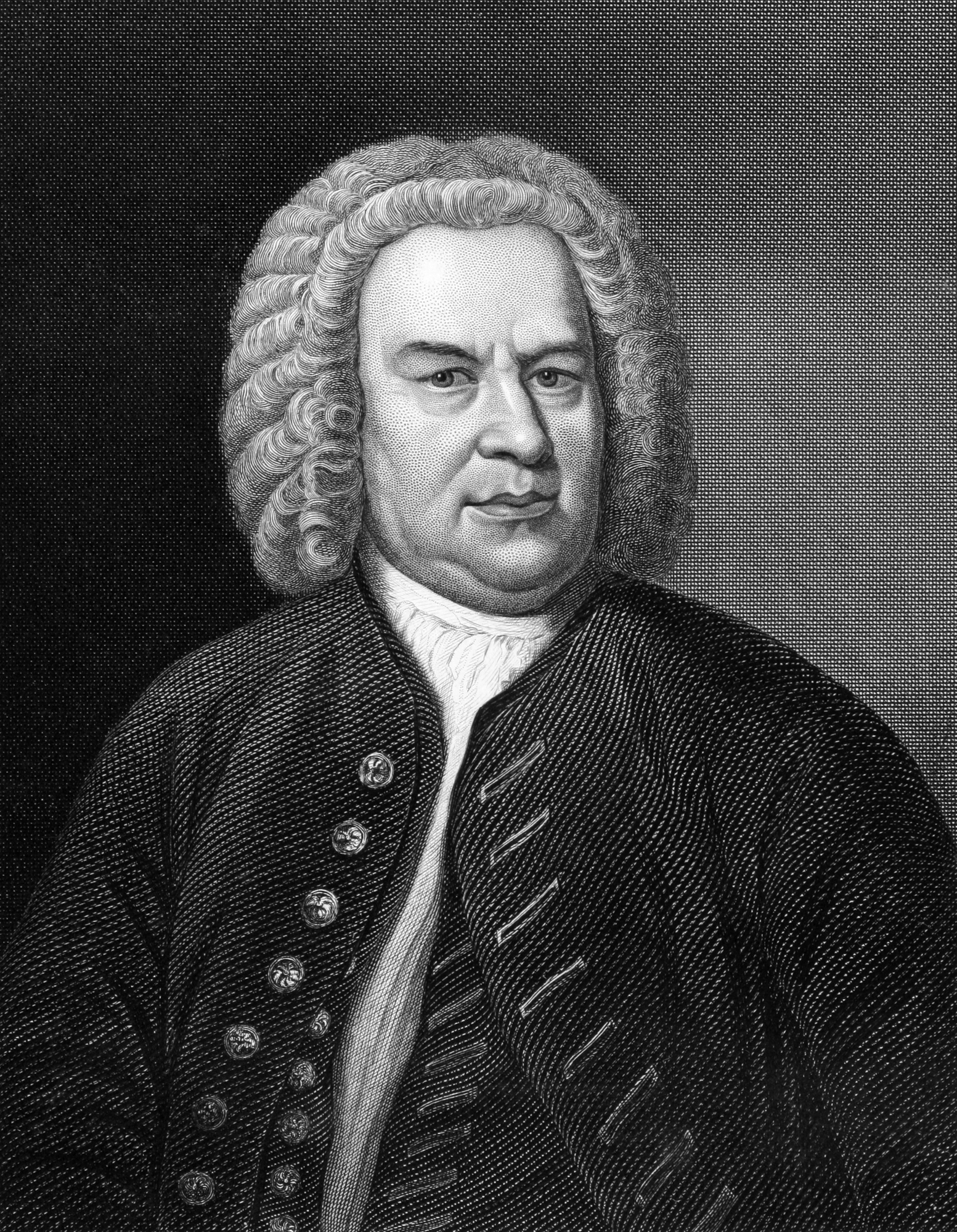

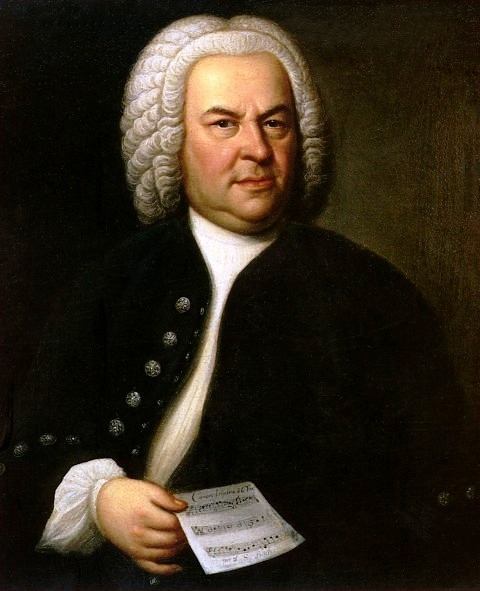

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) is one of the most famous composers of all time, and since his death, nearly all serious pianists have studied his works, which are seminal examples of the artistic style that was popular during the Baroque period. The Baroque period is known for its increased complexity and ornamentation in comparison to the artistic movements that preceded it.

In Bach’s case, he helped to expand upon and codify a number of musical concepts that are ubiquitous today, like modulation (moving from one key center to another key center) and counterpoint (multiple voices with their own individual melody line playing together to form a cohesive piece of music). Modulation on a keyboard was actually impossible before his time, because keyboards were tuned differently, and they were not able to play in all 12 keys and sound “good” like they can today. Our modern tuning system uses a technique called tempering to tune some or all of the pitches on a keyboard slightly out of tune in order to allow all of the pitches fit together.

Bach’s most famous keyboard works, the Well Tempered Clavier books, were written for the first modern keyboards tuned in this way.

For this reason, Bach’s keyboard works are excellent for practicing technical skills like fingering, arpeggios, and dynamics. For generations, pianists of all styles have studied Bach’s works to learn more about how to use the instrument to its fullest potential and how to develop their own musical ideas. If you are a pianist, you owe it to yourself to discover the musical secrets embedded in Bach’s work!

Many people don’t realize that the Bach family had many well known musicians and composers over multiple generations, including J.S. Bach’s own sons and his father. Back then, a professional musician usually worked for the church or local government in order to provide music for liturgical services and state events, although sometimes they were privately employed by wealthy patrons. These positions were incredibly competitive, and it is likely that the Bach household was practicing music day and night! Not only did musicians like the Bach family write music, they performed nearly every day and had their own private students. The compositions and musical documents left behind by the Bach family are of great importance to music history because of the family’s prominence. Among these documents are the two famous “Anna Magdalena Notebooks,” Bach’s two and three part Inventions that he wrote for his own students, and of course, The Well Tempered Clavier, two books that each that contain a paired Prelude and Fugue in every major and minor key. None of these collections were in print during Bach's lifetime. They have all been published posthumously, although they did exist as collections in the Bach household for their private practice.

Anna Magdalena was J.S. Bach’s second wife. The notebooks are comprised of handwritten transcriptions (copies) of music written by J.S. Bach and other composers of the time. Many of the transcriptions are in the handwriting of J.S. Bach himself, but other entries are made by Anna Magdalena, family friends, and J.S. Bach’s sons. The notebooks provide a good window into what music the Bach family was practicing and listening to at home, and likely assigning to their own private students. Some of these pieces have become quite famous today.

In addition to the Anna Magdalena Notebooks, another great source of Bach’s favorite practice exercises can be found in the works he wrote for his own students. Bach wrote a series of two and three part contrapuntal “Inventions” for his students to practice in all keys, arranged in ascending order starting from the key of C. So Inventions 1, 2, and 3 are C major, C minor, and D major, respectively.

In his own words, Bach described the collection as:

“Straightforward Instruction, in which amateurs of the keyboard, and especially the eager ones, are shown a clear way not only (1) of learning to play cleanly in two voices, but also, after further progress, (2) of dealing correctly and satisfactorily with three obligato [as written] parts; at the same time not only getting good inventiones, but developing the same satisfactorily, and above all arriving at a cantabile (singing) manner in playing, all the while acquiring a strong foretaste of composition.”

So, Bach wrote the collection of Inventions to teach his students not only how to play two and three voice counterpoint in a musical and non-robotic way, but also to demonstrate how to develop a short composition from a simple idea. An important thing to remember about this style of composition and instruction, is that many parts of the resulting compositions are not necessarily idiomatic to the piano. It takes practice and ingenuity to be able to play multiple difficult lines musically at the same time, so approach them slowly and methodically to be sure you are using the correct fingerings and gaining an understanding of the underlying musical idea.

I made this list of “Bach’s Favorite Practice Exercises” based on pieces that Bach wrote for his students and pieces the Bach family added to the Anna Magdalena Notebooks. Despite being centuries old, there is a lot for you to learn from a family of such master musicians!

1. Invention #4 in D Minor

This invention is built upon the musical themes outlined in the first four bars. The first two bars contain a melody in the right hand – known in this style as the “subject.” The next two bars have the same subject in the left hand, and the “counter-subject” in the right hand. Throughout the piece, these two musical ideas are developed, so be sure to look closely at how they are constructed and played before moving on!

The subject is an ascending and descending 16th-note line interrupted by a leap, and the countersubject is constructed of two 8th-note arpeggiated chords, in this case the i (Dm) and V7 (A7) chords. These elements are the materials that are used to construct the rest of the piece. You will notice measure 7 is the first instance of this style of construction occurring: the right hand “develops” upon the subject and the left hand “develops” upon the countersubject.

As you continue, it is helpful to be aware of some of the rules and their resultant patterns in this style of contrapuntal music. For example, parallel 5ths are considered ‘illegal’ in this style, and so the majority of voices that are moving in parallel motion (in the same direction) will be consonant 6ths and 3rds. You may also notice that each time the raised leading tone (7th scale degree) is reached from below, the 6th scale degree is raised as well. This is demonstrated in measure 42, when the B natural and C# “lead” up to the D. You have probably seen this pattern before in a scale book as the “Melodic Minor” scale, in this case it is from a D Melodic Minor scale.

Another important feature of this invention is in measure 27, when the piece modulates to the dominant key center, A. This modulation explains the resulting accidental markings of F# and G# throughout the section. It is very rare that an accidental marking does not have a harmonic or structural function in this contrapuntal style, so try to look for which key center the accidentals are “borrowed” from. This will help you to better understand the piece and allow you to fully utilize your knowledge of scales.

With all of the Bach Inventions, your practice list should include the following:

- Practice slowly

- Identify the subject and countersubject

- Identify key centers and scales

- Be aware of finger grouping and finger placement

2. Musette in D Major (Bach?) – From Anna Magdalena Notebook

This Musette was originally attributed to Bach by music scholars, but it has come into question whether or not Bach is actually the author. Regardless, this piece is featured in the Anna Magdalena Notebook, most likely as a useful practice piece. It is a good piece for a beginner to improve their reading and facility at the piano for a number of reasons.

The piece is only about a minute long and features two sections. It is most useful for beginners to become acquainted with two concepts: (1) playing both hands together in octaves and (2) using a left hand octave ostinato (repeated rhythmic accompaniment) to accompany a melody in the right hand. These two concepts are immediately demonstrated in the first four bars of the piece, as they sit side by side in contrast. You may find it useful to repeat only one of these patterns over and over (for example, repeat measures 1-2, then repeat measures 3-4) before putting both patterns together.

The Musette is in the key of D major and contains accidental markings, which helps to acquaint the student with multiple ways of reading and playing the black keys. The octaves doubled between the hands help to visually demonstrate where the same notes are on the page, and are a good example of how recognizing basic visual patterns like the distance between notes can reduce the number of individual notes a pianist has to read at one time.

3. Fugue in C Major - from Well Tempered Clavier and Anna Magdalena Notebooks

Fugue in C major is part of a collection of Preludes and Fugues written by J.S. Bach for all major and minor keys, and as such it is the first Fugue in the collection. The collection was written for students, but this Fugue was also transcribed separately in the Anna Magdalena Notebooks, which shows that the Bach family considered it a great practice piece on its own merit.

A fugue is piece of music with two or more voices that frequently repeats a singular musical idea or theme at different pitches through transposition. The Fugue in C major is built upon the theme outlined in measures 1 and 2. There are 4 separate voices in the Fugue, introduced one at a time in sequence from top voice to bottom voice throughout measures 1-6. Like the invention, there is a subject and countersubject that are transposed and used to construct the entire piece. The main difference between a fugue and an invention is one of complexity. A fugue is much more complicated, and often includes a modulation to the dominant key center (the key center a 5th above the tonic).

This piece is not for beginners! It is meant as an introduction for intermediate students to become acquainted with playing counterpoint in the fugue style. It is a piece that many pianists return to throughout the years to brush up on technique and to practice emphasizing individual voices. There are a number of sections that require careful finger placement and slow practice. We only have two hands, so in order to play 4-voice counterpoint, the patterns often boil down to two separate shapes. A good example of this is in measure 20, when the soprano voice rests, the alto, and tenor voices are covered by the right hand and the left hand plays the bass voice. It is important to be able to spot and emphasize the theme in order to bring out the separation between the voices.

4. Minuet in F major from Anna Magdalena Notebooks

The author of this Minuet in F major is unknown, but it was included by the Bach family in the Anna Magdalena Notebooks as a practice piece for new students and possibly as a sight reading exercise for more experienced players. It features a number of common techniques that must be mastered before one can move on to more advanced playing, such as playing in ¾ time, playing triplets, and repeating call and response patterns between the hands. The key of F, containing only one flat, is a good primer for students that only have previous experience in the key of C. Each hand only plays one note at a time, which allows beginning students to focus on technique and hand independence without being overwhelmed by reading. Measures 5-8 feature a common accompaniment pattern in the right hand in which the top note is repeated while the bottom note moves up and down. Finally, short modulation episodes introduce a few accidentals in order to keep the student on their toes.

5. Invention #8 in F major

This F major Invention is a little bit more advanced than the previously listed Invention in D minor, even though they have the same key signature. I’ve chosen to include this piece because, although it is not the most difficult of his Inventions, Bach seems to have written this invention specifically to test and improve his intermediate students’ technical capabilities. Before attempting this piece, students should be intimately familiar with the F major, C major, and Bb major scales, including being able to play them in contrary motion, which means being able to play the scale going up in one hand and while going down in the other hand. An important technical evaluation hidden in the piece is the 16th-note pattern in measures 4-7 and 26-29. In order to play a pattern like this, students must possess finger strength and dexterity (especially in the weakest finger, number 4) that can only be developed through regular practice!

The subject and countersubject in this invention are introduced in the first four bars. The subject is a rising arpeggiated F major chord, immediately followed by the countersubject, a falling sequence of 16th notes. Measure 5 sees the countersubject take over both hands and briefly modulate by introducing a B natural. All of these elements are developed throughout the piece, and so it is especially important for students to be able to identify each of them as they reoccur. In order to master this piece, you must practice slowly and deliberately in order to avoid turning small mistakes into bad habits. Try practicing the recurring patterns in each hand individually.

As an added challenge, see if you can transpose a pattern like the subject or countersubject to different keys not included in the piece!

Coda

These five pieces were undoubtedly important to the Bach family as practice exercises and teaching examples, but they are far from being the only useful pieces in the Bach repertoire. I encourage you to take a look at all of the Inventions Bach wrote for his students, as well as the entire catalog contained within the Anna Magdalena Notebooks and the Well Tempered Clavier. Use the skills you learned from analyzing and practicing these five pieces to identify how new pieces exhibit specific concepts that Bach and his family were interested in, like counterpoint, modulation, and technical performance. Finally, remember that these techniques are not limited to the style of Baroque music like that the Bach family is known for. These concepts can be applied to any kind of music! Jazz pianists, rock musicians, and folk artists and beyond have been studying and building upon the Bach legacy for generations. There is something new in their work to learn for everyone.

Now, it is your turn! Have fun!