It should go without saying that as music students, a sizeable amount of the time we spend thinking about and, well, practising music will be done at or with our instruments.

After all, we’re practicing to be able to play, and it seems counterintuitive to practice playing without the “playing” part of the equation.

To that end, we’ll spend many hours of many days of many years generating sound with our instruments, ever intent on shaping it to our desired musical vision.

This is as it should be; no musician has ever achieved mastery with their instrument by not playing it.

And yet, the achievement of musical mastery is not exclusively a product of generating sound from our instruments. Have you ever heard a toddler “play” the piano? It may certainly qualify as generating sound; however, few would say it qualifies as musical mastery….

What’s missing from the playing of a toddler compared to the playing of an experienced musician?

First and foremost, of course, are the hours and hours that an experienced musician will have spent playing and practicing their instrument.

But there’s more to it than that.

Experienced musicians will often look for ways to continue the study and practice of their craft away from the instrument.

They will study the score on the bus or try to hear a piece in their heads while walking through the park.

They will imagine the motions of playing while away from the instrument and will seek ways to bolster their knowledge about the music they’re working on.

They will create a mental image of how they want a piece to sound and will work towards being able to pick apart and identify aspects of that piece from that mental image alone.

They will do huge amounts of listening, both to music that is similar to what they are working on and otherwise.

The experienced musicians understand that the most effective way to improve their skills is through saturation, and through constantly refreshing the desire to learn and concentrate on musical material.

They understand that there is a world of improvement to be found beyond the instrument, and that limiting oneself to instrumental practice alone is to short change the learning process, potentially relegating it to a series of routine motions and methods.

In this article, we’ll take a look at some ways to study and explore music away from your instrument. We’ll present some options on how to embrace some powerful new methods of practice that will mean taking your fingers off the instrument and putting your brain into overdrive.

Take a good look at the score above.

What can you tell about it using just your eyes and the knowledge you have about how music notation works?

You may not be able to hear the complete product in your head, but you can probably pick out individual elements and describe how they work.

You can probably figure out the rhythm and tap or clap it out.

You can recognize the dynamics and the key, as well as the time signature and tempo.

If you have a knowledge of chords, you can identify the larger chord structures, and if you can find a melodic line, you might be able to sing it aloud or in your head.

Now, take a second look at the score.

Try to spend at least a couple of seconds with each measure.

What kinds of details are revealing themselves to you that you might have missed the first time around?

What about that strange looking split notation?

What about those little micro-crescendos in measure three?

What about all of those slurs curving around notes that also have staccatos? What about that time signature change between measures 4 and 5?

So much of what we just identified is crucial to realizing this music with our instruments, but we discovered it all by studying the score away from our instruments.

This may seem trite or counterintuitive, but ask yourself: "What is my process for learning a new score when I bring it to my instrument?” Where do you start? What do you look for first, second, and third? Is there a process, or do you simply dive in to see where the musical tide takes you? At what point do you put your fingers to the keys and play?

For many musicians, no matter their level of experience, the answer to that last question is, “almost instantly.” We love to play our instruments, and that desire, that need to get our fingers going sooner rather than later is a wonderful urge that we never want to lose.

However.

When we focus on playing with such a singular and automated drive, we tend to pull our attention away from some of the details we should be infusing into our musicianship. We gloss over dynamics and accent markings; we make mistakes in reading notation that we then must go back and correct. We unnecessarily elongate the time it takes to learn a piece of music by sacrificing the attention we should be paying to the details of the score for the cathartic release of playing our instruments.

The score above, which comes from the first prelude of Debussy’s Préludes, Book 1, “Danseuss de Delphes,” contains many of the kinds of details that are commonly missed when we decide to take a piece straight to our instruments instead of focussing on it away from them. Even very advanced sight-readers would be hard-pressed to catch all of the nuances Debussy has crammed into this score on the first few reads. Most musicians will need to confirm their understanding of Debussy’s instructions multiple times before being confident of their final product.

All that said, the first opportunity many musicians miss when they immediately bring the score to their instruments is the big picture view of the score as a whole. Doing this at your kitchen table or in a comfy coffee shop chair instead of at your instrument lets you better assimilate a piece’s broad strokes and trajectory. It establishes a recognizable framework in your mind that will help you when you do bring the score to your instrument. This type of studying adds a subtle but important layer of familiarity to your relationship with the piece that will make shifting between gestures, phrases, and sections that much easier.

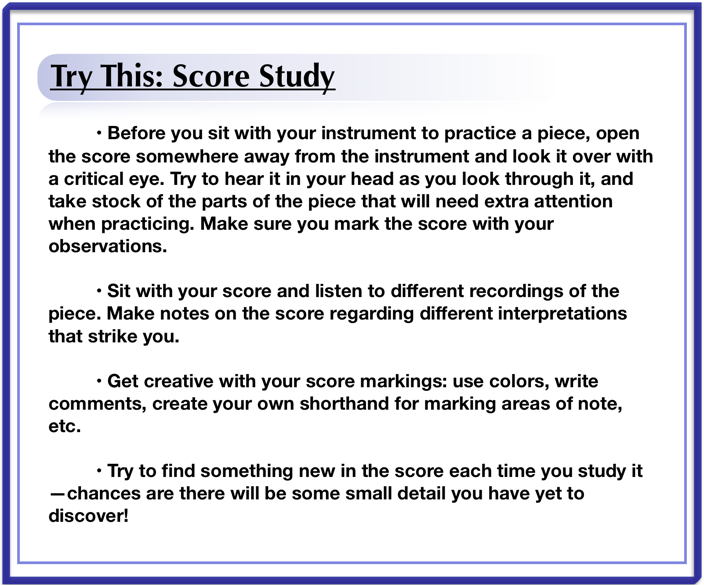

Looking at the score away from the instrument also affords you the ability to see, and, perhaps more importantly, to mark all of the important details on your score so that when you take it to your instrument you are easily able to see those details at a glance with the help of your own recognizable visual aids. In fact, marking up your score is one of the most effective methods you have for learning a piece quickly and completely, as it forces you to thoroughly peruse the notation and describe to yourself each marking.

Finally, especially for more complex works, you’re almost always going to find something new when you take an extra moment to look things over away from your instrument, even in a score with which you think you are plenty familiar. We tend to take for granted the presence of the music on the written page; however, it’s important to remember that the great composers infused their compositions with a musical depth and understanding the likes of which we can only hope to achieve in our lifetimes, and that it exists in the literature for us to seek out at every opportunity.

"Practicing" Away From Your Instrument

Check out the line in the example above. It’s not from any particular piece, but it’s similar to something you might see in any number of different musical styles.

Imagine that you’re sitting at your instrument. On the table next to your computer, see if you can “play” this line using the fingering and technique you would use if you were actually playing. Really think about which fingers you would be using, how your hand would be moving, and what the notes are that you’re playing.

Now go to your instrument and see if you can play it there.

Do you feel like working through the line on the tabletop made translating it to the instrument easier?

Whether your answer here was yes or no, there is a given fact about practicing music that we all share: We can’t always be sitting at our instrument practicing.

Without even mentioning all of the distractions and insistent demands of life in general, there are many reasons we can’t just sit or stand with our instruments and practice all day long. Physical fatigue, mental over-saturation, the need to eat… Not even conservatory students can quite manage a truly endless day of practicing (though many try). Such vast quantities of time spent with your instrument are generally not even healthy, and, outside of the well-monitored precincts of hardcore university settings, most of us should endeavor for a more moderate practice schedule in our lives anyway.

Fortunately, the fact that we’re not at our instruments putting fingers to keys need not be a deterrent for improving our musical skill-set throughout the day. In general, if you have time to think, you have time to practice, and there are many methods of improving your familiarity with the music you’re working on that you can pursue even when all you have available to you is your brain.

Before we start, we need to understand that the successful realization of a piece of music stems from a performer’s ability to blend their mental image of that piece with the physical choreography necessary to bring it to life with their instrument. Those are the two things we strive for when we practice: an excellent mental image and an excellent choreography. (Notice that we’re deliberately avoiding the word “perfect” here, as no music practice should live under the untenable pressure of that kind of goal.)

In understanding that our goals are an excellent mental image and an excellent instrumental choreography, we can start to pick out the facets of musical realization that cater to those goals. These would be things like: understanding and assimilating the notation, knowing how your hands will need to work to bring the notation to life with your instrument, and so on. We tend to do these things naturally over the course of the practicing process, however, if we’re talking about how we can take the practicing process away from the instrument, we need to know a bit more precisely about the goals we’re aiming for.

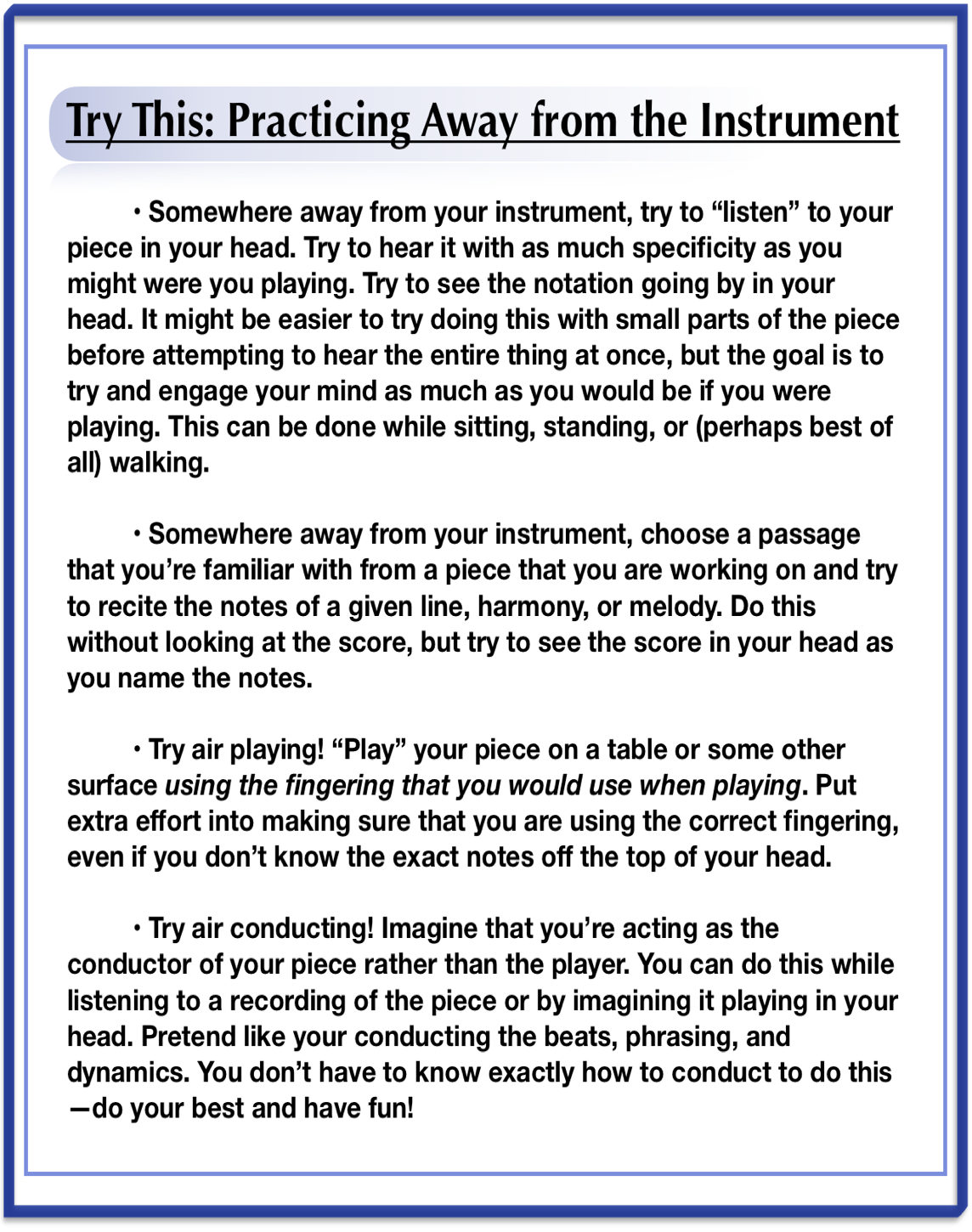

As you might have guessed, the method we started off with at the beginning of this article is targeting the “choreography” goal. This kind of “air playing” or “table-top playing” is most commonly found amongst professional classical musicians, but can easily benefit musicians of all kinds. The technique entails “playing” an accurate version of a piece of music (or, more likely, a small portion of a piece of music) on a flat surface or in the air. The trick here is to try and keep your fingering as precise as possible, which is more challenging than it sounds, even though the urge to tap along to music is fairly universal amongst musicians. How often do you find yourself tapping your fingers to a song you hear on the radio or while in a store somewhere? Think of this as a much more deliberate version of that simple and almost automatic habit. For many musicians, this is a great way to reinforce the knowledge of a line or passage while away from the instrument and it works many areas of musical internalization that are tremendously beneficial to the practicing process.

One of those beneficial areas that is necessary for “air playing” to work focuses on the other side of the goal coin—mental imaging. This is having a clear picture in your mind of the music notation and how the piece should sound when the notation is realized. This term is also used to refer to the finalized musical product a musician strives to generate in their head that serves as the ideal representation of the music.

Mental imaging can be fortified via a number of different practices. You can pick a passage of music to visualize in your head and try to go through naming all of the notes or chords. You can try to connect the mental image of the score in your head with an imagined audio version of it, which naturally helps to familiarize your brain with the sound/image connection. If you’re more familiar with the way a passage moves under your hands than you are with the identity of the notes themselves (which can happen in music with a lot of linear figures), you can “air play” the notes slowly with the correct fingering and name them as you go along.

The purpose of any of these exercises is two-fold. First, you will be constructively thinking about the music you’re working on even though you don’t have your instrument available to practice with. This is always good, no matter the context or method. Second, you will be forcing your brain to engage far more and in a different manner than it typically does when you simply sit down to practice. How many times has your teacher asked you to describe what something is at your instrument, only to have to tell you to use your words instead of your fingers because you instinctively tried to play the thing instead of describe it verbally? This type of brain engagement is at the heart of all of this—it’s a much more challenging, but also much more powerful type of learning. Once you can explain or describe a musical concept or technicality via non-musical means, you really know you have it.

So the next time you find yourself away from your instrument for an extended period of time, give a few of these exercises a shot. Even better, make the conscious decision to spend a few minutes of practice time you’d normally use at your instrument to do one of these instead!*

Listening

Stop.

Before you go any further, go and listen to a piece of music you’ve never heard before. It can be any style and any length, but don’t come back until you’ve given it a good listen.

Welcome back. How was your listening experience? Did you like the music? Did you dislike it? Did you choose something from a familiar genre or did you go wild and crazy and find something you’d probably never have listened to if you hadn’t been specifically asked to find something new? Is it something you would listen to again? Is it something you might like to play?

Whatever your answers to these questions, what you’ve just done, listening to a piece of music, ranks as one of the most important and underrated practices you can pursue away from your instrument.

No novelist can write without reading. No fine artist can paint or draw without studying copious amounts of imagery. No filmmaker can make a movie without watching lots and lots of other movies. And no musician has ever become great without the almost obsessive need to listen to music.

For many music students, the importance of listening to music rarely supersedes the perceived importance of practicing. This is not inherently bad; part of the nature of music as a performance art is that it requires consistent and, ideally, plentiful practice. Part of the beauty of music scores is that, if we follow their instructions well, they can give us most of the tools we need to passably bring their notation to life. However, scores can only do so much, and when we fail to consume enough music to accompany our practicing, we risk producing uninspired, stale, or inaccurate renditions. Without the knowledge of Classical Era music that comes from listening to lots of recordings, our Mozart can sound like Chopin, our Beethoven can sound like Liszt. Without listening, our ability to absorb the music and learn it efficiently can be stunted.

The flip side of listening to music that supports our practice habits is the great value of listening to different kinds of music. We live in an era when almost every conceivable type of music you can imagine is accessible with relatively little effort. For many musicians this is more of a curse than a blessing, as it can be challenging to stick to a certain specialization if all the genres and styles of music are calling out to be heard. But mostly it is a great boon of the modern era, and one which often goes under-utilized by many students of music.

The benefits of actively listening to a great and diverse volume of music is many-fold. We accrue information regarding styles and techniques. We learn to perceive the subtle differences between sub-genres and composer contemporaries (e.g., the differences between the early Romantic styles of Schubert and Schumann). We start to hear how very similar musical properties are used in the service of dramatically different sounding styles (such as how the same chord progression can be used in both classical pieces and an electronica songs). We subconsciously bolster our understanding of how music works and establish examples for how a finished piece of music should sound. And, who knows, we might discover new types of music to love that we never imagined we would.

In addition to active listening, we can also choose to pay added attention to the music that constantly surrounds us. Whether you’re watching a video online, hearing an ad come on in the middle of your favorite podcast, or walking through the supermarket, chances are you’ll encounter some sort of background or incidental music at multiple points throughout your day. Have you ever turned your attention to this music and really listened? It might seem a little ridiculous, but part of what we strive for as musicians is a sensitivity of listening that enables us to hear and focus on all types of music, incidental or otherwise. Even supermarket music is built using the same musical elements we encounter in more “serious” music. Might as well take the opportunity to practice some listening when we can!

Rounding Out Your Knowledge

Finally, there are many ways to improve your understanding of what it is you’re practicing by consuming information from ostensibly non-musical sources and by engaging in special musical experiences like going to concerts or communicating with other musicians.

For some people, going to concerts (or live music events in general) is second nature, and they strive to get out as much as they can. For others, the urge is not so strong, and it takes a little effort to get out to live music events. If you consider yourself a part of the latter category, remember this—practicing to play an instrument is, first and foremost, a performance art. This absolutely does not mean that you need to force yourself into a performance setting as a performer, but it is something that needs to be acknowledged whenever you consider why and how you practice. It also means that you could be missing out on some key musical experiences by not exposing yourself to the many factors that go into bringing a performance to life.

Consider the broad picture of how a performance is made reality. It all starts with the musicians practicing their music and building up a repertoire that can be used for a program or concert. Once that essentially significant part of the process is done, they need to somehow connect with and schedule a date at an appropriate venue. This can be as simple as one of the musicians knowing somebody willing to host a house concert, or complicated to the degree at which agents, promoters, and concert sponsors need to be involved. Then everybody needs to get to the venue for the concert. The musicians load in, the venue staff or band staff set up stage and sound, and then a soundcheck commences. After that there’s usually some sort of downtime for the musicians, who must entertain or otherwise occupy themselves until showtime. Showtime starts with “doors,” which is the time when the venue entrance is opened to the public, and then the actual showtime, when the musicians make their way to the stage to play. Music music music, applause applause applause (hopefully, anyway), and then the concert is done. Depending on the circumstances and the popularity of the musicians, what follows can be anything from audience greets, to autographing, to hiding in the green room until the venue has emptied out, at which point the musicians and the staff will break down the stage, load up into whatever vehicles are being used to transport, and move on to either dinner somewhere, the hotel they’re staying in for the night, or even onto the next city to get there in time to do it all again the next day.

As the audience for such performances, we only see a tiny sliver out of the middle of this whole process. As musicians though, knowing that this is the narrative going on behind the scenes can be quite enlightening when we consider that all of this is in service to the music. This is to say nothing of the opportunities we have to observe the performers executing their craft, how the music sound behaves in various venue spaces, and how the physical and human reality of live music can provide a very different experience from the stark “perfection” of recorded music.

So if getting out to concerts is not your forte, do yourself a favor, put in the extra effort every so often. Whether the performance ends up being sub-par or a wild success, the very fact of having opinions and thoughts on the matter will more than justify the expended energy.

In line with the social theme of concert-going is the interaction with other students of music. This can be especially challenging if you’re not in a collegiate setting or already a part of an established music scene in which musician interaction is common, however it’s nonetheless a very valuable effort towards improving your musical knowledge.

If you don’t already know any musicians, finding them can be a bit tricky. The key thing to remember is that the musical world really is a small one; if you can find and meet some of the musicians in a given city or region, you’ve probably got the start of a connection to most of the rest of them. Start by talking to your music teachers to see who they hang out with, and ask questions about how you can get yourself more involved in scenes or events that could result in you making more connections. You can also offer to volunteer for music events, look for community driven performance opportunities, or browse the online social media scene to see what sort of groups exist that you might be able to get involved with.

Lastly, always remember that you’ll never achieve the appreciation of another musician as reliably as you will by attending their shows. Support with your presence and your resources, and you’ll make fast friends!

Other things you can do to round out your musical knowledge and experience include reading composer biographies or histories of the eras from which your composer of choice hails, watching online videos of performances or of music related documentaries, or watching educational videos (such as the ones at Liberty Park!). You can also do some research into the workings and construction of your instrument. You might be surprised at how illuminating a little extra knowledge on how your instrument works can be!

Conclusion

With so much of our energies studying music spent dutifully practicing our instruments, it can be easy to ignore the many benefits of stepping back, taking our fingers off the keys, and immersing ourselves in practicing activities away from the instrument. Even a small amount of investment in such activities can work our musical minds in challenging and invigorating ways, and can dramatically increase our understanding and assimilation of the music we’re working on.

Remember, learning music is about viewing a relatively small group of essential elements from a vast number of angles. The more angles you can look from, the better you’ll get in a shorter amount of time.

Give these methods a shot! Embrace the diversity and depth of your musical experience beyond the boundaries of your day to day practice regime.