At the beginning of practically any score of music you have ever looked at there are numbers and symbols that clarify how to interpret the music notation in the score. As a music learner, you’ve become familiar with these symbols and you know that the numbers tell you how to interpret the music’s rhythms, how to count and keep track of the beat, and that if you’re playing with other performers—the numbers help you stay together!

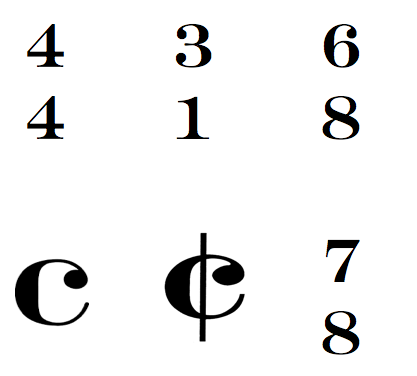

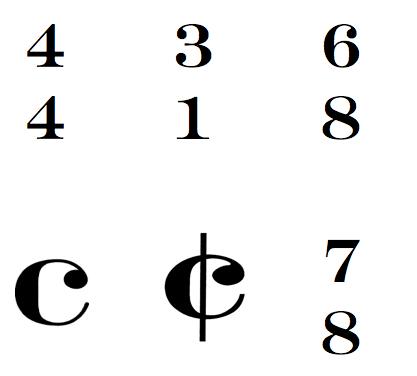

Yet, there are so many numbers and so many ways for these numbers to be written:

These are just some of the time signatures you might encounter. Notice also in the above image that there are time signatures in the form of letters instead of numbers, which adds even more possibilities and potential complications into the mix; however, these letters really just stand in for numbers with added special meanings.

All of these time signatures raise the questions: do we really need all of these different time signatures? Do they really mean different things? Why do composers and musicians prefer some time signatures over others? These time signatures really do have slightly different meanings and purposes in music, but some can sound the same to the ear. Some are quite rare and others are more common.

This article will explain the basics of reading time signatures and meters, show how the various time signatures are related to each other and can sound similar and different, and why composers might choose certain time signatures over others.

Sound in Time

Fundamental to the definition of music itself is that music must move through time—it is not static. Hence, music is sound organized through time. This organization of music through time is managed in the Western music system through time signatures.

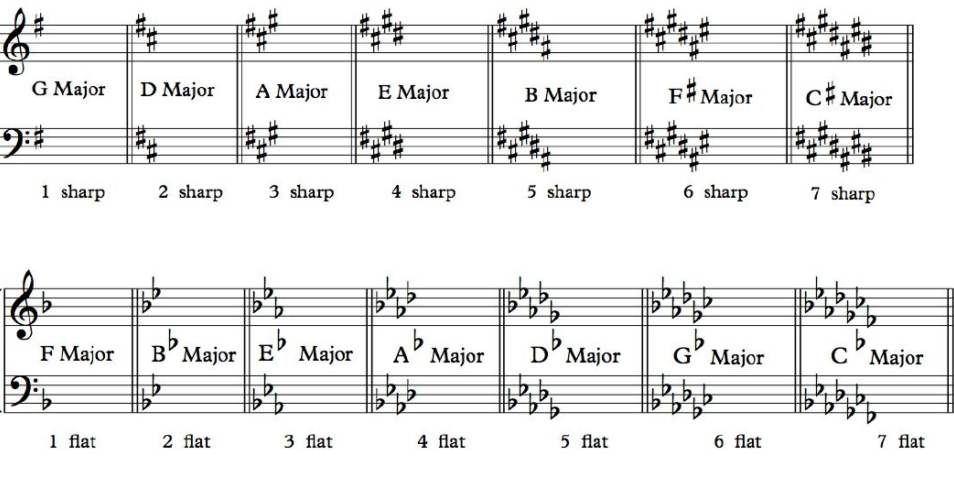

The time signatures give us a way to notate our music so that we can play the music from scores, hear its organizational patterns, and discuss it with a common terminology known to other musicians. The organizational patterns of beats, as indicated by the time signature, is how we hear and/or feel the meter of said piece. When discussing music, the terms "time signature" and "meter" are frequently used interchangeably; but time signature refers specifically to the number and types of notes in each measure of music, while meter refers to how those notes are grouped together in the music in a repeated pattern to create a cohesive sounding composition. The methods for classifying the various time signatures into meters is discussed in detail later in this article.

Meters vs. Rhythms

Meter is the comprehensive tool we used to discuss how music moves through time. That said, there is another way that musicians also discuss how music moves through time, and that is through rhythm. Rhythms are the lengths of the notes in the music itself - which notes are long and which notes are short. Musicians learn how to play these rhythms in the context of each piece by using the time signature.

The Notation

In musical scores, we organize the music into “bars” or measures. A “barline," or measure line, is where the five horizontal lines of a staff are intersected vertically with another line, indicating a separation:

Each measure has a specific number of notes allowed to be placed in it, and that number of notes is dependent upon the time signature.

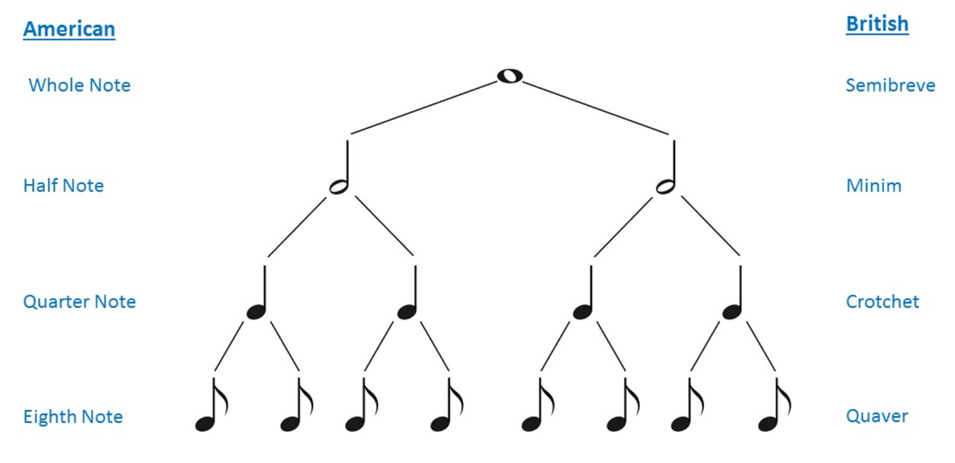

Notes

The most common notes which are used to make the short and long rhythms in the various meters are included in the chart below, beginning with the longest held notes and going to the shortest. This chart also mentions the length relationship between the note values.

As the notes in the various metric breakdowns get bigger or smaller, the equivalent relationships continue. For example, a double-whole note would last as long as eight quarter notes!

Reading the Time Signatures

The number of notes allowed in each measure is determined by the time signature. As you saw in the time signature examples above, each time signature has two numbers: a top number and a bottom number: 2/4 time, 3/4 time, 4/4 time, 3/8 time, 9/8 time, 4/2 time, 3/1 time, and so on.

The bottom number of the time signature indicates a certain kind of note used to count the beat, and the top note reveals how many beats are in each measure. If you look at the American note names from the chart above, there is a fun little trick to it:

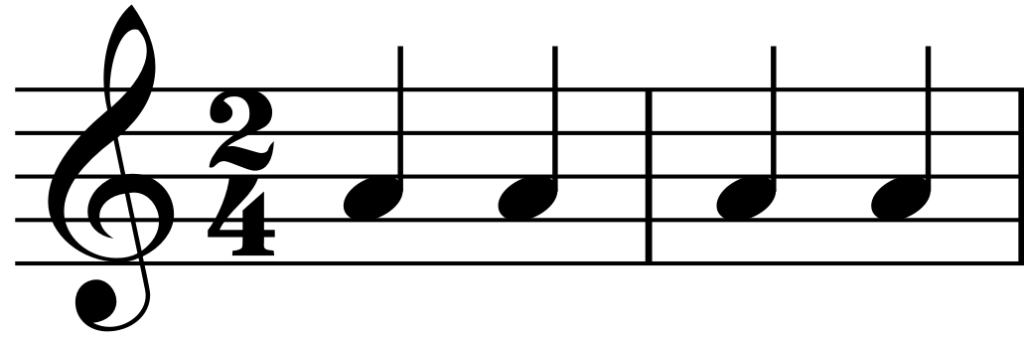

Take the 2/4 time signature for example - with the 2 on the top of the time signature you know there are 2 beats for one measure, and this leaves you with a fraction of 1/4—a quarter, the note-length the time signature is indicating to you then is a quarter note. Therefore, you know that there are two quarter notes worth of time in every measure:

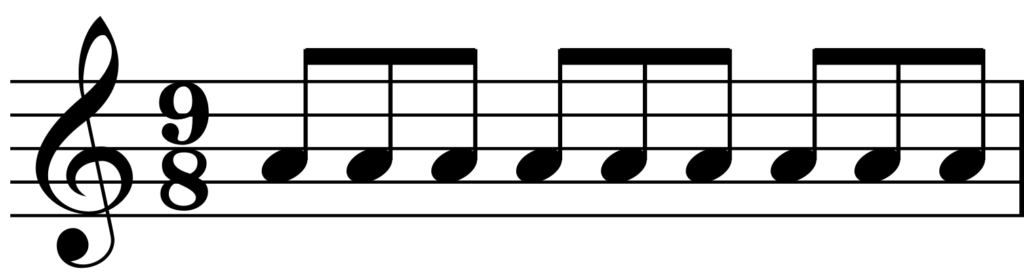

Let’s try another one. In 9/8 time, you know that in every measure there are 9 notes in a 1/8 length.

How about in 4/2 time?

In 4/2 time, each measure has 4 notes of 1/2, so we have 4 1/2 notes:

Now try 3/1 time.

In 3/1 time, so we have 3 notes of a 1/1 length, so 3 whole notes!

Common Time and Cut Time

The above steps are how you figure out the notes and beats of most time signatures, but what about the two time signatures that are letters? As a matter of fact, the two letter time signatures are actually shorthand and variations for the most common numerical time signatures, 4/4 and 2/2.

The 4/4 time signature is so common that it actually has two names and two forms, the first being 4/4, and the second being the ![]() , literally called “Common Time.” So whenever you see the

, literally called “Common Time.” So whenever you see the ![]() in music, you know that it is actually 4/4 time (which has how many notes of what kind of length?).

in music, you know that it is actually 4/4 time (which has how many notes of what kind of length?).

Another prevalent time signature is the ![]() . It looks a lot like the “Common Time” signature, except it has a slash through it. Technically, these measures have four quarter notes in them as well, but this one is called “Cut Time,” hence the C being slashed or “cut.” This “Cut Time” change to “Common Time” means it goes twice as fast, so instead of the quarter note getting the beat, the half note gets the beat! The

. It looks a lot like the “Common Time” signature, except it has a slash through it. Technically, these measures have four quarter notes in them as well, but this one is called “Cut Time,” hence the C being slashed or “cut.” This “Cut Time” change to “Common Time” means it goes twice as fast, so instead of the quarter note getting the beat, the half note gets the beat! The ![]() is like 2/2, just written different and used for faster tempos than 2/2.

is like 2/2, just written different and used for faster tempos than 2/2.

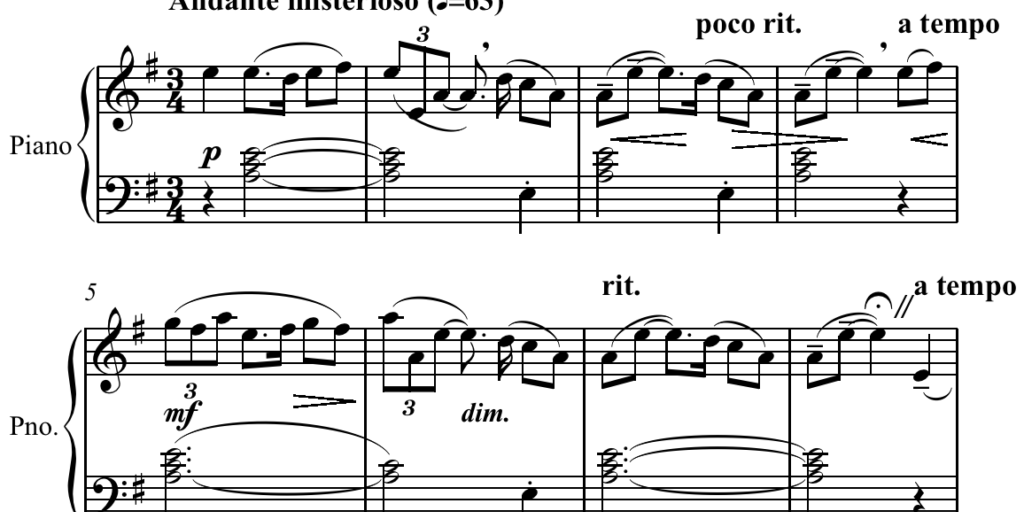

Below is an example from the opening of Edvard Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suite, “In the Hall of the Mountain King.” This excerpt is in marked in Common Time with a big C, which means 4/4. If you count the notes in the measures, you will see that there are four quarter-notes worth of time per measure.

This example is particularly relevant to our discussion of Common and Cut time, because as this piece continues, it gradually increases in speed, moving from sounding like a 4/4 to 2/2. And this is actually what happens! By the end of the piece, the conductor directs the orchestra in Cut Time rather than Common Time. Listen to this performance to hear the beats get faster and see if you can hear when the orchestra switches into Cut Time!

Meter Classifications

We've talking about the basics of reading and deciphering time signatures - now we get to learn how those time signatures can be understood as meters.

There are two levels of classifying meters. The first level of classification focuses on how the beat indicated by the time signature is subdivided.

There are only two ways for the beat to be regularly subdivided in Western music, and that is into two or into three smaller notes. Refer to the note value charts above. All other subdivisions are either multiples of these two subdivisions, or some complex form of adding them together. For ease of notation and classifying the subdivisions as meters then, we have: Simple Time, Compound Time, and Irregular Time.

Simple Time

Simple time is any meter whose basic note division is in groups of two. Examples of these meters include: Common Time, Cut Time, 4/4, 3/4, 2/4, 2/2, 2/1, and so on. These meters are simple time because the quarter note divides equally into two eighth notes, the half-note divides equally into two quarter notes, or the whole note divides equally into two half notes. You can see these divisions if you refer back to the above note length chart.

Compound Time

Slightly more complicated is compound time, which is any meter whose basic note division is into groups of three. You automatically know you are not in simple time if there is an 8 as the bottom number of your time signature. An 8 to mark simple time would be pointless, as will be demonstrated below in the beat hierarchies and accents section.

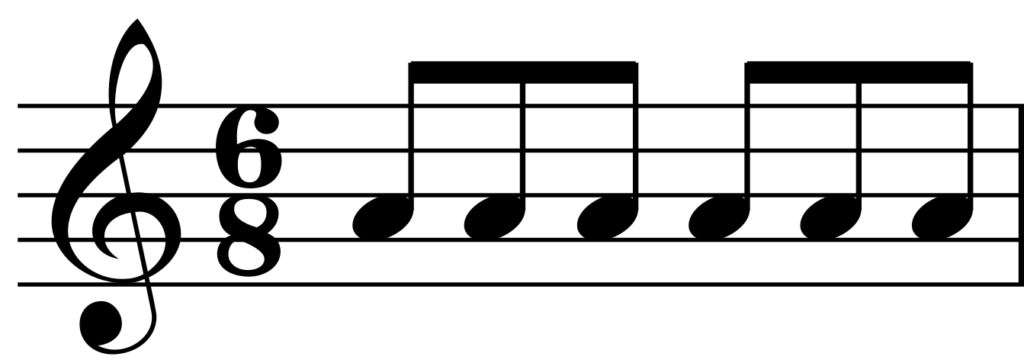

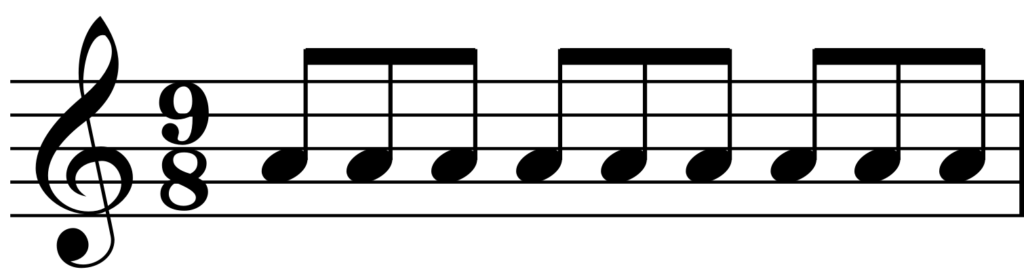

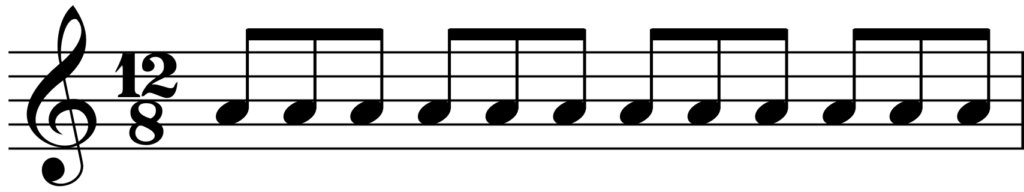

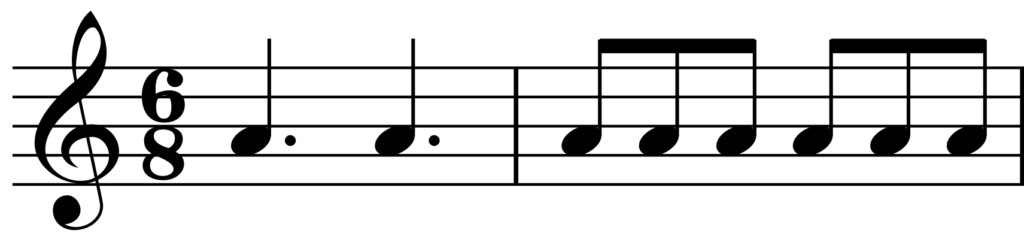

So, when you see an 8 as the bottom number of your time signature, you know that your eighth notes should be grouped together in groups of three instead of two! In 6/8, you have two groups of three eighth-notes, in 9/8 you have three groups of three eighth notes, and 12/8 has four groups of three eighth notes.

Technically, to get a compound time sound, composers could use a simple time signature and then mark all of the main beat subdivisions in triplets - making a duple division into a triple division - throughout an entire piece to get the same effect. However, using triplets throughout an entire piece to get a compound time sound would appear quite messy and cluttered on the page.

An example of the 12/8 against the 4/4 using triplets is in the table below. To the listener, these examples sound exactly the same, and in practice there is the added risk of confusing performers unused to switching between time signatures.

Even though it's more common to see a simple time signature with the duple divisions in Western music for music of the past five or six centuries, it was actually compound time which developed and was notated first! Because Western music notation developed alongside church music, much of the underlying theory surrounding music had a theological basis. For meter, the most common subdivision was in compound or triple divisions to relate musical time being three in one, similar to the Christian Trinity of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.

Irregular Time

The final option for beat subdivision is an irregular or unequal subdivision of the beat.

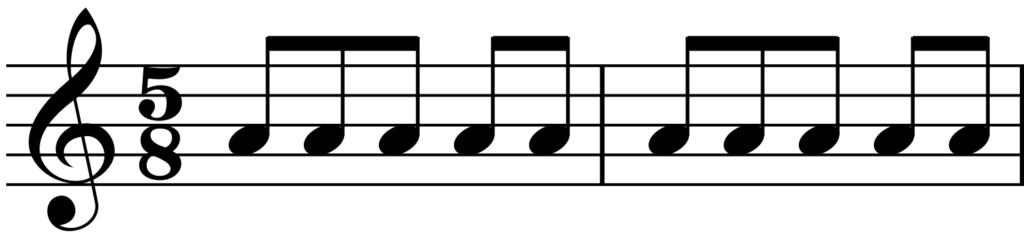

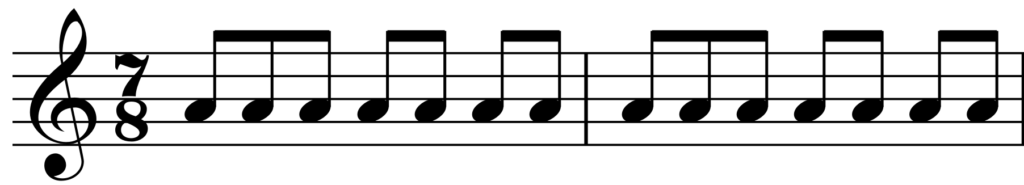

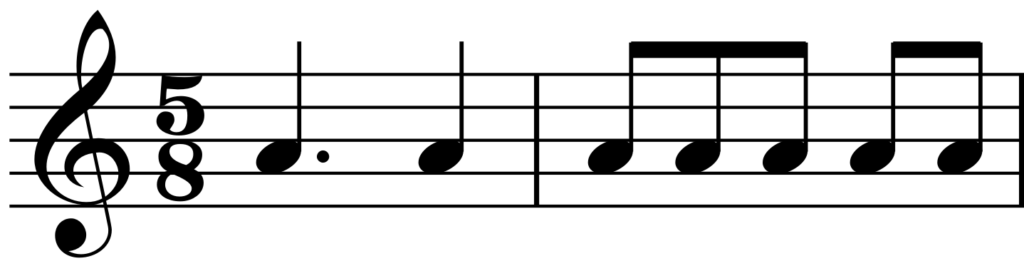

Even though these are “irregular” meters, they do have patterns that are discernable for the performer. The most common irregular meters actually mix simple time and compound time together within a single measure. Thus, in each measure, there are beats with three subdivisions and there are beats with two subdivisions. Examples include such time signatures as 5/8 and 7/8. Because there are 5 eighth notes per measure or 7 eighth notes per measure, you cannot have equal groupings of 2 or 3 eighth notes. Therefore, similarly to 6/8, 9/8, and 12/8, in which the groups of eighth-notes are beamed together to a larger count, in 5/8 and 7/8 they are also beamed together to make a larger count. However, because the number of eighth notes in 5/8 and 7/8 is odd (and prime), the count lengths in each measure are uneven—or irregular. The eighth note typically stays the same length, but because some counts have two and some counts have three eighth notes, they are irregular!

You can see the groupings of three eighth notes with two eighth notes in each measure of 5/8 above, and groups of two eighth notes against two groups of two eighth notes in each measure of 7/8. In 5/8 and 7/8 then, the first count of each measure is one eighth-note longer than the rest of the counts. Depending on where the placement of the longer beat, composers can create different accents and atmospheres.

Russian composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky (1840—1893) uses an irregular meter in the second movement of his Sixth Symphony. When you listen to the movement, it sounds like it should be a waltz with three beats per measure, but the “beats” of the meter are uneven, sometimes the first beat is longer, sometimes it is shorter because the subdivisions are irregular. To the listener, because it sounds like a waltz and like a dance, it feels at once familiar, but then also lopsided and distant. The irregular beat patterns are unexpected and un-danceable (at least without some serious practice and memorization!). The familiar becomes distorted, distant, potentially dangerous and frightening.

Duple, Triple, and Quadruple Classifications

The second level of classification for meters is how many beats there are in a measure. There are three which are the most common: duple (2/2, 2/4, 6/8), triple (3/4, 9/8, 3/2), and quadruple (4/4, 12/8, 4/2). A duple meter has two beats per measure, a triple meter has three beats per measure, and a quadruple meter has four beats per measure. It is rare to see any larger or smaller that are not an equivalent to one of these three.

Cut-Time is duple and simple meter because there are two beats per measure and those beats are divisible by two:

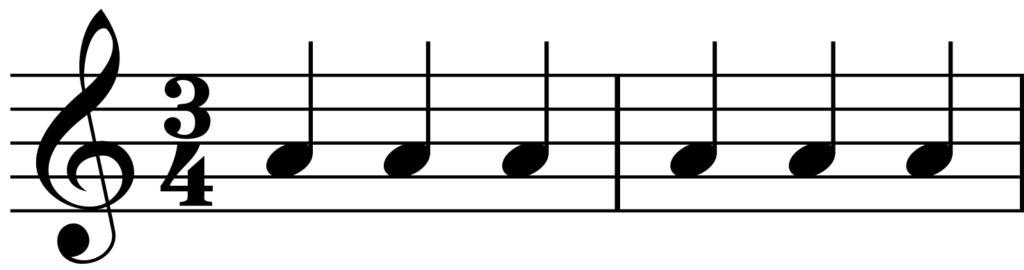

3/4 time is triple and simple meter because there are three beats per measure and each beat is divisible by two:

4/2 is quadruple and simple meter because there are four beats per measure and each beat is divisible by two:

6/8 time is duple and compound meter because there are two beats per measure and each beat is divided into three:

9/8 time is triple and compound meter because there are three beats per measure and each beat is divided into three:

5/8 time is duple and irregular meter because there are two beats per measure and each beat is divided irregularly:

Look through your scores at home: what are some of the meter classifications that you have been playing?

As you can see from the above explanations of the various time signatures and their meters, there are a lot of similarities and subtle nuances between all of these meters. For example, all of the duple and quadruple time meters are similar in that they have two and four beats per measure. This trait makes them sound very similar to the ear.

Depending on the tempo of the piece, triple and simple time pieces can sound compound and some compound pieces (i.e. 6/8) can sound like they have a simple beat subdivision but triple (i.e. the 6/8 sounding like 3/4)! What helps to distinguish a lot of these meters is the beat hierarchies and typical styles of music in which they are employed.

Beat Hierarchies

Music is sound organized through time, and the time signature tells us how to structure that music in time.

Another important piece of information within that time signature is which notes—which beats—are more important and should get accented. This accentuation of beats is known as a “beat hierarchy.” In almost all Western Classical music, the first beat of every measure is the strongest and most important beat, and should carry the most weight. In duple meters then, the second beat is weak and any subdivisions of the beat are weaker still. In quadruple meters, beat three of the measure is actually stronger than beat two, but not quite as strong as beat one, and beat four should lead into the next downbeat (beat one of the next measure). Triple time starts with a strong beat one, has a weak beat two, and then begins to build on beat three (leading to beat one again).

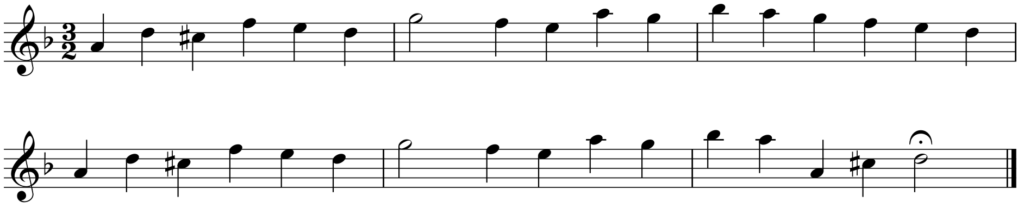

Understanding the beat hierarchies of the different time signatures can help you to interpret repertoire, especially those that use minimal articulation. For example, check out this 3/2 example from the Spirtuoso movement in Telemann’s Fantasia #6 for solo flute:

Because this piece is marked in 3/2 time, it should be in triple and simple time. However, there are no phrase markings and some musicians who have studied Baroque performance practices have argued for sections of this piece being in two instead of three. Switching the meter from a two to three feel is like giving the piece a 6/8 time signature and making the 6/8 eighth note equal to a 3/2 quarter note. With a 6/8 type meter, the Fantasia would be duple and compound, changing the beat hierarchy and accents from every second quarter note to every third quarter note.

Hemiola

The particular Telemann example above, when performed with a changing beat hierarchy, can be an example of a metric and rhythmic technique called hemiola. Hemiola is a two against three subdivision of beats being played against—and right next—to each other.

Syncopation

Another way to disrupt the beat hierarchy of meters in music is to use syncopation. Syncopation is the rhythmic shifting of the accented beat from the traditionally strong beats of one and three. In most cases this is done by a really short note on the downbeat which is immediately followed by an accented long note, or having a tie to an un-articulated downbeat, so that the downbeat gets completely lost. A textbook example of how syncopation can disrupt beat hierarchy can be seen in the ragtime piece “The Entertainer” by Scott Joplin.

From the very first verse, the melody line bounces quickly off the sixteenth-note downbeat onto the accented eighth-note. Then, the next measure’s melody downbeat is tied over from the previous measure. Without the score or the repeated eighth-note chords in the left hand of the piano, you would not know where the downbeats were or be able to track the movement of the measures as easily!

So we have all of these meters and this is how they’re broken down, but… why?

We have all of these different meters and possibilities for subdividing meters to fit the wide variety of music we have! Essentially, different kinds of music require different Simple or Compound time signatures and duple or triple meters. When we connect the music to how it is or was supposed to be used, we find some of the answers to this.

Take a March for example: marches are meant to be, well, marched to, in strict time, and as humans we only have two legs! So out of necessity, marches have to be in a duple or quadruple time. That is why marches are (almost) always in Cut Time, 2/4, 4/4, or on occasion, 6/8. Sousa’s iconic “Stars and Stripes Forever” is in Cut Time. Even though “Stars and Stripes,” and other marches still being composed through today, are rarely still marched to, they are still written in a duple time.

Dance music is another example of music that has to be in a specific meter. Most dances throughout history have had a prescribed number of steps and the music that accompanies the dances must match. For example, waltzes have to be in triple time because they follow a pattern of three steps before repeating the cycle.

The choice of meter and note length provided in the time signature is also a possible indicator of tempo. Generally speaking, one would expect a piece notated in 4/1 to move at a slower tempo than 4/4.

Conclusion

So, that's how you read time signatures! We've investigated how they’re similar and different, how they’re used, and how they can change the music we hear. Many are interchangeable and can sound the same, but have slightly different origins or uses. Meters are how composers organize music through time and communicate that organization to the performers.

For fun, try seeing if you can “play” with any of the meters of your repertoire as if they were in a different meter and tell us about your experiments below!

Learn with LPM

About the Author: Michele Aichele

Michele Aichele is a PhD candidate in Musicology from the University of Iowa, with a MA from the University of Oregon and a BA from Whitman College (Washington). Her interests are in the role of women in composing, performing, teaching, and patronage in music. Her love of learning translates easily to her work with Liberty Park Music. Not only does she get to share her passion for great music and learn from the talented Liberty Park Music teachers, she also gets to help educate more people across the globe through Liberty Park Music’s services.

I’m struggling with understanding signatures and some of the jumps that are made or not explained and it’s doing my head in.

Reading the Time Signatures

9/8 Time, Why are the notes suddenly grouped into threes with no explanation of why?

Common time and cut time.

I get common time (or at least I think I do) but I don’t really understand the explanation of cut time. You say

“Technically, these measures have four quarter notes in them as well … This “Cut Time” change to “Common Time” means it goes twice as fast, so instead of the quarter note getting the beat, the half note gets the beat!” What half note? If its twice as fast won’t they be 1/8 notes?

In the score for the Peer Gynt Suite why are there 1/8 notes went time is 4/4. Are you allowed to have notes of different duration to the one identified in the bottom of the signature? How does that work? Why are they grouped as 4 x 1/8 and then 2 x 1/8. Whats the rule an why is this done.

Dear Steve,

Thank you for reaching out to us with your questions!

As explained later in the article, the eighth notes are grouped in threes instead of twos because 9/8 is a compound time signature. In compound time, each individual beat gets divided into three notes rather than two. The 9/8 eighth notes are grouped in threes to show that all three notes belong to the same beat. In simple time, which includes time signatures like common time and 2/4, the beat is divided into two notes and are thus the eighth notes are grouped in twos and fours in the other examples.

In cut-time, if the eighth note were to get the beat instead of the quarter note, then the music would move twice as slow, as in, you would double the number of beats in each measure—making it twice as long to get through. The rhythms stay the same in proportion to each other, but they go twice as fast. To go twice as fast as the quarter note beat, you would need a beat that fits two quarter notes in length, and that note, based on the diagram in the article, is a half note.

Regarding the Peer Gynt Suite questions, you are allowed to have notes of different duration to the one identified in the bottom of the time signature. The number at the bottom of the time signature simply tells what type of note gets the beat so that the musician knows how to interpret the rhythms of the notes. If you could only have the note-lengths that are indicated by the bottom of the time signature, then there would be no difference in rhythms—no long notes, no short notes, all the notes would have the same duration in every piece.

The eighth notes of the Peer Gynt Suite are grouped in 4 and then 2 because of the time signature. The 4 and 2 groupings reinforce that this time signature is a simple time signature and when you have a series of eighth notes then, you can only group them in groups of four or two. If they were grouped as a group of 6, that would indicate compound time and a different subdivision of the beat. Because we’re going to be going into cut-time with this example, the composer or publisher of the piece grouped the eighth notes to show the emphasis on two “beats” per measure rather than the common time four beats. That is why the first four eighth notes are grouped together—the four eighth notes equal the same length as one half note, which is one beat in cut time. The next two eighth notes are grouped together because they are on the next beat of the measure, but as they are eighth notes, they cannot be barred with the quarter note that follows. And these two eighth notes and the quarter note make up the second beat of the measure.

How do you conduct 1/4 time, I have theory work sheet and am having a hard time understanding how I would draw that.

Hey Laura, it depends on the piece. A good way to start conducting 1/4 would be to try in one beat per measure.

Hi Michele,

How do we distinguish between 3/2 and 6/4?

Thanks for your question Jithin,

The main difference between 3/2 and 6/4 is how you count it. Both time signatures have the same number of quarter notes per measure. In 6/4 you count 6 beats, one for every quarter note. In 3/2 you count 3 beats, one for every half-note.

Many swing band arrangements use the cut time time signature. However, we count off 1,2,1,2,3,4 and play the music as if the time signature was originally in common time or in 4,4. Why is that? The usual answer is “That’s the way it’s always been done.” It’s not a satisfying answer. Any thoughts?

[Response from our drum kit teacher Brendan Bache] This is a really good point. For me cut time, just like common time, is still 4/4. The only difference is the way the beats are felt with the stress on 1 and 3 as opposed to every quarter note pulse. This is often down to the tempo of the piece and when I see cut time in a swing or Latin chart I usually interpret it as 4/4 at a fast tempo.

In short, I’ve always counted it that way, (unless the tempo is so fast that it makes no sense to count quarter notes out loud) partly because that’s what I’ve heard other musicians do but also because I think it makes musical sense.

Thanks for the comment!

thanks for the information

This was a very clear explanation of time signatures. Thank you.

I am naive about music history, and I have a very limited understanding of music theory, but I’ve often wondered how the time signature symbols evolved the way that they did. It seems to me that we have 2 symbols that represent 3 variables (length per base note, base notes per beat, and beats per measure). The 2 symbols provide a compact notation, but is can be more confusing to people who are new to music signatures.

Over the years, has anyone considered time signatures that make all three variables explicit and which have accommodations for uneven time signatures? I was thinking of something like the following:

4/4 time: 4(4𝅘𝅥)

3/4 time: 3(4𝅘𝅥)

6/8 time: 2(3𝅘𝅥𝅮)

9/8 time: 3(3𝅘𝅥𝅮)

5/8 time: 1(3𝅘𝅥𝅮,2𝅘𝅥𝅮)

7/8 time: 1(3𝅘𝅥𝅮,2𝅘𝅥𝅮,2𝅘𝅥𝅮)

Greetings Dennis and thank you for your question! In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, a lot of composers and theorists have come up with more explicit (and less explicit) time signatures to use in their scores. However, each of these is unique to the composer; there is no universal agreement on anything that works better than the current system. Most of the music musicians learn to play use the time signatures explained in the article.

Oops, it should be more like this (I won’t give up my day job):

4/4 time: 4(1𝅘𝅥) or 4(𝅘𝅥) or (𝅘𝅥,𝅘𝅥,𝅘𝅥,𝅘𝅥)

3/4 time: 3(1𝅘𝅥) or 3(𝅘𝅥) or (𝅘𝅥,𝅘𝅥,𝅘𝅥)

6/8 time: 2(3𝅘𝅥𝅮) or (3𝅘𝅥𝅮,3𝅘𝅥𝅮)

9/8 time: 3(3𝅘𝅥𝅮) or (3𝅘𝅥𝅮,3𝅘𝅥𝅮,3𝅘𝅥𝅮)

5/8 time: (3𝅘𝅥𝅮,2𝅘𝅥𝅮)

7/8 time: (3𝅘𝅥𝅮,2𝅘𝅥𝅮,2𝅘𝅥𝅮)

Prior to the 16th century, and the introduction of bar lines, what was the Latin term for the measurement of the length of a beat?

Lyle

Thanks for your question Lyle! I frequently see the beat of pre-16th century music referred to as the “tactus.”

I understand there are no constraints as to what tempo certain meters in a musical piece can be played (if composer decides two measures of 4/4 be played at 120bpm and next 3 measures of 4/4 at 140bpm),but how do we calculate a new tempo to have a different meter “sound/feel” the same. For example we start with 7/8 (has 3 beats, 7 8th notes) at 130bpm moving into 4/4 (4 beats, eight 8ths for the purpose of common denominator) how to get the tempo for 4/4 part? Should we look at beats ratio 3 to 4 or notes ratio 7 to 8? I’ve seen a formula like this but don’t know if it’s right, new tempo=number of notes in new tempo X old tempo / num of notes in old tempo. So in our case 8×130/7=114bpm rounded up

Hi Arek,

I’m not sure quite what you’re asking. It depends on if the composer wants the overall beat to stay the same or keep the length of the eighth-notes or quarter-notes the same. If the beat stays the same, then moving from 4/4 to 6/8 would mean that instead of dividing each beat into two, you would divide it into three, so the subdivisions get faster, but the length of the beat would stay exactly the same. The same would go for 7/8. I imagine your formula would work if the composer wanted the eighth-notes to stay the same.

Hey Steve. Very insightful article. I understand that 2/4 as a simple quadruple time has a different feel from 6/8. I also know that 6/8 can be re-written as 2/4 without the song losing its feel.

Does it mean that the aural feel of 2/4 time signature is always the same as 6/8?

Thanks for your question Jones! No, the aural feel of a 6/8 time signature will not always feel the same as 2/4. It can depend on the tempo. Sometimes it will feel the same, but sometimes, the 6/8 can be stretched out, for example, in some Baroque dance suites.

Wow.. I am indeed blessed with alot of techniques and knowledge on time or measure signature here. Thanks to libertyparkmisic

Michele,

Thanks for the most comprehensive and clear explanation of the time signatures I have ever read, and I think I’ve read all of them. I think I get it now.

As a nubie bass player, getting time and emphasis under control is one of my biggest challenges. This is exasperated by picking Money by Pink Floyd as a piece to show off to my mates.

During this bass line the time switches from 7/4 to 3/4 to 5/4 to 3/4 back to 7/4 and, just for irony I suspect, ends in 4/4 for a couple of bars. It’s a beautiful mess.

(Yes, various recording have whole ‘bridge?’ sections in 4/4 included, I know)

I learned to play it by listening to the recordings, but now that I have read your article, I can follow the score, and tell my guitar playing mates that ‘I KNOW how it goes’.

Thanks for your great work.

Thanks, makes bit more sense now

It will be tomorrow… actually today now, before my subconscious parses this and returns a verdict. My misinterpretation that bars or measures were finite and restricted has been delightfully dismantled. As a singer-songwriter who breathes music I never paid attention to the signature of my breathing. Now, confronting a world of DAW, I need the software to understand my timing, so it can follow and respond well. Today, I learned what a hole, half, quarter and eighth note looks like. As I reverse engineer my fifty+ creations, perhaps soon theory and music will meet and play nice together, so I can record and perform with more weapons in my arsenal. But in three minutes it will be 2am and my brain is full. Thank you

how tempo marking note value is found in irregular meters? ones like 5/4 and 7/8.