It’s International Women’s Day 2018 and the 2017/2018 news cycle has contained a lot of bleak headlines.

There’ve been increasingly tense international political conflicts, massive natural disasters, and the threat of rolling back rights for women and the LGBTQIA community. With the rise of the #MeToo movement, vast numbers of women and men have come forward, exposing systemic sexual harassment and discrimination, causing entire industries to be re-evaluated for how they conduct business.

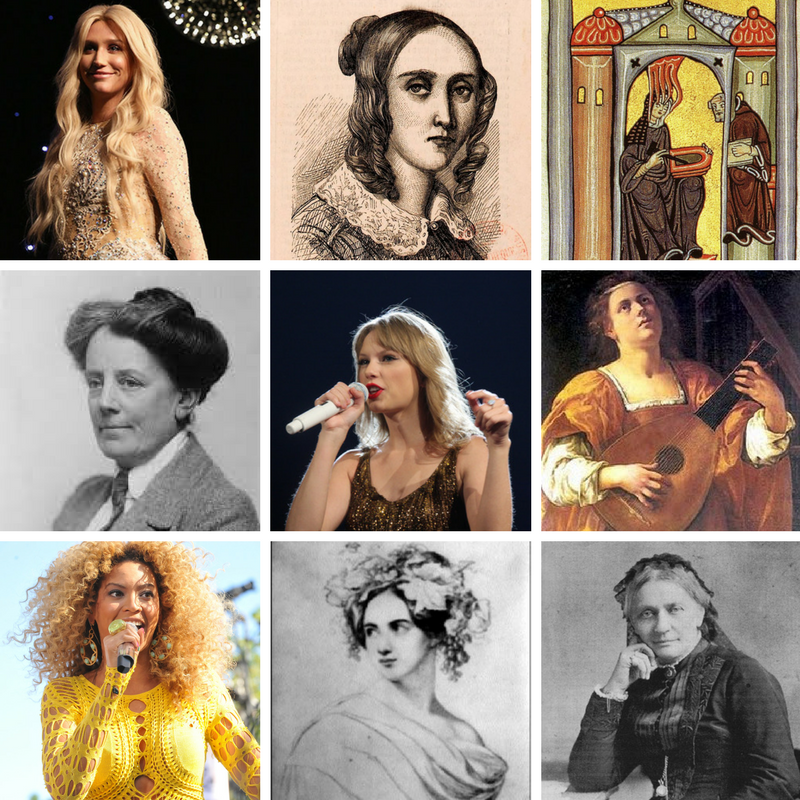

So, to celebrate this year’s International Women’s Day, we discuss obstacles that women face in creating music and tell some fascinating stories from the lives of women musicians who have been successful, ending with three of this past year’s most talked about artists: Beyoncé, Taylor Swift, and Kesha, and a short list of women composers whose works you should add to your repertoire.

International Women’s Day

International Women’s Day is the perfect cultural moment to address this issue; but, what is International Women’s Day?

International Women’s Day is celebrated every year across the world—as a part of Women’s History Month in March—to recognize women’s social, economic, cultural, political, and historic achievements.

The first Women’s Day was declared in 1909 in the United States, following strikes by female factory workers. These women were striking to protest terrible working conditions, unfair pay, and the lack of workers’ rights. (To read more about these strikes and the horrific 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Fire in New York City which helped spur on the Women’s Movement, and the fight for the right to vote, read this article.) Now supported by the United Nations, Women’s Day is an international celebration and call to action to continue working for women’s rights across the world.

The women seeking professional careers as musicians faced (and to an extent, still face) similar barriers to the women workers who went on strike in New York in 1908 and 1909 that sparked the first Women’s Day celebrations. In order to be a professional musician, women had to overcome social expectations, be educated in music, have time to create, have encouragement for creative work, and to have performances, recordings, or publications of her music.

Career Obstacles

Social Expectations

Though the degree varied depending on century and location, in general, society expected women to be devoted to their home, family, and religion.

Even in the nineteenth century, the ideal model of femininity was the “True” woman, who married, stayed at home, raised her children, and acted as a moral guide for the family. These women could perform privately and even compose simple music, but performing for profit or writing in complicated forms like fugues or symphonies undermined their femininity and the social status of the family.

So, to be a professional female musician, you either had to be a nun and perform music only for your religion, be born into a family of musicians whose reputation you would not jeopardize, or risk your familial reputation and be seen as a “bad” and rebellious woman.

Because of the work of the women’s movement fighting for equality and the vote—like the strikers above, and later feminist movements—these social expectations have lessened significantly; however female actresses and musicians are still frequently judged harshly in the media for choices regarding marriage, divorce, parenting, and not staying at home to raise their children.

Educational Opportunities

Opportunities to obtain a music education matched the societal expectations for women.

Historically, most professional women musicians were educated through the church or by family members and personal connections to those who were already professional musicians. For those with disposable incomes, private tutors were hired to teach their daughters music, as a part of their general education, but it was not expected that they become professional musicians.

Finally, at the end of the nineteenth century, more and more opportunities opened up for professional women musicians and educational institutions followed suit and offered opportunities to women and many women enrolled.

Time to Create & Encouragement

In addition, because the expected societal role of women was attached to the church or the family, women musicians needed time to create and encouragement.

Daily household management, raising children, and religious services took up a considerable amount of time. Frequently, the women musicians who were successful had help in these areas. For example, women who did not marry or whose families were wealthy enough to hire servants to take care of household duties and childcare had much more time available to spend creating music. With modern living and men taking up more household responsibility, women today do have more time to create than their foremothers.

On top of time, receiving encouragement is also highly influential to how seriously women pursue music careers.

Acceptance by Society

Finally, for a woman to have a successful career in music, she needs to be accepted by society, even though she usually bucked the typical social role laid out for her.

This acceptance comes in the form of performances and publication of her music and inclusion in histories or textbooks. Many women were able to get some support and encouragement for their endeavors, they were able to get their music performed, and even published! Yet, the women composers that came before are hardly remembered by later generations.

When looking at how audiences of the different periods received the women composers and wrote about them, one common theme pervades: each woman was touted as the “first” great woman composer and then forgotten about shortly before or after her death. Repeat ad libitum for each one.

Music history books are working to change this, and since the 1980s, hundreds of women composers that have long been forgotten are now remembered, though there are many more that still need to be found.

Overcoming the Obstacles

Though frequently ignored, music history teems with extraordinary women musicians who persevered against difficult conditions which frequently prevented them from having successful careers in music and control over their music. The following section discusses the above barriers in the lives of three women composers: Hildegard of Bingen, Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel, and Clara Schumann.

Hildegard of Bingen

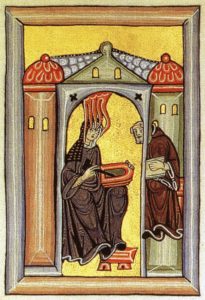

Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179), a nun from the Middle Ages, is one of the most famous women composers in all of music history.

Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179), a nun from the Middle Ages, is one of the most famous women composers in all of music history.

The tenth child of a noble family in Germany, Hildegard, like many other children of the time, was tithed to the Catholic Church. The Church was one of the few places in Europe to receive an education during the Middle Ages; and many monasteries and convents were places of great learning and music making.

Here, Hildegard was educated and eventually founded her own convent at Bingen (hence her name)! Hildegard, in particular, is known for her visions from God. These visions made Hildegard an influential person in Medieval Europe whose opinion on important matters was sought by emperors, kings, popes, and bishops. Hildegard recorded her visions, as well as religious poems, prophecies, and music and the convent preserved them for posterity.

The picture above depicts Hildegard receiving her visions and writing them down. Hildegard’s music, as was the tradition at the time, was only a melodic line to accompany the poetry, but their beauty is striking. Listen to“Columba aspexit” to hear the wide range and leaps in the voice.

Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel

Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel (1804–1847), sister to Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847), was educated alongside her brother in music, first by their mother, and then by private tutors.

Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel (1804–1847), sister to Felix Mendelssohn (1809–1847), was educated alongside her brother in music, first by their mother, and then by private tutors.

Hensel’s training was every bit as rigorous and thorough as her brother’s, yet he was encouraged to pursue a career in music and she was not. Instead, Hensel hosted private concerts in her Berlin home which housed a large music room with enough room for up to two hundred people.

In this music room, Hensel performed her own works on the piano and invited some of the best musicians from around Europe to perform, including Franz Liszt (1811–1886) and Clara Schumann (1819–1896; also a composer!) I recommend listening to Hensel’s Piano Trio, Op. 11, one of Hensel’s compositions that would have certainly been performed with Hensel herself at the piano during these concerts in her home.

Fanny Hensel, with her wealthy background and support from a close family and servants, had more time available to her to create music. She also received encouragement in her composing from her mother, brother, and husband.

Near the end of her life, her mother and husband encouraged Hensel to publish her works. Some of Hensel’s works were published under her brother’s name, and others, finally with her brother’s permission as head of the family, were published under her own name. In fact, in 1842, when Felix Mendelssohn was accompanying Queen Victoria in the performance of a collection of his songs, Victoria praised one of “his” songs, “Italian,” and Felix admitted to the queen that his sister had composed the piece!

On the other hand, Hildegard, who was a part of the Catholic Church, had a busy schedule. In addition to her daily activities as a nun, there was the daily (sung) performance of the Mass as well as the eight different Divine Offices—nine music services to be performed, every day. So, in Hildegard’s case, there might not have been much time to create, but there was a huge demand for music and it was a large part of her daily life, requiring her to make time to create music.

Clara Schumann

In contrast, Clara Schumann (1819–1896), virtuosa pianist and composer and the wife of composer and music critic Robert Schumann, had no women composer role models, felt a lack of encouragement for her compositional endeavors, and devoted much of her time to supporting Robert’s creative activities rather than her own. In 1839, in her shared diary with Robert (seven-hundred years after the life of Hildegard) she wrote:

a woman must not wish to compose—there never was one able to do it. Am I intended to be the one? It would be arrogant to believe that. . . . May Robert always create: that must always make me happy.

Path-Breaking Women Composers

The three women composers mentioned above are by no means the only women composers that there have ever been. Music historians have uncovered hundreds of women composers, each with their own paths to music careers full of trials, tribulations, and success. Their stories are unique and inspiring, and just a small snapshot into what their careers must have been like. Below, I include some outstanding stories from the lives of four women composers, Maddalena Casulana, Louise Farrenc, Ethel Smyth, and Chen Yi, before we move on to the three composers and performing artists Beyoncé, Taylor Swift, and Kesha.

Maddalena Casulana

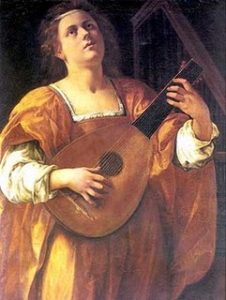

The first woman to be published, ever, was the composer Maddalena Casulana (ca. 1540–ca. 1590).

The first woman to be published, ever, was the composer Maddalena Casulana (ca. 1540–ca. 1590).

Casulana worked in Venice near the end of the Renaissance and wrote both sacred and secular madrigals (a popular vocal piece for one to eight voices where the composers express emotion and action in the music). She participated in intellectual groups and may have been a singer as well.

The dedication of Casulana’s first book of madrigals shows her tenacity to get her music published as well as the stereotypical beliefs about women’s intellectual abilities and that music was considered to be an intellectual activity, suitable only for men. While attempting to be humble and downplaying her achievement—as was common in dedications—Casulana dedicates this book of madrigals to a female patron, Isabella de’ Medici, well-known for her patronage of the arts and support of female artists. The first half the dedication starts strong with:

I know truly, most Illustrious and Most Excellent Lady, that these first fruits of mine cannot, because of their weakness, produce the effect that I would like, which would be, other than to give Your Excellence some proof of my devotion, to show also to the world (as much as is allowed me in this musical profession) the conceited error of men. They believe so strongly to be the masters of the high gifts of the intellect that, in their opinion, these gifts cannot likewise be shared by Women. Nevertheless, I did not want to fail to publish them: I hope these works will acquire so much light from the renowned name of Your Excellence (to whom I reverently dedicate them) that from this light other, more elevated minds may be kindled . . . .

I suggest listening to Casulana’s “Morir non può il mio cuore” from her second book of madrigals.

Louise Farrenc

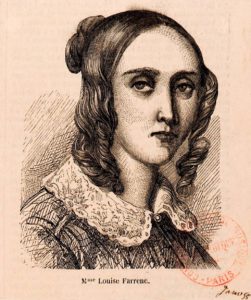

A close contemporary of Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel whose symphonies were positively reviewed by Robert Schumann, was the French composer, pianist, music historian, and pedagogue, Louise Farrenc (1804–1875).

A close contemporary of Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel whose symphonies were positively reviewed by Robert Schumann, was the French composer, pianist, music historian, and pedagogue, Louise Farrenc (1804–1875).

Farrenc lived in Paris her entire life; she was educated at the Paris Sorbonne and taught at the Paris Conservatory. She wrote numerous piano works, chamber works, and three symphonies. In her teaching, Farrenc emphasized teaching the “old” masters like J.S. Bach, around the same time that Felix Mendelssohn was reviving J.S. Bach’s St. Mathew’s Passion in Berlin.

Louise Farrenc stands out here, not because she was an incredible piano teacher implementing pedagogy styles that would become standard or because she was writing music in large, complicated forms, all of which are great achievements; but Farrenc did something else, something women today still often times struggle to do, and that is she demanded equal pay from her employer for equal work to that of her male peers—and she received it! In 1850, she wrote to the director of the Paris Conservatory:

I dare hope, M. Director, that you will agree to fix my fees at the same level as these gentlemen, because, setting aside questions of self-interest, if I don’t receive the same incentive they do, one might think that I have not invested all the zeal and diligence necessary to fulfill the task which has been entrusted to me.

You may have actually heard Farrenc’s music already and not known it was by her! The melody from her Piano Quintet Op. 31 is the theme used for NPR’s All Things Considered.

Ethel Smyth

Dame Ethel Smyth (1858–1944) also wrote large scale works, including the first opera by a female composer to be performed at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York (the second and only other opera but a female composer to be performed at the Metropolitan Opera House was L’Amour de Loin by Kaija Saariaho in 2016!), and many of these works and took on a feminist viewpoint. Smyth was an English composer.

Dame Ethel Smyth (1858–1944) also wrote large scale works, including the first opera by a female composer to be performed at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York (the second and only other opera but a female composer to be performed at the Metropolitan Opera House was L’Amour de Loin by Kaija Saariaho in 2016!), and many of these works and took on a feminist viewpoint. Smyth was an English composer.

Her father was opposed to his daughter studying music and becoming a professional musician, but eventually Smyth won out, and left for Germany to study. While studying privately in Germany, Smyth moved socialized with the likes of Johannes Brahms Edward Grieg, Joseph Joachim, and Clara Schumann!

Upon Smyth’s return to England, she met Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader of the English Suffrage campaign and dedicated herself to the movement. For the suffragettes, Smyth wrote many works, including her March of the Women. During Smyth’s work with the suffragettes, she, along with many other women, was thrown in jail for her activist work. When a fellow musician, Sir Thomas Beecham visits her in jail, he records this entertaining account of her activities while incarcerated:

She was arrested, tried, convicted and sent to Holloway prison to reflect and, if possible, repent. Well, she neither reflected nor repented. She pursued a joyously rowdy line of activity. Accompanying her were about a dozen other suffragettes, for whom Ethel wrote a stirring march, ‘Song of Freedom[March of the Women]’ and on one occasion I went to see her. . . . on this particular occasion when I arrived, the warden of the prison, who was bubbling with laughter. He said, “Come into the quadrangle.” There were the ladies, a dozen ladies, marching up and down, singing hard. He pointed up to a window where Ethel appeared; she was leaning out, conducting with a toothbrush, also with immense vigour, and joining in the chorus of her own song.

2018 marks the 100-year anniversary for some women winning the right to vote in England, thanks to the suffragettes!

Chen Yi

Chen Yi (b. 1953) was the first woman to receive a master’s degree in composition from the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing, China, and since has received a doctorate in composition from Columbia University and has produced numerous orchestral, choral, and chamber works, as well as works solo instruments.

Chen Yi (b. 1953) was the first woman to receive a master’s degree in composition from the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing, China, and since has received a doctorate in composition from Columbia University and has produced numerous orchestral, choral, and chamber works, as well as works solo instruments.

In these compositions, Chen blends Chinese and Western musical styles to create a remarkable fusion. This fusion allows her to express her cultural background both of the Western music she loved and began learning at the age of three and folk music she learned as a part of the Cultural Revolution and while playing in the Beijing Opera Troupe Orchestra. About her experiences, Chen states:

During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), Western music was prohibited, and all schools were closed. I had to practice my violin and piano secretively with windows shut and curtains down, blankets inside the piano and a metal mute on the violin’s bridge at home. When I was fifteen, I was sent to the countryside to be “re-educated” with thousands of other middle school students. For about two years, my daily life was marked by forced labor. This daily existence of hardship brought me closer in understanding farmers and the earth. Through this difficult time, I learned the importance of education and civilization. Musically, the spirit in Mozart’s music encouraged me to overcome the hardship and hope for the future. When I was seventeen, I became the concertmaster of the Beijing Opera Troupe Orchestra in my home city Guangzhou. This experience provided me the opportunity to play in the orchestra and sample the revolutionary operas. Consequently, it was from these orchestral performing experiences that led me to compose music for orchestra during the next eight years. I became familiar with orchestral practice (from performing to composing), including Chinese traditional instrumental music, and the Beijing Opera.

I suggest listening to her 2015 Choral piece “Thinking of My Home.”

While many of these women were strong and made great inroads in the field of music, you may not have heard of all of them, or even one! Yet, they worked hard to perfect their music and to control their musical lives.

Many of today’s most popular artists also struggle to control their musical lives and public images.

According to James Dickerson’s Go, Girl, Go!: The Women’s Revolution in Music, from 1954 to 1995, 75% of the chart topping hits were by male artists. While things were looking up for women in the 1990s and early 2000s, this gender inequity in recording artists has continued. According to a report “Inclusion in the Recording Studio?” from the USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative, from 2012 to 2017, only 22.4% of chart-topping songs were by women performers and in 2017, this number dropped to 16.8%! Even today, in 2017/2018, women are much less likely to be songwriters, producers, and have charting topping hits than their male peers. The same study from USC Annenberg found that just “12.3 percent of songwriters of the 600 most popular songs of the last six years were women, while 2 percent of producers across 300 songs were female. For producers, this translates into a gender ratio of 49 males to every female.” However, some of today’s most popular female recording artists, such as Beyoncé, Taylor Swift, and now Kesha, do write and produce their own music—yet sadly, their numbers are limited.

Beyoncé

Beyoncé Knowles-Carter (b. 1981) is called Queen Bey for good reason; and with her 2013 album and single “***Flawless,” she aligned herself with the basic tenet of feminism: equal rights for men and women.

Beyoncé Knowles-Carter (b. 1981) is called Queen Bey for good reason; and with her 2013 album and single “***Flawless,” she aligned herself with the basic tenet of feminism: equal rights for men and women.

Beyoncé writes much of her own material, maintains directorial and creative control of her music videos, performances, and tours, rarely gives interviews, and since firing her father as her manager in 2011 and becoming her own manager, her creative powers have only grown.

Beyoncé’s forays into singing, dancing, and acting began with local talent show competitions in her hometown of Houston, Texas, where she frequently beat much older competitors. Girl’s Tyme, the first singing group Beyoncé was in, performed on Star Search in 1992, taking the runner-up spot, when Beyoncé was only twelve years old. The group, like the early part of Knowles’ career, was managed by her father, Michael Knowles.

After a few line-up changes, Girl’s Tyme became Destiny’s Child and landed a recorded deal with Columbia Records in 1997. Even at this early time in her career, Beyoncé was co-writing many of the songs released by Destiny’s Child. Many hits from these Destiny’s Child records were about strong, independent women supporting themselves and not putting up with cheating partners, such as “Say My Name,” “Independent Women, pt. 1,” and “Survivor.”

After her early success with Destiny’s Child, Beyoncé branched out with other projects, including appearing in films like Austin Powers in Goldmember, The Pink Panther, and Dreamgirls, starring in MTV’s update of Bizet’s opera with Carmen: A Hip Hopera while simultaneously launching her solo recording career. Continuing her success in Destiny’s Child, Beyoncé’s solo albums topped the charts and racked up twenty-one Grammy awards. Beyoncé’s two most recent albums, Beyoncé and Lemonade have both been visual albums—with each song has an accompanying video—essentially making each album a short film, created, directed, and produced by Beyoncé and her team.

Lemonade takes the concept of a visual album even further than Beyoncé by mixing sound clips of interviews, speeches, and poetry between the songs to create a narrative about her real-life drama with husband Jay-Z. In Lemonade, Beyoncé brings clips from Malcolm X, poetry from Somali-British poet Warsan Shire, and draws on the film styles of black women directors of Kasi Lemmons and Julie Dash. Read more about Beyoncé’s Lemonade in “Beyoncé’s ‘Lemonade’ Is a Revolutionary Work of Black Feminism” and “Beyoncé is Fighting the Patriarchy Through Pop Culture.”

Early in her career, Beyoncé resisted the label of “feminist,” but now she is using her career as a platform, in addition to entertaining, to help educate the public about feminism as well as other social issues, including Black Lives Matter. Beyoncé’s 2013 single “***Flawless” contains an excerpt from feminist writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichi’s TED Talk on feminism and provides a definition of feminism in an attempt to educate the public. Beyoncé explained that:

I put the definition of feminist in my song and on my tour, not for propaganda or to proclaim to the world that I’m a feminist, but to give clarity to the true meaning. I’m not really sure people know or understand what a feminist is, but it’s very simple. It’s someone who believes in equal rights for men and women. I don’t understand the negative connotation of the word, or why we should exclude the opposite sex.

Taylor Swift

Ten-time Grammy award winner and another one of today’s highest earning artists, Taylor Swift (b. 1989) maintains strict control over her public image.

Ten-time Grammy award winner and another one of today’s highest earning artists, Taylor Swift (b. 1989) maintains strict control over her public image.

Similar to Beyoncé and other female artists with the power to construct their image, like Lady Gaga (Haus of Gaga), Swift rigorously directs what appears on her social media accounts like Instagram, Tumblr, and Twitter, to her squad of celebrity friends, only giving interviews where Swift has final say in what gets published, and also remaking her appearance for each album she releases.

Swift regulates her public image so much so, that she has become known in some circles as a bit of a control freak. Taylor Swift is the whole package, putting a massive amount of time and thought into her music and public image; and being in control of her career has sure worked in her favor!

From a young age, Swift was driven to pursue a career in music and her family supported her. Swift began performing around her hometown of Wyomissing, Pennsylvania by the time she was 10, stating:

Every single weekend, I would go to festivals and fairs and karaoke contests—any place I could get up on stage. The cool thing is that my parents never pushed me. It’s always been [my] desire and love to do this. That’s what makes this so sweet. . . . If I had been pushed, if I didn’t love this, I would probably not have been able to get this far.

When Swift was thirteen, the family moved to Nashville, where Swift had a much better chance of starting a career. She signed her first development deal with RCA Records when she was only 13, which was followed by a publishing contract with Sony at age 14! These produced no actual recordings, but the ground was laid. In 2005, Swift recorded her first album, Taylor Swift, with Big Machine. Singles from the album, “Tim McGraw,” “Teardrops on My Guitar,” and “Should’ve Said No” were all chart-toppers. These songs on this cd were either co-written or written entirely by Swift, as are almost all of her songs, no small feat for a fifteen-year old.

Throughout Swift’s stellar career, she’s released seven albums, with music ranging from country, crossing over into pop, and most recently into hip-hop (with Swift rapping on her new album Reputation), and EDM. Not only is Swift a fierce performer, racking up hit songs and awards while maintaining firm control on her public image, she also gives back. In 2013, Swift began the $4 million Taylor Swift Education Center at the Country Music Hall of Fame. In an interview discussing her views on the importance of music education and why Swift wanted to create this center, she stated:

music education is really such an important part of my life. My life changed so completely when I discovered writing my own songs and playing guitar, and that can’t necessarily all be taught to you in school because there aren’t enough hours in the day.

Additionally, Taylor Swift has stood up for herself and other female artists.

This advocacy has come to light even more with the recent #MeToo movement. The 2017 Time magazine Person of the Year was actually multiple people, “The Silence Breakers,” and one of those silence breakers on the front page of the magazine was Taylor Swift. Swift was included because of her visibility as a star, support of other women in ongoing battles against sexual harassment, and her own accusation against a harasser and subsequent court case.

This advocacy has come to light even more with the recent #MeToo movement. The 2017 Time magazine Person of the Year was actually multiple people, “The Silence Breakers,” and one of those silence breakers on the front page of the magazine was Taylor Swift. Swift was included because of her visibility as a star, support of other women in ongoing battles against sexual harassment, and her own accusation against a harasser and subsequent court case.

While Swift was on tour, during a promotional interview and photoshoot with a radio station, one of the radio station DJs groped Swift, Swift reported him, he was fired, for which he sued her for $3 million because she got him fired, and then Swift countersued for $1. The judge ruled in Swift’s favor. About the incident, Swift felt it was necessary to speak up because:

I figured that if he would be brazen enough to assault me under these risky circumstances and high stakes, imagine what he might do to a vulnerable, young artist if given the chance.” She countered his claim in court to “serve as an example to other women who may resist publicly reliving similar outrageous and humiliating acts.

Swift’s most recent album, Reputation, addresses her reputation with her fans, the media, critics, “Shake-it-Off” style haters, and sworn enemies. The theme of her “big reputation,” “bad reputation” appears in multiple songs, including the singles “Look What You Made Me Do,” “End Game,” and “Delicate.” In “Look What You Made Me Do,” Swift explicitly shows her mediated image. At the end of the music video, we see a line of Taylor Swifts, each parroting the criticisms she’s received. “Look What You Made Me Do” is a reiteration of Swift’s control of her music and showing her audience behind the veil of how she constructs that image after her most recent West-Kardashian feud.

Swift’s most recent album, Reputation, addresses her reputation with her fans, the media, critics, “Shake-it-Off” style haters, and sworn enemies. The theme of her “big reputation,” “bad reputation” appears in multiple songs, including the singles “Look What You Made Me Do,” “End Game,” and “Delicate.” In “Look What You Made Me Do,” Swift explicitly shows her mediated image. At the end of the music video, we see a line of Taylor Swifts, each parroting the criticisms she’s received. “Look What You Made Me Do” is a reiteration of Swift’s control of her music and showing her audience behind the veil of how she constructs that image after her most recent West-Kardashian feud.

Kesha

A more recent addition to the ranks of female musicians taking control of her music and career is Kesha.

A more recent addition to the ranks of female musicians taking control of her music and career is Kesha.

Kesha Sebert (b. 1987) is currently in the midst of an ongoing legal battle for control of her music in a pre-#MeToo battle with her former producer who sexually assaulted and emotionally abused her.

Because of this abuse, Kesha sued to be free from her contract with this producer, and while she no longer has to work with him, the contract still exists. Because of this legal battle, beginning in 2014, Kesha did not release any new music until 2017.

With her most recent album, Rainbow, Kesha took back creative control of her life. Much like Beyoncé, Swift, and Gaga, Kesha wrote her own music for this album, and she states:

“This whole album, for me, really is a healing album.”

The songs on the album deal with moving on after trauma and forgiveness.

In the writing and production of the music, because of her past struggles, Kesha took the lead and worked with her collaborators to get a sound and construct an image of herself that she wanted to produce, rather than being dictated to. This is striking in comparison to her first two albums, about which Kesha speaks in an interview with the New York Times. Kesha stated that for this album she had to be the fun, party girl all the time, a one-dimensional character.

Her reaction was:

I was like, ‘I am fun, but I’m a lot of other things.’ But [he’s] like: ‘No, you’re fun. That’s all you are for your first record.’

Kesha has been supported by a large fan community in her fight and numerous female superstars have backed up Kesha as well, including Adele, Pink, Kelly Clarkson, and Taylor Swift--who donated $250,000 for Kesha’s legal fees.

One of the most memorable moments from the 2018 Grammy Award Show was Kesha’s heart-rending performance of her first single off of Rainbow, “Praying.” Headlines afterwards proclaimed “We Will Remember Kesha Long After We Forget the 2018 Grammys” and “Kesha’s ‘Praying’ is Grammys #MeToo Moment.”Actress and singer Janelle Monáe introduced Kesha’s performance, connecting the song to the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements, stating: “We come in peace, but we mean business.” Echoing the supportive community surrounding Kesha’s legal battles, in her Grammy performance, she was joined on stage singing by such strong female singers as Cyndi Lauper, Camila Cabello, Andra Day, Julia Michaels, Bebe Rexha, and the Resistance Revival Chorus. The song text proclaims her independence from her abuser and her love for herself.

“Learn to Let Go” takes an even more positive outlook of letting go of the trauma and moving on with her life, which is what Kesha achieves with this album. The song contains a positive message with a catchy beat. Many of the other songs, including “Rainbow,” “Hymn,” and “Old Flames” continue the positive and forward-looking spin to Kesha’s life.

The music on the album explores a variety of styles that have influenced Kesha throughout the years, including country with growing up in Nashville, classic rock, and pop. On Rainbow, Kesha collaborated with Ben Folds, Dolly Parton, and Eagles of Death Metal, to name just a few. Yet, because her contract has yet to be dissolved, her former producer will still benefit financially from the sales of her record. Read more about Kesha’s struggle and the creative work that went into making Rainbow in the Rolling Stone article “The Liberation of Kesha.”

Moving Forward

The above musicians are just a few of today’s popular female artists who are breaking down barriers and making music their way, and definitely not the first. Singers like Madonna, Tori Amos, and Janis Joplin worked in a similar fashion. The evidence shows that when these artists get a say in their music, they do quite well for themselves. Hopefully, many more will come, the obstacles will lessen, and singers like Beyoncé won’t have to put the definition of feminism in their music in order to promote equality.

The women included here have all achieved the extra-ordinary, and though a music career takes hard work and perseverance, these women prove it is worth it. Their music gives them an outlet for their creative impulses, the ability to share important messages with the world, the chance to tell stories, it provides an emotional and healing outlet, and a community of support like that Kesha received.

Now after you’ve read some about these fascinating women musicians and gotten more background about International Women’s Day, go out and listen to and make some music! Below is a list of notable women composers for your reference. Look up their amazing music and add it to your repertoire!

Short list of Women Composers of Music for Piano, Guitar, and Percussion that is published:

- Francesca Caccini (1587–1641)

- Elisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre (1665–1729)

- Anna Bon (1740–1767)

- Marianna von Martines (1744–1812)

- Louise Farrenc (1804–1875)

- Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel (1805–1847)

- Clara Schumann (1819–1896)

- Lili’uokalani (1838–1917)

- Clara Kathleen Rogers (1844–1931)

- Teresa Carreño (1853–1917)

- Cécile Chaminade (1857–1944)

- Amy Beach (1867–1944)

- Marion Bauer (1882–1955)

- Mana-Zucca (1885–1981)

- Florence Price (1887–1953)

- Germaine Tailleferre (1892–1983)

- Ruth Crawford Seeger (1901–1953)

- Louise Talma (1906–1996)

- Grażyna Bacewicz (1909–1969)

- Margaret Bonds (1913–1972)

- Ruth Schonthal (1924–2006)

- Sofia Gubaidulina (b. 1931)

- Yoko Ono (b. 1933)

- Katherine Hoover (b. 1937)

- Joan Tower (b. 1938)

- Ellen Taaffe Zwilich (b. 1939)

- Meredith Monk (b. 1942)

- Tania León (b. 1943)

- Gwyneth Walker (b. 1947)

- Shulamit Ran (b. 1949)

- Libby Larsen (b. 1950)

- Kaija Saariaho (b. 1952)

- Chen Yi (b. 1953)

- Rachel Portman (b. 1960)

- Unsuk Chin (b. 1961)

- Jennifer Higdon (b. 1962)

- Ingrid Stölzel (b. 1971)

Ready to learn music?

Start learning with our 30-day free trial! Try our music courses!

About Liberty Park Music

LPM is an online music school. We teach a variety of instruments and styles, including classical and jazz guitar, piano, drums, and music theory. We offer high-quality music lessons designed by accredited teachers from around the world. Our growing database of over 350 lessons come with many features—self-assessments, live chats, quizzes etc. Learn music with LPM, anytime, anywhere!