The Modern Period in Western music history lasted from approximately 1890 to 1945. As with Romanticism, Modernism is both a historical time period as well as a philosophical aesthetic. In everyday conversation, “modern” typically means current or recent. As a term referencing music, Modernism was first used by critics to describe forms of musical expression adhering to the radical changes happening at the end of the 19th century and into the 20th century. Unlike the terms “Romanticism” or “Classicism,” Modernism describes relatively few unifying musical traits, the sounds of Modernism range from the wistful and bucolic, to the bizarre and jarring.

Historical Context

Because Modernism was a reaction to the events of the late 19th century and early 20th century, it’s helpful to understand the great degree of social and political upheaval that was happening during these decades. The political revolutions sparked in the latter half of the 19th century continued, spiraling into military conflicts such as the Franco-Prussian War (1870), the Spanish-American War (1898), and the First World War (1914-1918) which was known at the time as the “Great War” and the “War to end all wars.” Additional major events included the Russian Revolution (1917), the Spanish Flu (1919), the Great Depression (beginning in 1929), the rise of Joseph Stalin as dictator of the Soviet Union (1929-1953), the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Germany (1933), and the Second World War (1939-1945) which ended with the dropping of the atomic bomb on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945.

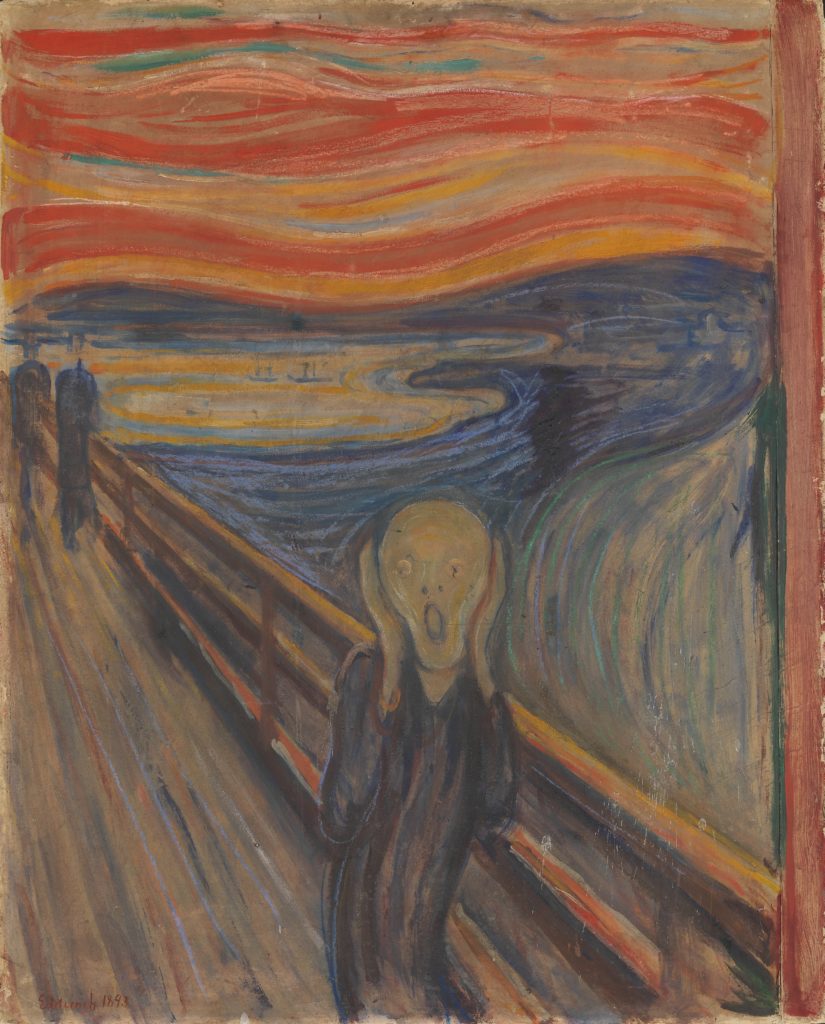

From a historical perspective, the sheer amount of death and destruction during these 55 years was unprecedented, and many in the artistic world came to feel that the old ways of representing the human experience were no longer qualified to handle this terrifying new reality.

Not everything, however, was terror and suffering. Modernism derived great inspiration from the many scientific achievements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Charles Darwin’s seminal work of evolutionary theory, (1809-1882) On the Origin of Species (1859) challenged religious beliefs concerning how life came to be. Through his psychoanalytic explorations of the human psyche, Sigmund Freud proposed that humans were irrational, subconscious forces, driven largely by hidden desires and drives. Then, with Albert Einstein’s (1879-1955) theories of relativity in1905 and 1915, our perceptions of time and space were fundamentally changed. Additionally, the inventions of recorded sound, the telephone, automobiles, and airplanes resulted in major changes to how the world communicated and operated.

Modernist composers thus began to challenge what was possible to do with music, experimenting with a variety of ways of constructing music. Modernist composers saw themselves as the “avant-garde” or front-line troops working to advance music through their sound experiments. Many of these composers experimented with musical sound through timbres, rhythms, and tonality. One of the few unifying traits of musical Modernism was the rejection of functional tonality laid out by Jean Philipe Rameau in his 1722 treatise. Composers at the end of the 19th century broke the rules of tonal harmony to explore different sound colors, new ways of organizing sound, polytonality, and even post-tonality. We’ll discuss the different sound experiments of the period as we introduce four of the most prominent styles of Modernism: Impressionism, Primitivism, Neoclassicism, and Atonality.

Impressionism

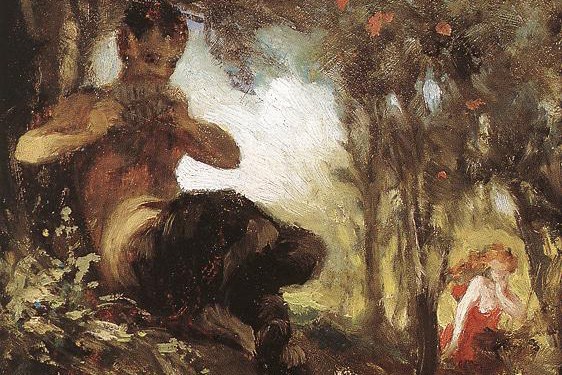

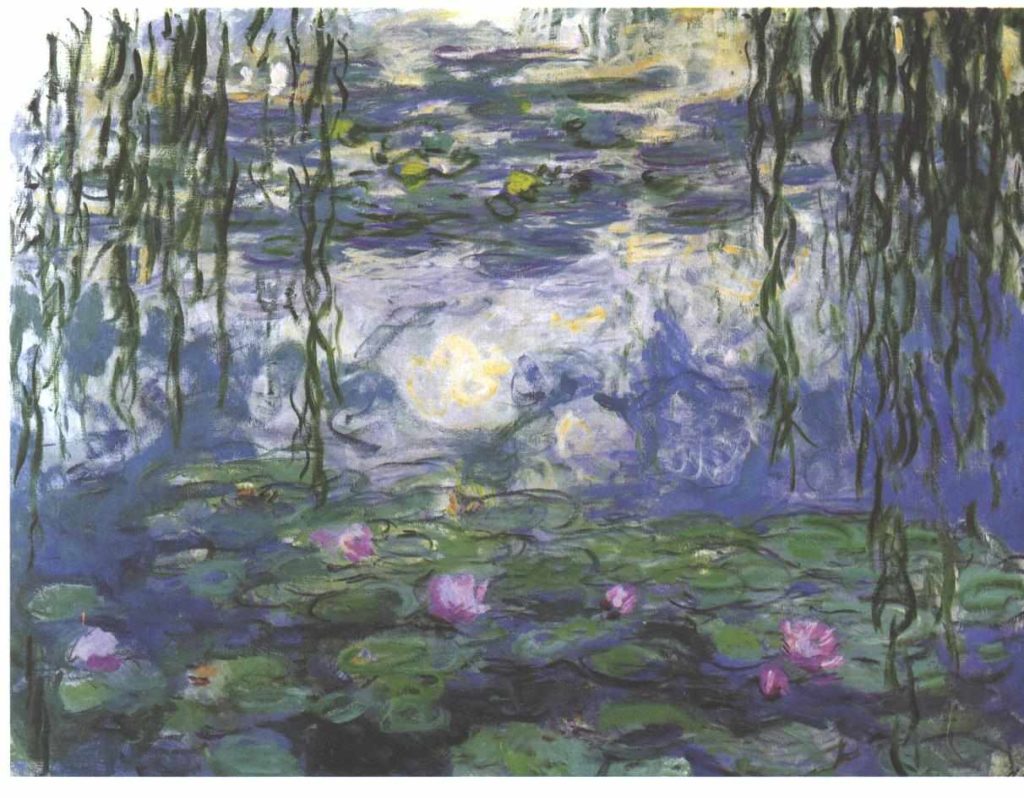

The first of these styles, Impressionism, is seen as both an outgrowth of Romanticism in general, and a reaction against German Romanticism specifically. Impressionism was first recognized in French painting through artists like Monet, Manet, Degas, Cezanne, and Regnault, whose works were seen not so much as depicting the world as it was, but representing an “impression” of reality. Like the painting and poetry aspects of the movement, musical Impressionism “suggested” its objects through innovative sound colors, an avoidance of a strict meter, and the use of non-functional harmony. An example of Impressionism is Claude Debussy’s Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun from 1894, based on the poem by symbolist Stephane Mallarme. Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun is a single movement symphonic poem that focuses on instrumental solos whose tone colors blend into each other throughout an airy, open orchestral framework. The melody contains dotted quarter notes, sixteenth notes, and triplets, disrupting the sense of time and forward motion, and providing a dreamy impression of Mallarme’s poem.

The first of these styles, Impressionism, is seen as both an outgrowth of Romanticism in general, and a reaction against German Romanticism specifically. Impressionism was first recognized in French painting through artists like Monet, Manet, Degas, Cezanne, and Regnault, whose works were seen not so much as depicting the world as it was, but representing an “impression” of reality. Like the painting and poetry aspects of the movement, musical Impressionism “suggested” its objects through innovative sound colors, an avoidance of a strict meter, and the use of non-functional harmony. An example of Impressionism is Claude Debussy’s Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun from 1894, based on the poem by symbolist Stephane Mallarme. Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun is a single movement symphonic poem that focuses on instrumental solos whose tone colors blend into each other throughout an airy, open orchestral framework. The melody contains dotted quarter notes, sixteenth notes, and triplets, disrupting the sense of time and forward motion, and providing a dreamy impression of Mallarme’s poem.

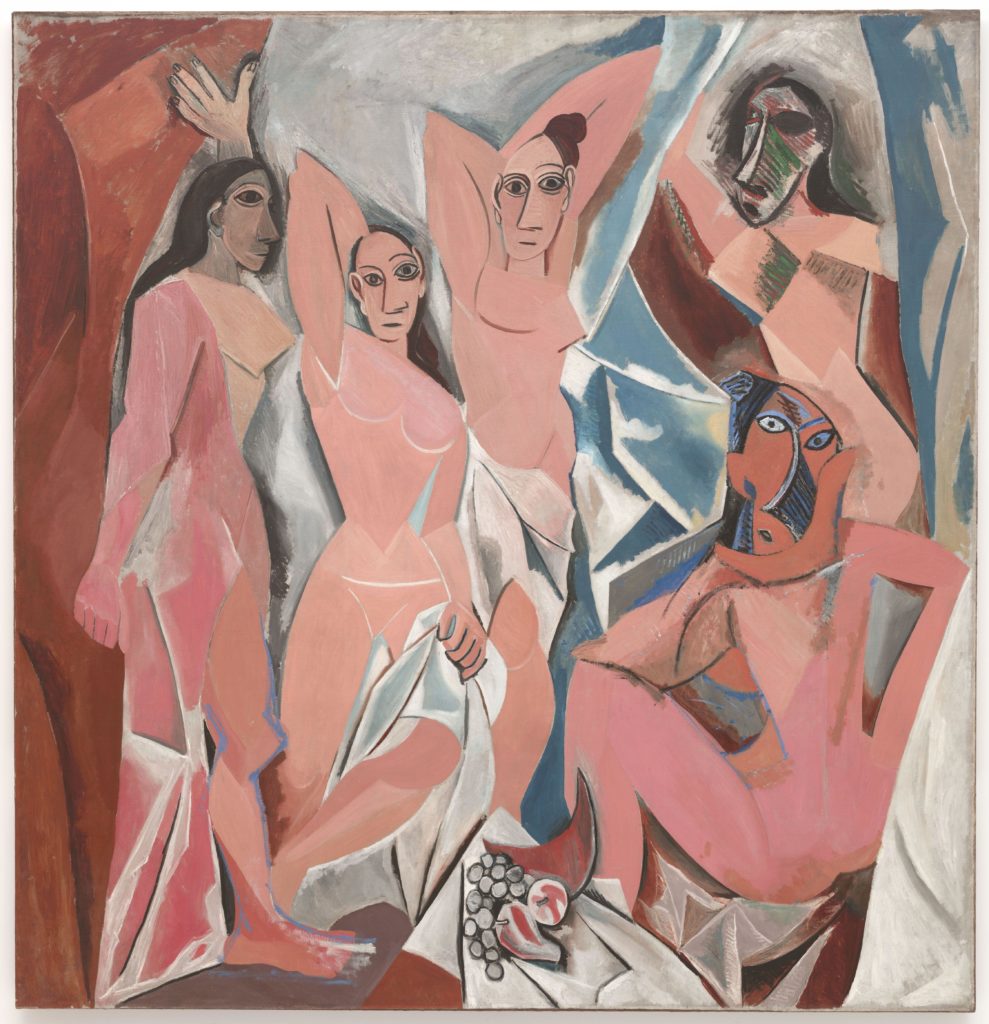

Primitivism

Our second style, Primitivism, takes the Romantic focus on Nationalism and folk music to a new level. Composers, influenced both by national pride in the “folk” of their country and by Charles Darwin’s theories of evolution, focused on humanity as being more “natural,” and disengaged from the modern world’s inventions, trials, and tribulations. As with Impressionism, Primitivist composers utilized non-Western harmonies and scales, but were also preoccupied with driving rhythms and odd meters. Primitivist composers set their music to stories based on folk tales and imagined pre-history, such as in Igor Stravinsky’s ballet, The Rite of Spring, which depicts a series of pagan-inspired rituals and dances. Primitivism also provided new avenues for virtuosic writing, examples of which can be found in Bela Bartok’s piano piece Allegro barbaro. Allegro barbaro couples pentatonic and polytonal chords with a fast paced forward movement, and nearly constant eighth notes.

Our second style, Primitivism, takes the Romantic focus on Nationalism and folk music to a new level. Composers, influenced both by national pride in the “folk” of their country and by Charles Darwin’s theories of evolution, focused on humanity as being more “natural,” and disengaged from the modern world’s inventions, trials, and tribulations. As with Impressionism, Primitivist composers utilized non-Western harmonies and scales, but were also preoccupied with driving rhythms and odd meters. Primitivist composers set their music to stories based on folk tales and imagined pre-history, such as in Igor Stravinsky’s ballet, The Rite of Spring, which depicts a series of pagan-inspired rituals and dances. Primitivism also provided new avenues for virtuosic writing, examples of which can be found in Bela Bartok’s piano piece Allegro barbaro. Allegro barbaro couples pentatonic and polytonal chords with a fast paced forward movement, and nearly constant eighth notes.

Neoclassicism

In contrast to Impressionism and Primitivism, the composers of the Neoclassical movement rejected Romanticism by looking back to music of the 17th and 18th centuries. Neoclassical composers returned to Baroque genres like the suite, concerto, and fugue, and utilized forms like the sonata form, minuet, and rondo with modern and even Jazz-influenced harmonies. These musical forms were not an outgrowth of the music of the time, but instead, were objects out of time, meant to provoke thought. Neoclassical sound experiments tended to include smaller ensembles with a greater emphasis on wind instruments than in previous time periods. Igor Stravinsky’s Neoclassical period was ushered in with his composition of the ballet suite Pulcinella, based on music from the 18th century. The ballet centers on the character of Pulcinella, an Italian commedia dell’arte figure, and the costumes and set were designed by Pablo Picasso. The original melodies, currently believed to have been composed by Domenico Gallo, were revised by Stravinsky for a chamber orchestra, and featured a heavy emphasis on wind solo instruments, with modern rhythms and harmonies.

In contrast to Impressionism and Primitivism, the composers of the Neoclassical movement rejected Romanticism by looking back to music of the 17th and 18th centuries. Neoclassical composers returned to Baroque genres like the suite, concerto, and fugue, and utilized forms like the sonata form, minuet, and rondo with modern and even Jazz-influenced harmonies. These musical forms were not an outgrowth of the music of the time, but instead, were objects out of time, meant to provoke thought. Neoclassical sound experiments tended to include smaller ensembles with a greater emphasis on wind instruments than in previous time periods. Igor Stravinsky’s Neoclassical period was ushered in with his composition of the ballet suite Pulcinella, based on music from the 18th century. The ballet centers on the character of Pulcinella, an Italian commedia dell’arte figure, and the costumes and set were designed by Pablo Picasso. The original melodies, currently believed to have been composed by Domenico Gallo, were revised by Stravinsky for a chamber orchestra, and featured a heavy emphasis on wind solo instruments, with modern rhythms and harmonies.

Atonality

The final style we’re going to cover is arguably the one most discussed within music circles: atonality. In connection with the artistic movement of Expressionism, atonal composers believed that music had gone as far as it could with regards to functional harmony, and that dissonance had to be emancipated--freed from the harmonic conventions of the past. As a result of this philosophy, music no longer had to sound consonant by following the rules codified by Rameau. Composer Arnold Schoenberg began experimenting with a form of atonality called serialism in the 1920s. In serialism, all twelve pitches of a chromatic scale had to sound before any could repeat. The belief was that this made all twelve pitches equal. To construct melodies, a composer would map out a matrix of all twelve pitches and base the melodies and harmonies on what was laid out in that matrix.

Tone Row Matrix for Arnold Schoenberg’s Piano Suite Op. 25

| I-0 ↓ | ||||||||||||

| P-0→ | E | F | G | D-flat | G-flat | E-flat | A-flat | D | B | C | A | B-flat |

| E-flat | E | G-flat | C | F | D | G | D-flat | B-flat | B | A-flat | A | |

| D-flat | D | E | B-flat | E-flat | C | F | B | A-flat | A | G-flat | G | |

| G | A-flat | B-flat | E | A | G-flat | B | F | D | E-flat | C | D-flat | |

| D | E-flat | F | B | E | D-flat | G-flat | C | A | B-flat | G | A-flat | |

| F | G-flat | A-flat | D | G | E | A | E-flat | C | D-flat | B-flat | B | |

| C | D-flat | E-flat | A | D | B | E | B-flat | G | A-flat | F | G-flat | |

| G-flat | G | A | E-flat | A-flat | F | B-flat | E | D-flat | D | B | C | |

| A | B-flat | C | G-flat | B | A-flat | D-flat | G | E | F | D | E-flat | |

| A-flat | A | B | F | B-flat | G | C | G-flat | E-flat | E | D-flat | D | |

| C-flat | C | D | A-flat | D-flat | B-flat | E-flat | A | G-flat | G | E | F | |

| B-flat | B | D-flat | G | C | A | D | A-flat | F | G-flat | E-flat | E |

Schoenberg’s method proved hugely influential for an entire generation of composers, including his proteges, the Austrian composers Alban Berg and Anton Webern.

Conclusion

While each of these styles are described separately here, many Modernist composers would mix and match elements within single pieces, and as well as across their entire careers. Some pieces would include “primitive” rhythms coupled with atonal harmonies nested within a Neoclassical structure. Composers like Igor Stravinsky and Aaron Copland experimented across a myriad of these styles throughout their careers. The musical experimentalism of the first half of the twentieth century exploded in the second half of the century, relying ever more heavily on new technologies and structural procedures for composing music.

Check out this list of major Modern composers to learn more:

Bela Bartok (1881-1945), Marion Bauer (1882-1955), Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924), Alban Berg (1885-1935), Lili Boulanger (1893-1918), Henry Cowell (1897-1965), Claude Debussy (1862-1918), Paul Hindemith (1895-1963), Gustav Holst (1874-1934), Arthur Honegger (1892-1955), Charles Ives (1874-1954), Scott Joplin (1868-1917), Gustav Mahler (1860-1911), Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992), Darius Milhaud (1892-1963), Florence Price (1899-1953), Maurice Ravel (1875-1937), Eric Satie (1866-1925), Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951), Alexander Scriabin (1872-1915), Ruth Crawford Seeger (1901-1953), William Grant Still (1895-1978), Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975), Richard Strauss (1864-1949), Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971), Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937), Germaine Tailleferre (1892-1983), Edgar Varese (1883-1965), Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958), Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887-1959), and Anton Webern (1883-1945)

And here are some musical examples to help you explore the sounds of Romanticism:

Musical Examples from this Period

Germaine Tailleferre’s Piano Concerto no. 1

Florence Price’s Symphony No. 1 in E minor

Igor Stravinsky’s Pulcinella Suite “Overture”

Prokofiev Symphony No. 1 “Classical”

Schoenberg Op. 23 no. 1 “Sehr Langsam”

Ruth Crawford Seeger’s “movement 4 Allegro Possible” String Quartet 1931

Henry Cowell’s The Tides of Manaunaun

Anton Webern’s Five Pieces for Orchestra Op. 10

Charles Ives “Putnam’s Camp, Redding, Connecticut” from Three Places in New England

Claude Debussy’s Prelude de l’apres midi d’un faune

Maurice Ravel “Menuet” from Le Tombeau de Couperin

Thanks for reading! Keep an eye out for more articles on music history, and for our Composer Bios article series, where we will survey the lives and music of your favorite classical composers.