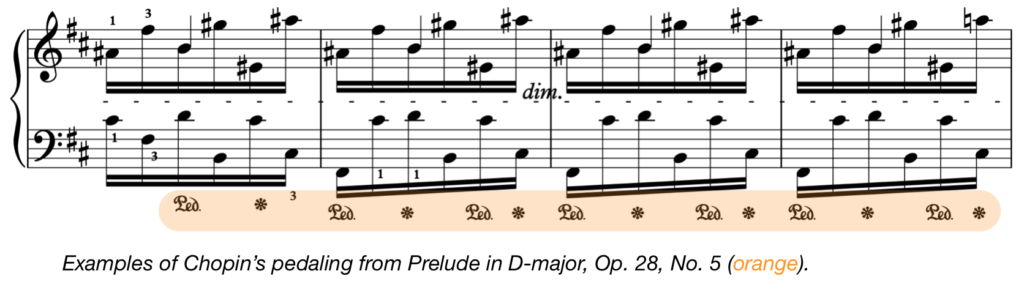

Chopin’s playing was also noted for its combination of clarity and resonance, which was aided by his use of a “fluttering” pedal technique, the gist of which we can surmise by observing his written pedal markings:

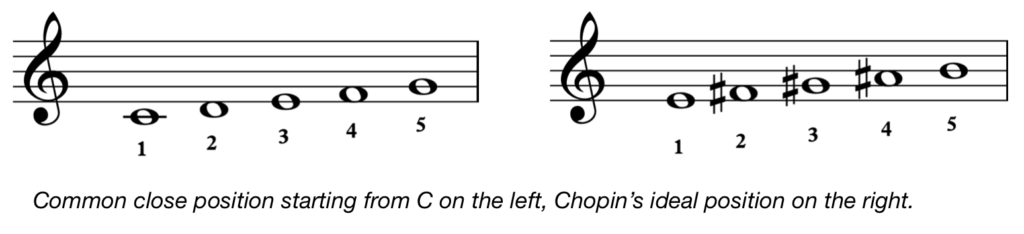

While Chopin never completed a fully written piano method, his unfinished “Sketches for a Method” provides some insight into his thinking about piano playing. Notably, Chopin believed that the most comfortable and natural close position for the hand was on the notes E, F#, G#, A#, and B, and that the value of this physical consideration was worth more than the traditional, theoretical beginner’s approach of placing the fingers on the white notes rising up from the note C. This mode of thinking was both revolutionary and controversial, as no one before Chopin had thought to question the C-major status quo. As anyone who has started their piano studies with any of the great variety of piano method series can attest, this idea failed to take hold; however, at least one eminent piano pedagogue in history (Heinrich Neuhaus) has claimed that Chopin’s way should supersede the age-old thinking.

Give it a try: place your fingers over both positions at a keyboard. Which position do you find more comfortable, the traditional C close position, or Chopin’s position?

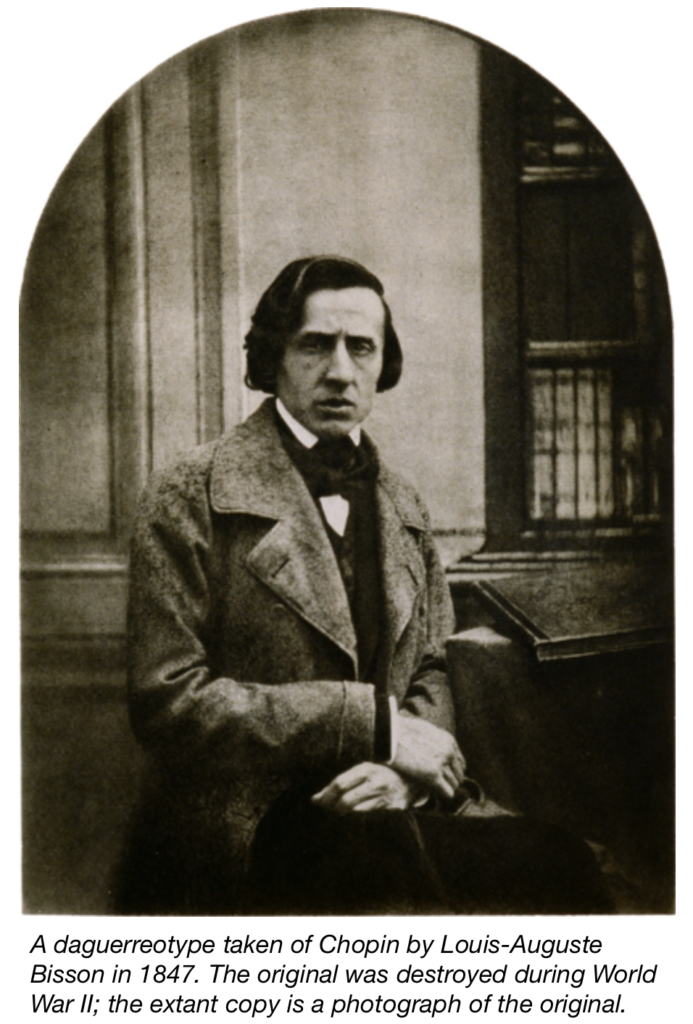

A commonly noted curiosity about Chopin is the relatively small size of his hands, which were nonetheless supple enough to spread and leap across great distances at the keyboard with remarkable accuracy and ease. At Chopin’s death, a mold was taken of his left hand at the same time as his death mask was being cast, leaving us with a life-sized sculpture of one of the most skillfully used tools ever to touch the keyboard.

In the years between 1832 and 1837, Chopin continued to compose and fortify his reputation amongst the musical forerunners of Paris. While he did give a number of large-scale public performances, he preferred the less formal and populated environments of the salons or private gatherings. He briefly visited London in 1937, partially to assuage the ill-feelings he was suffering as a result of an aborted engagement to the sister of one of his childhood companions, and published some significant and classic works such as the G-minor Ballade, Op. 23, and his second book of Études, Op. 25.

Listening Link: Ballade in G-minor No. 1, Op. 23

In 1938, Chopin entered into a relationship with the writer George Sand, who was famed among the salon-going cliques for her outgoing personality, gender-bending attire, and radical ideals. While the romantic dynamic of their relationship would diminish within a year of their union, Sand assumed the role of caregiver for Chopin and his delicate health until their split just a few years before his death.

Chopin’s success and fame grew exponentially throughout the 1840s, with each of the relatively few public concerts he gave bringing him closer to the feverish adoration enjoyed by his peer, Franz Liszt. Yet while Chopin certainly appreciated the professional recognition and artistic success, he likened the accolades to those of a circus audience—one that was far more interested in the glamour of the show than the content of the acts, as seen in his reaction to Liszt’s review of one of his concerts.

On April 26, 1841, Chopin gave his first concert in a number of years to a packed house at the Salle Pleyel. Taking over for the normal music reviewer for such an event, Liszt lauded the concert with poetic abandon: he praised the music, the venue, the audience, and of course the great composer and performer himself - Chopin!… It was a eulogy of epic proportions, which was at the heart of Chopin’s criticism and concern; the proportions were too epic, too effusive in their acclaim, and perhaps just a little too patronizing in their undertones coming from such a grotesquely popular superstar to a somewhat less popular one. It was a wariness of the elite musical realm of critique that Chopin would retain throughout his prosperity.

Chopin bolstered his success during this time by maintaining a busy teaching schedule, and through the publishing of his compositions. Several of Chopin’s works from this period are considered masterpieces, including the Ballade in F minor, Op. 52, the Polonaise in Ab-major, Op. 53., and the Scherzo in E major, Op. 54.

Chopin the Composer

Chopin’s compositional output was inextricably tied to his pianism, and almost everything he wrote focused on the musical possibilities of the piano. His improvisations served as essential inspirations for the works he penned, and he could not effectively compose without access to a piano. With the exception of several pieces for piano and orchestra, some chamber music, and a number of songs, Chopin’s oeuvre is entirely for solo piano.

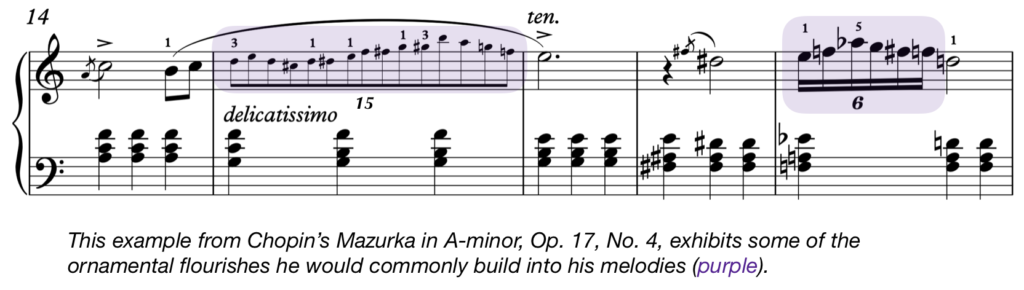

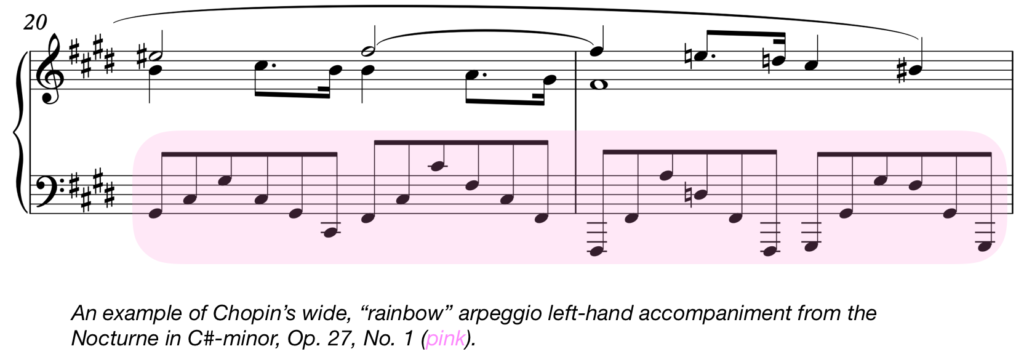

It is important to recall Chopin’s skill as an improviser when considering his compositions, as many of the most identifiable characteristics of his style can be traced back to their improvisatory origins. The vast, contoured fioriture (“flourishes”) of ornamentation ubiquitously decorating Chopin’s melodies are recognizable as the solidified molds of impromptu elaborations, as can other features such as polyrhythms and melodic variations. Many of these elements are undoubtedly manifestations of Chopin’s love of opera, and in particular the practices of fioratura singers:

Chopin’s left hand accompaniment for all of these dexterous displays also possesses many recognizable consistencies, from arcing “rainbow” arpeggios to relatively simple, waltz-style accompaniment:

Listening Link: Nocturne in C#-minor, Op. 27, No. 1

From a structural and emotional perspective, the music of Chopin blends a freedom from expressive inhibition with an almost Classical sense of narrative. A single piece can possess vast juxtapositions in emotional expressivity, and at the same time still be contained within forms as simple and balanced as ABA. Indeed, this particular form finds its way into a number of Chopin’s preferred genres, as it affords a formal opportunity to present such contrasts. In other cases, such as in several of the Ballades, Polonaises, and Scherzos, Chopin’s formal design is much more creative, though no less carefully executed.

While many of Chopin’s pieces require a high level of skill to properly execute, Chopin was disdainful of music that valued technical virtuosity over musical substance. He believed that technical skill and musical depth should be inseparable qualities, and that even when striving for highly dense or challenging results, the truth of the music should be in its design and narrative, not in its theatricality. This mentality is perhaps best represented by the aforementioned Études, Op. 10 and Op. 25, which could have easily joined the second tier rank-and-file of the numerous piano technique studies published around the time (Czerny’s School of Velocity, or Clementi’s Gradus ad Parnassum, to name a few) but have instead become a part of the classical music cannon, regularly recurring in significant performances and recordings.

Chopin’s compositional process could be a thing of intense labor and inner turmoil. He would often be struck by a bolt of inspiration, only to agonize over minute details for great lengths of time. In some cases, Chopin would simply come back to his original idea, having spent days, or even weeks over the same page of music.

While Chopin’s music is often considered an ideal example of Romantic music literature, he was often critical of many of the presiding Romantic trends of his time. In particular, Chopin found the habit of assigning extra-musical import to music to bolster its appeal to the listeners particularly distasteful, and he almost always detested its application to his own music. In almost all cases, assignments of worldly inspiration to Chopin’s music (such as the ferocious, “Winter Wind” evoking passages of the Étude in A-minor, No. 11, or the constant tapping of raindrops supposedly represented in the “Raindrop” Prelude in Db-major, No. 15), are given by outside interpreters such as critics or publishers. For Chopin, the music spoke for itself and needed no qualifying translation from within the precincts of other art forms.

Chopin's Final Years

The presence of the tuberculosis that would contribute to Chopin’s passing became increasingly noticeable in his final years, and not always through its effects on his own health. In May of 1844, Chopin’s beloved father, Mikołaj Chopin, succumbed to the disease in Warsaw, and just over a year later word reached Chopin that his most notable student, the young prodigy Carl Filtsch, had fallen prey to it in Venice.

The presence of the tuberculosis that would contribute to Chopin’s passing became increasingly noticeable in his final years, and not always through its effects on his own health. In May of 1844, Chopin’s beloved father, Mikołaj Chopin, succumbed to the disease in Warsaw, and just over a year later word reached Chopin that his most notable student, the young prodigy Carl Filtsch, had fallen prey to it in Venice.

In addition to these foreboding medical events, Chopin’s relationship with George Sand had begun to deteriorate, and in 1847, after a final falling out in which Chopin appeared to take the side of Sand’s fiery daughter over hers in a family conflict, two separated. The effects of these happenings were devastating to Chopin, and in their aftermath he remained depressed for some time.

Fortunately, Chopin still had a healthy coterie of friends and associates to support him through these trials. Unfortunately, the intensity of Chopin’s illness was steadily waxing, and the dichotomy between the successes of his professional life and the burdens of his personal one became increasingly stark.

Tensions surrounding the French monarchy boiled over in 1848, and the masses rebelled against the shallow rule of King Louis-Philippe. This event ignited a vast wave of revolutions throughout Europe, in what has come to be called the “Spring of Nations.” For Chopin, the flight of many of his steady aristocratic patrons out of Paris meant that his income would be severely stymied. After a bout of cholera struck the city in the wake of the political upheaval, Chopin left the chaos of Paris for the relative stability of Britain, where he performed, mingled with royalty, and enjoyed his welcome exposure to British admirers. Consistent with many of Chopin’s endeavors at this time, the trip was significantly better for his mind and spirit than his body, and, by the time he made his final return to Paris seven months later, his health was on the verge of collapse.

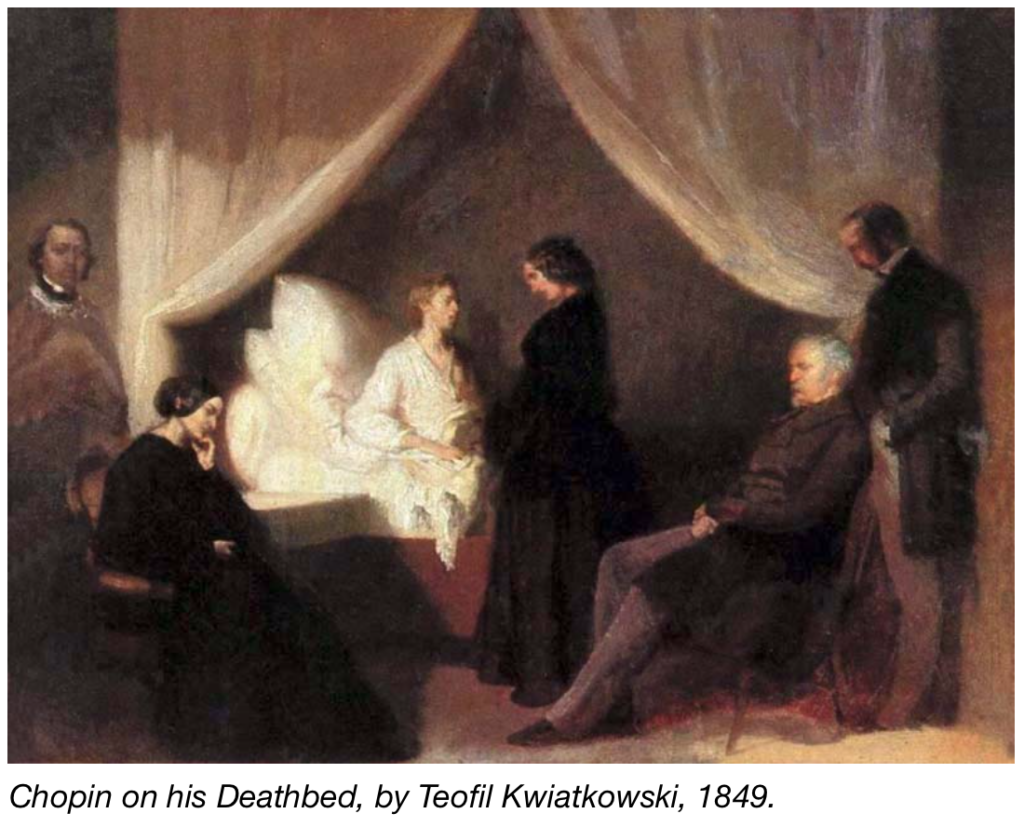

Chopin’s passing was a slow process, and in the interim he was attended by a number of medical professionals, a constant string of well-wishers, and his close circle of friends. One figure to take position in Chopin’s resting quarters was the artist Teofil Kwiatkowski, who provides us with an oil rendition of the final scene (done from memory after his drawings of the room were seen by devoted Chopin pupil, Jane Stirling, who provided much of the financial support for Chopin’s final months, and for his funeral).

Chopin’s passing was a slow process, and in the interim he was attended by a number of medical professionals, a constant string of well-wishers, and his close circle of friends. One figure to take position in Chopin’s resting quarters was the artist Teofil Kwiatkowski, who provides us with an oil rendition of the final scene (done from memory after his drawings of the room were seen by devoted Chopin pupil, Jane Stirling, who provided much of the financial support for Chopin’s final months, and for his funeral).

Chopin died in the early morning hours of October 17, 1849. His funeral, which was delayed until October 30, was attended by upwards of 4,000 people, and, per Chopin’s request, was accompanied by Mozart’s Requiem, which had not been heard in Paris for almost ten years. Famously, while his grave is in the Père-Lachaise cemetery in Paris, his heart was removed and returned to Poland, where it remains interred in a crypt in Warsaw.

Conclusion

Robert Schumann once wrote of Chopin: “If the mighty autocrat of the north knew what a dangerous enemy threatened him in Chopin's works in the simple tunes of his mazurkas, he would forbid this music. Chopin's works are canons buried in flowers.”

It’s exactly the kind of language Chopin disparaged, but Schumann was not necessarily wrong in his assessment. Chopin is popular amongst modern listeners for the beauty of his melodies and textures; however, within the elaborate ornamentation and the parlor-room time signatures, there lies a great, deep ocean of musical depth and content. It is the reason why Chopin’s music has survived for nearly two centuries at the pinnacle of musical regard, and why his works continue to inspire hoards of young players generation after generation.

Thanks for reading this article, and be sure to keep an eye out for more articles in our Composer Bios series here at Liberty Park Music.