Getting Started with Bach

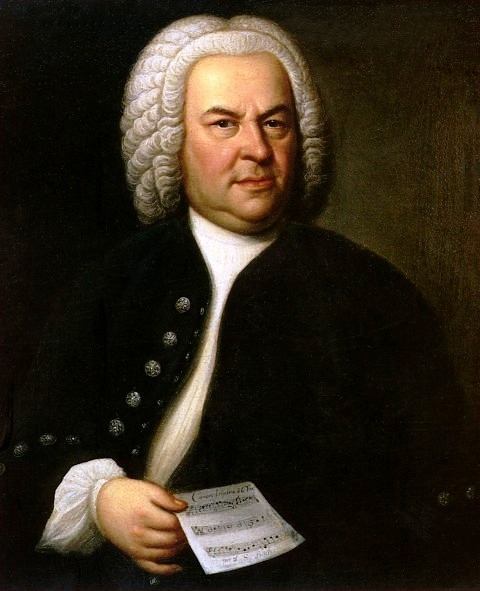

Few composers from history inspire awe and veneration quite like Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750). The ability to play Bach is a goal aspired to by players the world over. However, Bach’s work provides a unique challenge for budding keyboardists, due in large part to its use of a stylistic mode of compositional design known as counterpoint. A predominant feature of music during the historical period known as the Baroque Era (1600–1750), counterpoint treats each ‘line’ of music as an independent melody. The goal of the contrapuntal composer is to weave together multiple lines to create a cohesive musical whole. This is a different compositional principle than most of us are used to. Whereas much of the current beginner’s piano literature introduces music in terms of our familiar, basic music principles of ‘bass,’ ‘melody,’ and ‘harmony,’ music built using counterpoint (i.e., the music of Bach) requires that we combine these ‘multiple melodies’ together with our fingers. This makes it very important to pay extra attention to good fingering choices! In fact, for all the music that exists in the world, practicing Bach is still among the best ways to work on finger independence (and interdependence).

But where to begin? Here are six pieces to help get you started on the path to being a Bach player, complete with excerpts and explanations to help you navigate some key points, and YouTube links for some great renditions.

Happy practicing!

Minuets in G-major and G-minor, BWV Anh. 114-115

Oddly enough, two of the most well-known pieces new Bach players embark upon are not even attributed to Bach any more. These two minuets, featured in Bach’s famous household collection of small works dedicated to his second wife, Anna Magdalena, are actually thought to be the work of Christian Petzold, a contemporary of Bach’s. They do, however, share many of the features of Bach’s work, and provide a good introduction to not merely contrapuntal finger independence, but also some other technical needs commonly reserved for more advanced pieces in modern teaching music. These include the need to plan your fingering and finger grouping (which fingers you use on which keys so that you can more easily get to other keys), the need to smoothly span the octave, and the need to string sequential patterns into longer phrases.

(*Most of the works of Anna Magdalena’s Notebook make for great introduction pieces, so instead of going through all the wonderful options, I’ll just say, do the whole thing!)

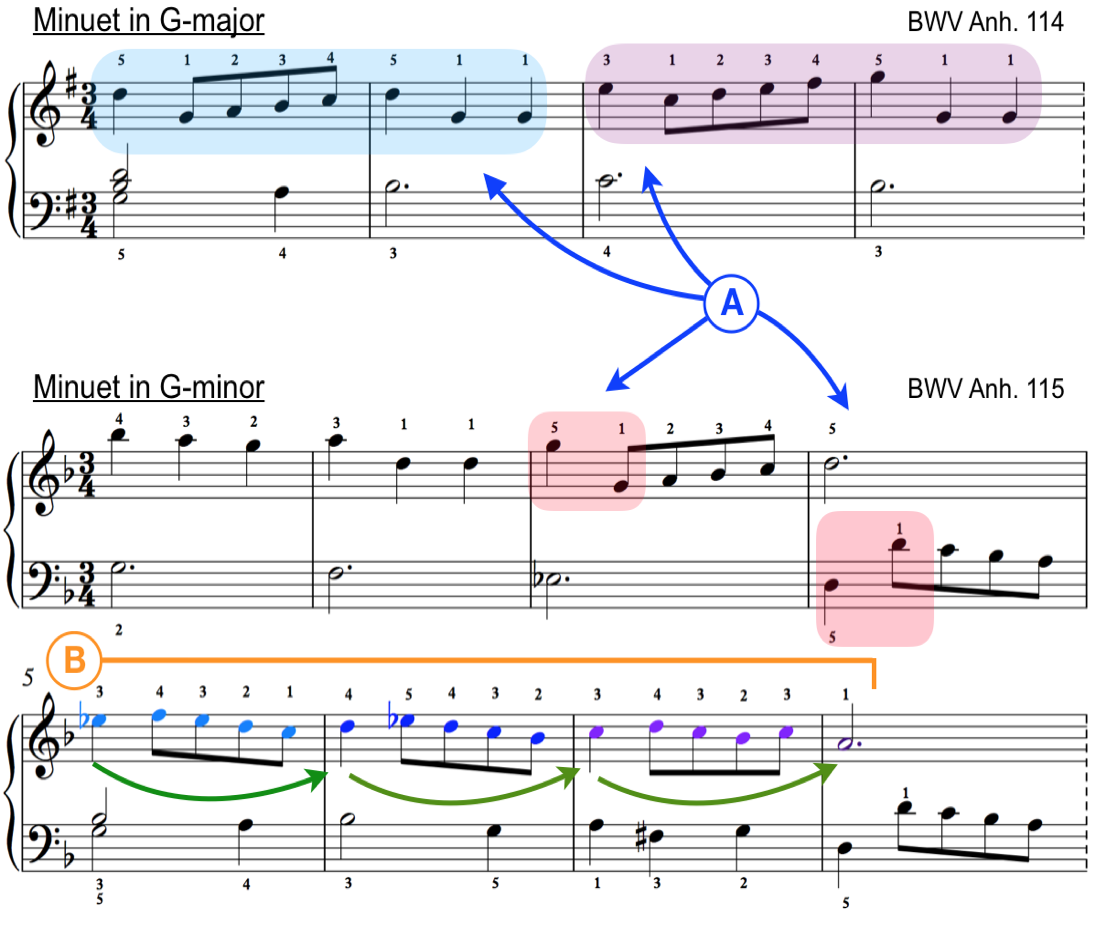

A: Both of these minuets provide opportunities to work on hand positions, finger groupings, and octave reaches. Notice how reaching from thumb (1) to middle finger (3) at the end of the second bar of the G-major Minuet allows the hand to easily adjust from the G-position of the first figure (blue margin) to the C-position of the send figure (purple margin). Below, in the G-minor Minuet, we see examples of octave-leaps taking us to new hand positions (red margins).

B: These Minuets are also a good introduction to Bach’s common practice of stringing similar ‘sequences’ of notes together up or down the scale. Instead of thinking of this as a passage of fifteen notes, try to think of it as three repetitions of the same figure (on m. 5, in light blue). Notice how the first note of every measure in the sequence is a step down from the previous (until the cadential leap at the end); try to think of these as the ‘core’ notes off of which you’ll develop your phrasing (green arrows), with the eighth-notes filling in between them.

G-major Minuet:

G-minor Minuet:

Remember, these pieces were actually written by Christian Pezold, however they are commonly associated with Bach and are great introductions to playing in Bach’s style

Prelude in C-major, Well-Tempered Clavier, Bk. 1, BWV 846

In a way, this most simple and beautiful of Bach preludes is also one of the most accessible and easy to learn. It relies on a mode of musical execution called ‘figuration,’ which refers to a pattern used to break up chords into little, musical figures (in this case, a rising, repeating arpeggio). The trick here is to think of each measure as a chord, instead of a bunch of notes, and to follow the line of chords as they move by one or two notes at a time. To get the real effect of this piece, think of the bass notes as drops of water in a pool, and the rising ‘figures’ as ripples coming out of each note.

This is the first piece of Bach’s incomparable masterwork for keyboard, The Well-Tempered Clavier, BWV 846-893 (also known as the WTC). As pianists in modern times, it is easy for us to take for granted that, unless it is out of tune, the piano will give us a similar set of sounds as long as we choose the same combination of keys up and down the keyboard. For example, a major chord sounds very similar whether the root of the chord is a C, E, F, Gb, etc., with the only difference being how high or low we’ve chosen to play it on the piano. This is possible through a system of tuning known as equal-temperament. Equal-temperament tuning allows for each half-step to be tuned to an equal ratio from the notes around it, which gives us the ability to translate sounds equivalently across all keys. This was not always the case! From before and throughout much of Bach’s life, instruments were tuned in ways that made some keys sound ‘extra’ good, at the expense of others sounding very strange. In using equal-temperament tuning, we make compromises with the ‘purity’ of some intervals so that all intervals sound approximately the same, which gives us access to play in all keys. While equal-temperament as we know it didn’t come into widespread use until somewhat after the Baroque era, the developments of tuning towards equal-temperament during Bach’s time allowed him to employ tuning systems of similar versatility. The importance of these developments for Bach is nowhere better represented than in the Well-Tempered Clavier, which was the first compendium of keyboard works to be featured in all 24 major and minor keys. Bach apparently enjoyed the challenge of writing in all keys so much that, 20 years after writing the first book of pieces in the early 1720s, he composed a second! The WTC is generally thought of as the combination of both books.

In addition to being the first full set of keyboard works in all keys, the WTC is a brilliant example of keyboard and counterpoint composition, and is considered standard literature for all serious pianists.

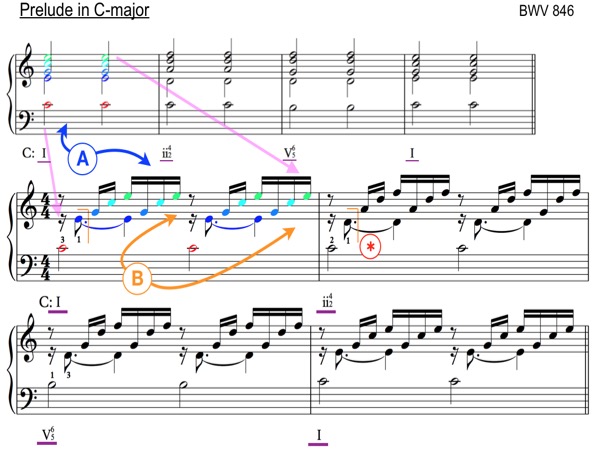

A: Look at these chords in the small staff above the main score excerpt. Can you see that they can be broken up and expanded to build the shapes we see in the piece (pink arrows)? This is called ‘figuration,’ and it is another common practice from the Baroque era. It is one of the easiest ways to make a basic harmonic idea (e.g., a series of chords) and make it musical by simply breaking up those chords into similar arpeggios. Almost every measure of this piece is built in this way, and it is often easier to identify which chord makes up each measure and to think of playing chords instead of linear figures.

B: In practicing this piece, try to think of the bass notes (in red) like stones tossed in a pond, out of which the succeeding notes radiate upward. A great exercise you can do is to try and vary the figuration of the upper notes. Try playing exactly the same notes, but after first playing the bass note, alter the order of the notes that come after. This way of taking an element of a piece and altering or playing with it can be an excellent learning tool! The different perspective will help deepen your knowledge of the piece, and reinforce the choices that were made in its composition.

*Notice these orange brackets; they indicate that you should be playing with a specific hand, and are usually seen when it may not be obvious which hand you should use to play a part of a passage. These particular brackets are telling you that both the bass note and the second note in the measure should be played with the left hand. This encourages smooth phrasing and ease of movement. Be aware, Bach did not write these in his manuscripts; they appear here and in other editions as publisher’s additions for the sake of the reader.

C-major Prelude, BWV 846:

Prelude in C-major from Five Preludes, BWV 939-943

Bach wrote a number of small preludes, many of them ostensibly meant for teaching. The process of learning music in Bach’s time was generally more comprehensive than it is in modern times. Even if students were not destined to become composers by profession, they were still required to pursue composition as part of their music studies, and to familiarize themselves with the compositional and improvisational practices of the day. Short pieces, such as this one, were supposed to help students build themselves up to more challenging works, and to learn concise, creative compositional choices and techniques to bring to their own compositions. Don’t let the string of 16th-notes at the end of this little prelude scare you, they fit very nicely under the hand, and are a good way to show off the scale work you’ve been doing! In fact, it’s a good idea to start practicing with that line first (with the metronome, of course), and then to continue on the rest of the piece based on a speed that’s comfortable for you once you get to it. What you want to avoid is starting the piece at a speed that makes those 16th-notes far too challenging to tackle once you get to them. Also, this piece is usually written with mordents (trills) on the 1st and 3rd beats of the alternating left hand octaves in bars 9-11; feel free to skip these until the core notes are easy for you.

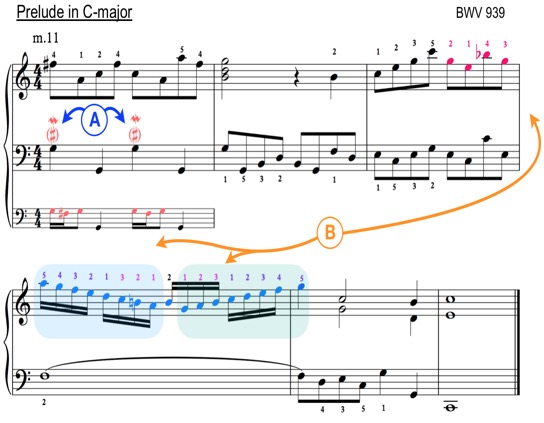

A: Ornamentation was a common practice in Bach’s time. Composers employed a variety of symbols to specify where they wanted ornamentation to take place. This ornament is called a ‘mordent,’ and it indicates that the player should play a short, rapid trill on the written note. The sharp in the parentheses below it (#) indicates the note neighboring our written note (the one we will be trilling with) should be sharped. Trills and mordents should be fluid, but should also happen in time. An example of how you might play this mordent is provided in the small (ossia) staff below the main measure (in red).

B: There are two parts to making this 16th-note run easier. First, we must approach it with good fingering so that we are in an optimal hand position (top right, in magenta). Second, we must recognize that the line is really made up of two scales (both of which are all white notes): one coming down from A to A (blue margin), and one going up from G to G (green margin). We have one note in between them that serves as a pivot point. Notice how the fingerings for the scales mirror each other. These are the same fingerings you use for the C-major scale, and this passage seems much easier if you’ve been practicing your scales and can think of it as two C scales starting and ending on A and G instead of a bunch of really fast notes. Use a metronome, and go slowly!

C-major Prelude, BWV 939:

Sarabande in A-minor from English Suite, II, BWV 807

A number of easier works can be found hiding in the generally more difficult English and French Dance Suites. This heartstring-puller of a sarabande (a slow, stately dance piece in triple meter, typically featured in a Baroque dance suite) features some particularly lovely harmony, and is a good exercise piece for creating smooth, slow, one-handed lines and legato parallel sixths and thirds. As an aside, this particular sarabande was discovered complete with a written out ornamentation from Bach himself, a rarity given that most ornamentation at the time was simply assumed, or marked via trill marks and other such symbols. Feel free to omit all ornamentation until the core notes of the piece have been mastered.

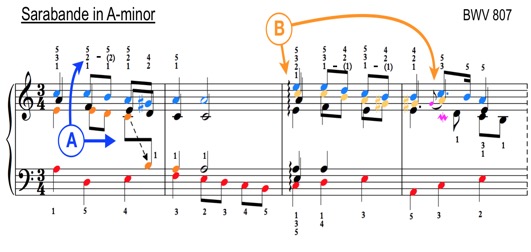

A: In a sarabande beauty contest, this one might take the gold, and it’s far easier than it looks. Don’t let all of those fingering numbers intimidate you! The stacked fingerings refer to the highest and lowest notes in the staves directly above or below them, and some fingerings have been separated for ease of viewing. The numbers with dashes in between them are notes that are held while those around them move. This is a good piece for working on your ability to create smooth lines with multiple notes in the same hand, which is a prevalent necessity in much of Bach’s music.

A good first step here would be to learn the bass and treble notes, being sure to play them with the same fingers you will use when you combine everything together. Next, using the right hand only for a moment, try to add the notes of the sixth and third intervals. (Notice at the end of the first measure where the lower note jumps down into the left hand. Use your left hand thumb here even though it might seem a bit strange at first.) Now, add the bass notes back. Finally, repeat the same thing (first the right hand alone and then adding back the left) with the remaining notes. Practice for cohesion and clarity; there are some lovely sounds in here, and they should be properly appreciated. You may use a small amount of pedal to help smooth the transition between harmonies.

B: As mentioned in previous examples, ‘ornamenting’ a piece of music was a common practice during Bach’s time. While composers would add symbols to specify the use of certain ornaments for certain moments (such as the ‘grace note’ and ‘mordent’ seen here), it was generally expected that a performer would do much more ornamenting than was written on the page. This sarabande is unique in that it was found with a separate, completely written out ornamentation, which now is almost always featured in published copies. Applying this ornamentation does make the piece more difficult, and thus, as with any ornamentation, should be reserved for when the piece has been learned first without.

Sarabande in A-minor, BWV 807:

(Note that the first and second parts of the piece repeat, and that during the repeats the pianist plays the written ornamentation.)

Invention in C-major, BWV 772

You won’t get far in your musical education before you start hearing about Bach’s vaunted Inventions and Sinfonias. These teaching pieces have doubled as standard repertoire for pianists the world over for centuries. They are short pieces, meant to introduce students to both the playing of and good composition practice of first two voices (Inventions), and then three (Sinfonias). You might wonder why these are not introduced as the first pieces one should learn going in to Bach, and the answer is that, despite their origins as pieces for education, they can actually be quite tricky, and the phrasing and technical prowess they demand is actually more for the intermediate pianist than the beginner. Fortunately, the C-major Invention is rather accessible, featuring easy finger grouping, clear phrasing, and gentle counterpoint. Try to notice all of the ways in which the opening line in the right hand is manipulated to generate most of the material in the piece; it is a common feature in Bach, and in much counterpoint-based composition.

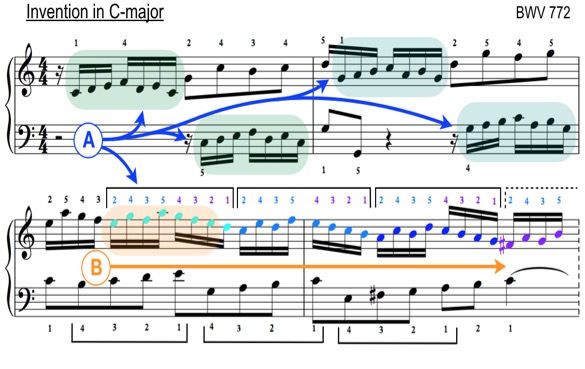

A: Counterpoint is a kind of composition in which the music is built by interweaving ‘lines’ of melodic material. Ideally, these lines will be both obviously related, and obviously independent. It is common in counterpoint to build pieces on the repeated ‘entrance’ of the same melody or line, and then to evolve the piece through the natural (but carefully constructed) development of these lines. You may have heard the word ‘canon’ before in reference to this style of composing, and Bach is often thought of as the ultimate master of ‘canonic’ writing. Bach’s Inventions are two-voice pieces (meaning they only use two independent lines of music throughout), Observe how the opening line (green margins) is used to construct the piece, entering first on C (in each voice) and then on G in the measure after. In a lot of contrapuntal writing (writing using counterpoint), this opening line will be repeated, broken up, and even turned upside down to generate musical material for the piece. Check out how it is presented backwards in the construction of this sequence (orange margin)!

B: As we learned earlier in the G-minor Minuet (BWV Anh. 115), Bach often employs ‘sequences’ in his works. Sequences are a tool by which composers can create movement in a piece, and can be identified by their tendency to repeat the same figure while moving up or down a scale or across a harmonic structure. Because they seem to move a lot, sequences can look a little scary, however they are almost always built with repeating notes and fingerings, and become much easier to think about once you figure out these elements.

In this sequence (starting with the teal notes, ending in purple), the note pattern corresponds to a pattern of fingerings (in brackets, above). The figures all occur within a standard five-fingered position, except for the crossover from thumb (1) to index finger (2) at the end of each repetition. A good way to practice would be to slowly play the first figure to the first note of the next (teal to light blue), and then to stop, let the hand relax on that note for a beat or two, then repeat. When you’re comfortable with that, add the next repetition in the sequence, and so on. Notice that the bass hand also has a sequential set of notes and fingerings. Once you have the sequence in the right hand, practice the left hand by itself, and then practice both by adding the bass note under the first note of each four-note group as you play through the sequence (e.g., C and E in the left hand with E and G in the right for the first figure). Go slowly (this is not a fast piece), and make sure to use the correct fingering!

Invention in C-major:

Coda

Few composers have had such a respected and lasting influence on the world of music as Bach. Translated from German, the name ‘Bach’ means ‘brook,’ or ‘stream,’ but of the man himself, Ludwig van Beethoven once wrote, ‘he should be called sea, not brook…’ Claude Debussy offers his own commentary, referring to Bach as, ‘a benevolent god to which all musicians should offer a prayer to defend themselves against mediocrity…’ And Johannes Brahms, in sagely instruction to all musicians stated, ‘Study Bach: there you will find everything.’

Many pianists maintain at least some Bach in their personal and professional repertoires throughout their lives. For others, the playing of Bach is a lifelong endeavor, and they pursue the mastery of Bach’s works with fervor and devotion. Whether you’re casual enthusiast or a professional devotee, the study and practice of Bach will undoubtedly improve the quality of your playing and understanding of music across all musical spectrums.

To continue with your Bach training, try your hand at some of the smaller Preludes from the same series as the C-major Prelude, BWV 939 featured here (BWV 940–943), the Three Minuets for Wilhelm Friedemann Bach (BWV 841–843), and almost any of the selections from the aforementioned Anna Magdalena’s Notebook. These pieces will continue some of the technical and stylistic lessons you’ve worked on here (care with fingering, phrasing, finger independence, the blending of lines, etc.), while providing you with alternative and gradually more challenging scenarios in which to employ your skills.

Remember when practicing to make sure you know your fingerings and hand positions, to break down your phrases and lines into more easily digestible chunks, and to use the metronome to help you manage your speed.

And enjoy!