Cuban music can be broadly categorised into two groups: rumba and son.

As the names suggest, rumba styles share the rumba clave in common, whereas son styles make use of the less syncopated son clave.

Rumba is not one single style and the term is used to refer to three main subgenres (guaguancó, columbia, and yambú) all of which are Cuban musical styles of direct African descent. While these three subgenres are all classed as rumba, they are unique styles of music that must be approached as such. A similar parallel can be drawn with the term “pop,” which is a blanket word used to incorporate styles of music that are heard in the mainstream music charts.

One wouldn’t approach learning blues rock music in the same way that one would approach learning hip hop; both come under the blanket term of “pop” and both incorporate backbeat, but they are completely different styles.

This article will serve as an introduction to the genre of rumba as a whole.

While not going into a great amount of detail on each of the three individual sub-genres (that will be done in separate articles), we will introduce the key characteristics of each style as well as discussing the cultural roots that paved the way for the emergence of rumba music.

Background

The first African slaves arrived in Cuba in the early 16th century, though these early Afro-Cubans were small in number.

As sugar plantations grew exponentially in the 18th century, there was a greater demand for labour, so African slaves were transported to Cuba in much larger numbers than before to work the land. It was these slaves who would later develop rumba music, though it wasn’t until the late 19th century, facilitated by the abolishment of the slave trade that they were able to begin celebrating their musical heritage freely.

Rumba developed in the cabildos that could be found throughout Cuba. Cabildos were African guilds or fraternities designed to keep African language and culture alive. The African slave trade brought slaves from many different regions of Africa, and the cabildos offered slaves an opportunity to socialise with others from their specific culture and religion.

While music was undoubtedly played before the slave trade was abolished, the desire of the Spanish landowners to maintain Spanish cultural hegemony meant that such music could not be played freely, particularly as much of it was played as a form of prayer to African gods or deities.

For this reason, early rumba styles were played with makeshift percussion instruments (crates, boxes, machetes, sticks etc.) so they could be quickly disguised or hidden to pacify any suspecting hispanic Cubans. The cabildos played an important role in the development of different styles of rumba music. For example, members of the Abakuá cabildos had a common ancestry in Nigeria and Cameroon and the music they developed can be closely linked back to Nigerian and Cameroonian music.

Instruments

Specific instrumentation varies between different styles of rumba music (though many similarities are present) and as technology has advanced over the years, specific instruments have been adopted or dropped by rumberos (rumba musicians). Below is a list of some common rumba instruments.

1. Claves - Two small sticks which produce a sharp piercing tone that should be heard by the whole ensemble.

The claves play the same rhythm throughout the piece and the type of clave rhythm played dictates the patterns played by the rest of the ensemble.

In rumba music, claves are usually lower pitched than their son or salsa counterparts and one clave is often hollowed out to produce this lower pitch. Most traditional rumba pieces start with a single clave cycle before the rest of the band enters, similar to how a count in works in rock, pop, or jazz music.

2. Cajón - Translates to English as box or crate. These early rumba instruments were created from the boxes and crates used on the plantations to store and transport sugar or tobacco.

Cajones varied in size and pitch and different cajones had different roles in the ensemble. In most styles, some cajones were used to play a specific pattern while another cajon player plays a solo.

In the 1930s the cajon became less popular due to the invention of a new instrument that would change Cuban music forever.

3. Tumbadoras - The tumbadoras, or congas, are tall single headed hand drums that sit on the floor. They are made from hollowed out tree trunks or wooden staves and have a round controlled tone.

They became popular in the 1930s and effectively replaced the cajon as the main instrument used in a rumba ensemble.

Batá

4. Batá - While the double-headed bata drums aren’t traditionally used in rumba music (they are usually confined to worshippers of santeria, a religion practiced by Afro-Cubans of Yoruban origin), they have often been incorporated into rumba ensembles.

The first example of this is the group Afrocuba de Matanzas, who fused batá music with guaguanco and other rumba styles.

Shekeré

5. Shekeré - a large hollowed gourd covered in beads that’s shaken to create a deep, low-pitched shaker sound.

In rumba music, the shekeré usually outlines the first beat of each bar or phrase.

Catá

6. Catá - a piece of hollowed out tree that is struck with sticks to produce a soft woody clicking sound.

The catá player usually plays a rhythm that is closely related to the clave and has a similar function to the clave in that it repeats with little or no variation.

Millenium Cowbell 7

7. Campanas - Cowbells of varying sizes.

Not only does each rumba style incorporate bells of different sizes, the bells are also used in different ways. In mozambique (a style of music created by Pello el Afrokan), for example, the campana is used to play the clave rhythm, whereas in rumba columbia the campana is usually used to play a rhythm that compliments the clave.

Buy here

It’s important to remember that at its very foundation, rumba was all about making instruments from everyday items, and while the above instruments have become standard in rumba ensembles, it is possible to play rumba as it was played in its infancy to this day.

A good example of such music is demonstrated in the 2010 animated film Chico and Rita.

The whole film centres around a Cuban musician (Chico) and there is one scene in particular where we see a group of musicians in a Havana courtyard playing rumba. The clave rhythm isn’t played by a pair of claves, instead it’s played by an empty glass bottle.

Claves

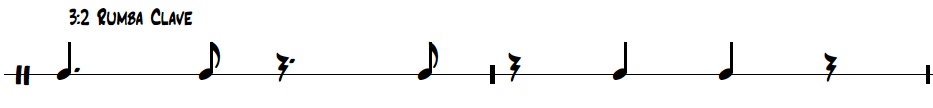

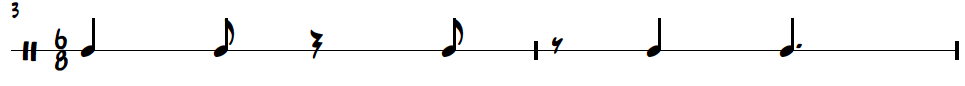

There are two main claves used in rumba music, the clave de rumba (rumba clave), and the clave de columbia (referred to in the West as the 6/8 clave).

The rumba clave is used in yambú and guaguancó, while as the name would suggest, the clave de columbia is used in rumba columbia. While the rumba clave is a simple rhythm (each beat is divided into 2 or 4) and the 6/8 clave is a compound rhythm, the two rhythms are very closely related. In fact when played at higher tempos it’s difficult to distinguish between the two.

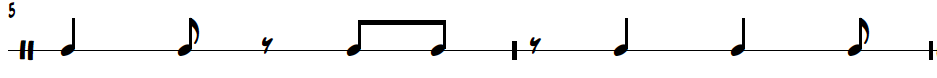

It’s common for the 6/8 clave to be varied like so:

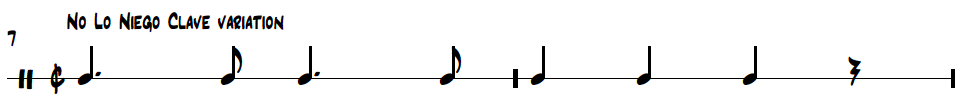

While it’s very uncommon for the rumba clave to be varied, this can also happen, usually towards the end of a song, and can be heard in a song called “No Lo Niego” by the famous rumba ensemble from Matanzas, Los Muñequitos de Matanzas.

Mid way through the song the clave starts to play the rhythm below.

Notation Complications

Rumba is a style of music that has been passed down through aural tradition and to this day, most rumberos learn aurally from more experienced musicians than themselves, without the use of Western notation.

Like many other folkloric styles of music that are also learned aurally, rumba presents many complications when being transcribed using Western classical notation.

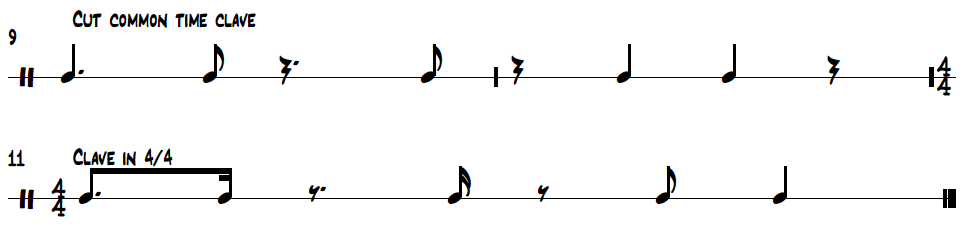

Firstly, there is no standardised method for notating it, so while some people notate clave in cut common time with 8th note subdivisions (figure A), others notate it in 4/4 with 16th note subdivisions (figure B.) There is no correct way of notating clave and rumberos in Cuba don’t tend to think of 8th/16th notes when playing the style.

This brings us onto the next complication when notating this style in the Western classical tradition.

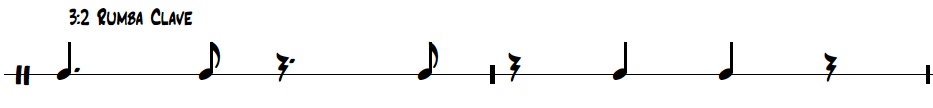

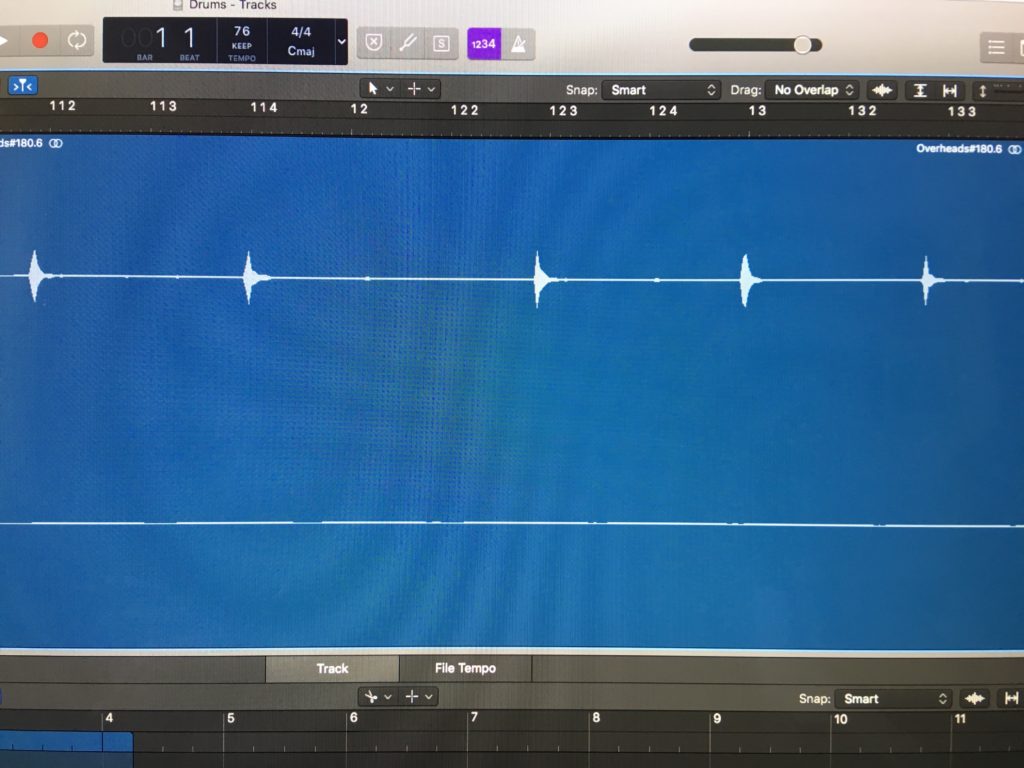

Similar to Brazilian samba music, rumba has a unique rhythmic inflection that doesn’t sit precisely within the Western Classical 8th/16th note rhythmic grid. If we examine how the 3:2 rumba clave is commonly notated, and compare it to an audio excerpt taken from the song “Rumba Pa’los Rumberos” by Los Muñequitos De Matanzas, we notice that there is a discrepancy between what is written and what we hear.

Specifically we can clearly hear that the final 3 notes of the rhythm are more evenly spaced than the notation would suggest.

This is only a very subtle discrepancy which is difficult to hear to the untrained ear, however it becomes clearer when we see the waveforms from this recording.

This not only presents a challenge in notating rumba music, but also in adapting it authentically to the drum kit. While it undoubtedly takes time to learn how to play the clave with an authentic rhythmic inflection, this becomes infinitely harder when trying to coordinate it with other rhythms (cascara, tumbao, etc.) on the drum kit. Be sure to keep this in mind when learning the style, but remember that the only way you will enable yourself to develop an authentic feel is by listening to as much rumba music as you possibly can.

We are blessed to live in an age in which folkloric musical styles are so readily available on streaming services such as Spotify or Apple Music, so make the most of the technology at your disposal and immerse yourself in this music.

Rumba on Drum Kit

Of course any style of music that consists of a large percussion section is difficult to play on a drum kit.

As a drummer playing rumba music your coordination will be pushed to its limits as you will be approximating rhythms played by a whole band with your four limbs.

What you play will of course depend on the musical situation in which you’re playing; are you the only percussion instrument? Is there a singer playing clave? Are you part of a large percussion section?

Below is a list of some common musical situations in which you might find yourself playing rumba or music derived from rumba.

Large percussion section:

- If you’re part of a large percussion section consisting of conga players you will probably only be approximating the clave, shekeré, and catá rhythms, with a bass drum pattern outlining the bass line if you’re playing with a bassist.

- It’s common in rumba music for one instrument to create solo phrases while the rest of the band plays a more rigid groove and in different subgenres a different instrument will take the role of the soloist.

- As a drummer you may also be tasked with playing such a solo. The fact that you’re playing rumba on drum kit is already an indication that you’re not playing strictly traditional rumba, this means that if you are tasked with soloing you can take certain liberties with how you solo.

- For instance, while in traditional rumba it’s usually just one instrument that solos, in this more contemporary rumba situation where you’re playing drum kit, you can probably solo using the whole kit, rather than one specific drum or cymbal.

Lone percussionist:

- If you’re playing in a small Latin jazz context with other non-percussive instruments, you will find that more is required of your coordination. As well as approximating the clave, catá and shekeré, you may have to play some conga rhythms.

- Remember that if you’re not playing traditional rumba, there’s no rule that says you have to include every rhythm present. Changes in texture can be a really interesting musical tool at the drummers disposal so if you’re playing more improvised music feel free to start thin and thicken out your sound as you go by adding more parts.

And here is a summary of how you can approximate these instruments on the drum kit, using sounds with similar tonal qualities:

- Clave: The clave can be played with the snare drum cross stick, or better still with a woodblock or a synthetic woodblock.

- Catá: The catá rhythms can be played on the rim of the snare or tomtom, or by striking the shell of the low tom. In more jazzy music, catá rhythms can also be played on the cymbals.

- Shekeré: The shekeré can be approximated with the hi-hat foot pedal. This is logical for drummers familiar with other styles because playing the hi-hat foot on the downbeats is something that we do in rock and pop music anyway.

- Congas: While I certainly prefer having an actual conga player, the congas can be approximated by playing the tom toms. More specifically the quinto can be approximated by the high tom, while the salidor/tumba can be played by the low tom and the tres golpes/conga can be played by the mid tom.

Conclusion

Rumba is a style of music that offers a unique challenge.

It’s incredible percussive density and rhythmic complexity make it a very difficult style of music to begin to play, while it’s unique rhythmic inflection make it even more difficult to master authentically.

Even though it has been adapted to the drum kit, it’s incredibly important to understand where these rhythms come from by studying rumba in its purest form.

While we will go into greater detail on each rumba subgenre in subsequent articles, it’s important that you start listening to as much music as you can to truly immerse yourself in the style.

Below is a list of important rumba bands, and bands who incorporate rumba into their music.

Listening List

Bands and musicians who play more traditional rumba music

- Los Muñequitos De Matanzas

- Clave Y Guaguanco

- Afrocuba de Matanzas

- Pancho Quinto

- Yoruba Andabo

- Los Papines

- Abbilona

Cuban bands and musicians who incorporate rumba in their music but also play other styles

- Afro Cuban All Stars

- Afro Cuban Jazz Project

- Los Van Van

- Irakere

- N.G La Banda

- Angá Diaz

- Mario Bauzá

- Chano Pozo

For an early example of rumba influencing jazz music listen to Dizzy Gillespie.

Ready to learn music?

Start learning with our 30-day free trial! Try our music courses!

About Liberty Park Music

LPM is an online music school. We teach a variety of instruments and styles, including classical and jazz guitar, piano, drums, and music theory. We offer high-quality music lessons designed by accredited teachers from around the world. Our growing database of over 350 lessons come with many features—self-assessments, live chats, quizzes etc. Learn music with LPM, anytime, anywhere!